Sink your teeth into saving a life

By Eva Grayzel

At the age of 33, performance artist and story teller Eva Grayzel was diagnosed with stage IV oral cancer (squamous cell carcinoma) on the left side of her tongue. Eva ate well, exercised regularly, and had none of the risk factors commonly associated with oral cancer. She was a non-drinker who had never smoked. She was also the mother of two small children, Elena and Jeremy, ages five and seven. Nearly three years earlier, Eva had noticed a sore on the left side of her tongue. She consulted an oral surgeon who removed the sore and had the tissue biopsied. He assured her that the results of the biopsy were negative and told her there was nothing to worry about.Two years passed with no more obvious symptoms. Then a new sore appeared right over the area where the first one had been removed. She visited her dentist and oral surgeon numerous times over the following nine months and, as the sore on the side of her tongue got bigger, both of them continually told her to come back if it didn’t improve. Eva says, “They were asking me to determine whether or not my condition was improving, even though, in living with it every day, the changes were very subtle.”Almost three years passed from the time she initially consulted dental professionals about the sore on her tongue before her condition was accurately diagnosed. Ultimately, she had to endure a partial tongue reconstruction, a modified radical neck dissection, and the maximum dose of radiation therapy. Following her exceptional recovery, she became a motivational speaker, giving presentations on how to find strength from adversity and telling her remarkable story to dental professionals.Neither her dentist nor the oral surgeon ever mentioned the possibility of oral cancer. If they had, she would have been more proactive as the sore became more and more painful. Eight months after the sore on her tongue reappeared, she developed an unbearable earache and was treated for what was diagnosed as “water on the eardrum.” After ten days on antibiotics, she was waking up throughout the nights in tears and she returned to the oral surgeon, desperate for answers. He said, “Your tongue is small and we don’t want to cut it up unless we have to, but at this point, I guess the next step would be another biopsy.”Finally, after nine months of consultations with her dentist and two different oral surgeons, she decided she needed to look elsewhere for answers. A family friend recommended that she see Dr. Mark Urken, chief of head and neck surgery at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City.When she made the two-hour bus trip from Easton, Pennsylvania, into New York City on the day of her appointment, she had no inkling that the nasty sore on her tongue could be cancer. Dr. Urken felt the enlarged lymph nodes in her neck, looked at the classic ulceration on the side of her tongue, and told her that he wanted to do a minimally invasive second biopsy. When the results came back, Dr. Urken told her in a gentle voice that she had a squamous cell carcinoma. Woozy from anesthesia, she asked if it was benign or malignant. In an apologetic tone, he said: “Eva, you are in an advanced stage of oral cancer.” The date was the first of April 1998 and, as Eva says, “It was the cruelest April Fool’s joke of my life.”Surgery and Radiation

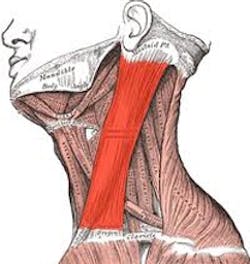

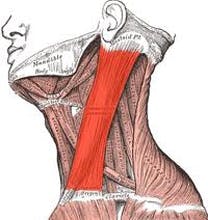

Eva went into shock. Her treatment would consist of a modified radical neck dissection, a partial glossectomy (tongue reconstruction), and the maximum dose of radiation. She was given a 15 percent chance of surviving for more than five years.The surgeon removed and reconstructed one-third of her tongue. Fortunately, he left the tip of her tongue intact so that she would still be able to speak articulately. He took an artery from her left arm to feed blood to the tongue graft and transplanted tissue from her forearm to reconstruct the outside of her tongue. He used grafts from her left thigh to replace her forearm skin and rebuild the tongue’s density. He also removed all of the lymph nodes on the left side of her neck and, ultimately, the entire sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle.

At the age of 33, performance artist and story teller Eva Grayzel was diagnosed with stage IV oral cancer (squamous cell carcinoma) on the left side of her tongue. Eva ate well, exercised regularly, and had none of the risk factors commonly associated with oral cancer. She was a non-drinker who had never smoked. She was also the mother of two small children, Elena and Jeremy, ages five and seven. Nearly three years earlier, Eva had noticed a sore on the left side of her tongue. She consulted an oral surgeon who removed the sore and had the tissue biopsied. He assured her that the results of the biopsy were negative and told her there was nothing to worry about.Two years passed with no more obvious symptoms. Then a new sore appeared right over the area where the first one had been removed. She visited her dentist and oral surgeon numerous times over the following nine months and, as the sore on the side of her tongue got bigger, both of them continually told her to come back if it didn’t improve. Eva says, “They were asking me to determine whether or not my condition was improving, even though, in living with it every day, the changes were very subtle.”Almost three years passed from the time she initially consulted dental professionals about the sore on her tongue before her condition was accurately diagnosed. Ultimately, she had to endure a partial tongue reconstruction, a modified radical neck dissection, and the maximum dose of radiation therapy. Following her exceptional recovery, she became a motivational speaker, giving presentations on how to find strength from adversity and telling her remarkable story to dental professionals.Neither her dentist nor the oral surgeon ever mentioned the possibility of oral cancer. If they had, she would have been more proactive as the sore became more and more painful. Eight months after the sore on her tongue reappeared, she developed an unbearable earache and was treated for what was diagnosed as “water on the eardrum.” After ten days on antibiotics, she was waking up throughout the nights in tears and she returned to the oral surgeon, desperate for answers. He said, “Your tongue is small and we don’t want to cut it up unless we have to, but at this point, I guess the next step would be another biopsy.”Finally, after nine months of consultations with her dentist and two different oral surgeons, she decided she needed to look elsewhere for answers. A family friend recommended that she see Dr. Mark Urken, chief of head and neck surgery at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City.When she made the two-hour bus trip from Easton, Pennsylvania, into New York City on the day of her appointment, she had no inkling that the nasty sore on her tongue could be cancer. Dr. Urken felt the enlarged lymph nodes in her neck, looked at the classic ulceration on the side of her tongue, and told her that he wanted to do a minimally invasive second biopsy. When the results came back, Dr. Urken told her in a gentle voice that she had a squamous cell carcinoma. Woozy from anesthesia, she asked if it was benign or malignant. In an apologetic tone, he said: “Eva, you are in an advanced stage of oral cancer.” The date was the first of April 1998 and, as Eva says, “It was the cruelest April Fool’s joke of my life.”Surgery and Radiation

Eva went into shock. Her treatment would consist of a modified radical neck dissection, a partial glossectomy (tongue reconstruction), and the maximum dose of radiation. She was given a 15 percent chance of surviving for more than five years.The surgeon removed and reconstructed one-third of her tongue. Fortunately, he left the tip of her tongue intact so that she would still be able to speak articulately. He took an artery from her left arm to feed blood to the tongue graft and transplanted tissue from her forearm to reconstruct the outside of her tongue. He used grafts from her left thigh to replace her forearm skin and rebuild the tongue’s density. He also removed all of the lymph nodes on the left side of her neck and, ultimately, the entire sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle.

Radiation therapy began eight weeks after surgery. She found a radiation oncologist in nearby Allentown, Pennsylvania, who had an Intensive Modulation Radiation Therapy (IMRT) machine, which allowed him better control of the radiation exposure to different areas of her mouth and neck. Radiation treatments were twenty minutes long five days a week for six weeks.After two weeks of radiation, the side effects became almost unbearable. Blisters in her mouth and throat resulted in severe pain when swallowing, so eating became extremely difficult. It would take her an hour to eat three spoonfuls of food. She lost her ability to speak as her tongue and vocal chords stiffened. Her saliva became gluey and sticky, causing coughing and breathing difficulties that made it impossible to sleep.Whenever she thought it couldn’t get any worse—it did. At one point, her epiglottis dried up and stopped functioning. Saliva from the back of her throat would drip into her trachea, triggering severe coughing fits that irritated the blisters causing some of them to open and bleed. She was utterly exhausted and came very close to giving up. She wrote final messages to her husband and her children and told her doctor that she wanted to stop her treatments. He convinced her to go on. It took two weeks after radiation ended before the symptoms subsided and the sores started to heal.The winter after radiation, she had hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBO) for an extremely painful split lip that would not heal. Her radiation oncologist prescribed 28 treatments to heal her lip and increase blood circulation to avoid future complications. HBO treatments were several hours long, five days a week, for almost six weeks.Dental Complications

Six years later, she had to have a molar extracted on the only side of her mouth where she is able to chew. She saw a specialist in New York who had experience treating oral cancer patients. After the extraction, she was in pain for a month. She begged her doctor for more HBO since nothing else worked. He told her that the 28 treatments she had done six years earlier would last a lifetime. She complained so much that he finally agreed to prescribe ten more treatments, and after just two treatments the pain was eradicated.Three years later, she had the adjacent lower molar extracted, after which she had difficulty chewing and started to lose weight. She explored the options. Her dentist did not recommend a bridge spanning two molars, and an oral surgeon specializing in irradiated bone, strongly discouraged using dental implants because the risk of osteoradionecrosis (ORN) was too great. However, a specialist in oncologic dentistry told her that implants might work. Bone that isn’t stimulated results in continued bone loss and leaves no chance for future implants. He was confident from the results of a cone-beam X-ray that her bone was sufficiently dense. Luckily, all three of the implants she had were successful.Neck Problems

After the initial cancer surgery her head drooped to the left and she couldn’t straighten it because the left SCM had been removed. She found a myofacial, neuromuscular therapist, who gently worked to release scar tissue adhesions in her neck so she was finally able to hold her head up. She credits much of her current range of motion to those regular neck treatments. She must push her head up with her hand when getting out of bed, she has to catch her head whenever the car stops suddenly, and must support her head when leaning back. She gets a cramp in her neck when she shaves under her arms and experiences severe itching along the length of her neck scar when she eats anything remotely spicy. She has adapted to all these changes without much problem.Dry Mouth and Oral Hygiene

Unfortunately, dry mouth is a condition that is more complicated. Immediately following radiation treatments, her mouth was so dry that she had to practically pry her mouth open to moisten it with water. Over the years, her saliva production has increased and she can make it through some nights without drinking if she sleeps with her mouth closed. It is quite a challenge, but it is possible.Even though she only chews on her right side, the left side of her mouth gets grimier from the lack of saliva. Before she goes to bed, she brushes, flosses, stimulates, uses a proxy brush, irrigates, and finishes off with Prevident , a fluoride treatment.Tongue Issues

Her surgeon had hoped that she would regain feeling on the grafted side of her tongue, but she has not. Eva says, “It feels just like a tongue that has been shot with Novocaine.” Initially, the graft on the tongue was very white, since it came from the inside of her wrist, the palest skin on her body. When she talked, it would look like she had a big wad of gum on that side. Over time, however, the grafted area has adapted to its environment and the color has changed from white to pink—a welcome improvement in the interior design.Importance of Early Diagnosis

If Eva’s cancer had been diagnosed early, it would have been about seven days from surgery to recovery. Instead, seven months of her life passed during her initial surgery, radiation treatment, and recovery. Also, her children were traumatized by her surgery and ongoing treatment. They could barely look at her when she came home from the hospital, and shied away from her touch fearing that she was contagious. Her ordeal continues with a lifetime of dental complications, numerous doctor’s appointments and diagnostic tests, health scares, occasional ringing in her ears, sensitivity to sunlight in her eyes, and other quality-of-life compromises.During the 13 years since her diagnosis, she has had three negative biopsies and bilateral vocal cord polyps, but no recurrence of cancer. She will have to take Synthroid for the rest of her life to counteract the effects of compromised thyroid function from the radiation.Now, as she tells her story professionally, she says, “It is more than a mission to educate. It’s my tribute to those who came before me and my obligation to those who will follow. During radiation, when I was teetering on the tightrope between life and death, I thought good and hard about how I would be remembered. I would not be remembered for taking my children to ballet and soccer, but for how I made a difference in other people’s lives. If you can save one life in your entire career by performing oral cancer screenings on everyone and detecting it early, wouldn’t it be worth it?”

Six years later, she had to have a molar extracted on the only side of her mouth where she is able to chew. She saw a specialist in New York who had experience treating oral cancer patients. After the extraction, she was in pain for a month. She begged her doctor for more HBO since nothing else worked. He told her that the 28 treatments she had done six years earlier would last a lifetime. She complained so much that he finally agreed to prescribe ten more treatments, and after just two treatments the pain was eradicated.Three years later, she had the adjacent lower molar extracted, after which she had difficulty chewing and started to lose weight. She explored the options. Her dentist did not recommend a bridge spanning two molars, and an oral surgeon specializing in irradiated bone, strongly discouraged using dental implants because the risk of osteoradionecrosis (ORN) was too great. However, a specialist in oncologic dentistry told her that implants might work. Bone that isn’t stimulated results in continued bone loss and leaves no chance for future implants. He was confident from the results of a cone-beam X-ray that her bone was sufficiently dense. Luckily, all three of the implants she had were successful.Neck Problems

After the initial cancer surgery her head drooped to the left and she couldn’t straighten it because the left SCM had been removed. She found a myofacial, neuromuscular therapist, who gently worked to release scar tissue adhesions in her neck so she was finally able to hold her head up. She credits much of her current range of motion to those regular neck treatments. She must push her head up with her hand when getting out of bed, she has to catch her head whenever the car stops suddenly, and must support her head when leaning back. She gets a cramp in her neck when she shaves under her arms and experiences severe itching along the length of her neck scar when she eats anything remotely spicy. She has adapted to all these changes without much problem.Dry Mouth and Oral Hygiene

Unfortunately, dry mouth is a condition that is more complicated. Immediately following radiation treatments, her mouth was so dry that she had to practically pry her mouth open to moisten it with water. Over the years, her saliva production has increased and she can make it through some nights without drinking if she sleeps with her mouth closed. It is quite a challenge, but it is possible.Even though she only chews on her right side, the left side of her mouth gets grimier from the lack of saliva. Before she goes to bed, she brushes, flosses, stimulates, uses a proxy brush, irrigates, and finishes off with Prevident , a fluoride treatment.Tongue Issues

Her surgeon had hoped that she would regain feeling on the grafted side of her tongue, but she has not. Eva says, “It feels just like a tongue that has been shot with Novocaine.” Initially, the graft on the tongue was very white, since it came from the inside of her wrist, the palest skin on her body. When she talked, it would look like she had a big wad of gum on that side. Over time, however, the grafted area has adapted to its environment and the color has changed from white to pink—a welcome improvement in the interior design.Importance of Early Diagnosis

If Eva’s cancer had been diagnosed early, it would have been about seven days from surgery to recovery. Instead, seven months of her life passed during her initial surgery, radiation treatment, and recovery. Also, her children were traumatized by her surgery and ongoing treatment. They could barely look at her when she came home from the hospital, and shied away from her touch fearing that she was contagious. Her ordeal continues with a lifetime of dental complications, numerous doctor’s appointments and diagnostic tests, health scares, occasional ringing in her ears, sensitivity to sunlight in her eyes, and other quality-of-life compromises.During the 13 years since her diagnosis, she has had three negative biopsies and bilateral vocal cord polyps, but no recurrence of cancer. She will have to take Synthroid for the rest of her life to counteract the effects of compromised thyroid function from the radiation.Now, as she tells her story professionally, she says, “It is more than a mission to educate. It’s my tribute to those who came before me and my obligation to those who will follow. During radiation, when I was teetering on the tightrope between life and death, I thought good and hard about how I would be remembered. I would not be remembered for taking my children to ballet and soccer, but for how I made a difference in other people’s lives. If you can save one life in your entire career by performing oral cancer screenings on everyone and detecting it early, wouldn’t it be worth it?”

Eva’s career as an interactive performance artist and master storyteller allow her to communicate her experience as a patient and survivor in a unique and powerful way. For ten years, Eva has been telling her intimate and dramatic story of surviving late-stage oral cancer at dental meetings and dental schools. A champion for early detection, Eva developed an oral cancer awareness campaign, Six-Step Screening, for which she was recognized by the American Academy of Oral Medicine. She is the author of ‘You Are Not Alone: Families Touched by Cancer.’