Mouthguard evolution

More athletes mean more mouthguard opportunities for dental professionals

By Dan Brett, DDS

As athletic participation continues to increase in the United States, the need for athletic mouthguards will continue to climb as well. Approximately 20 million children participate in sports programs, and another 80 million are involved in unsupervised recreational sports. Some estimate there are 40 million mouthguards sold in the United States each year. With many states taking the initiative to make mouthguards mandatory for what have been traditionally classified as "non-contact sports" such as basketball, soccer, and wrestling, the need for athletic mouthguards may very well double.

Unfortunately, custom-fitted mouthguards fabricated by dental professionals represent only about 2 to 4 percent of the mouthguard market. These numbers are in sharp contrast to the 71 percent of all dentists who routinely recommend mouthguards for their athletically active patients. Two factors contribute to this disparity — the lack of academic training that dentists receive in sports dentistry, and the cost associated with a professionally made, custom-fit athletic mouthguard when compared to those bought over the counter at the drug or sporting goods store.

This article will discuss some of the new technology available in custom-fitted mouthguard fabrication and provide step-by-step instructions for fabricating a multi-laminated mouthguard featuring PolyShoK™ material and vacuum pressure.

In the early to mid-1990s, the technology of fabricating high-heat and pressure-laminated mouthguards was introduced in the U.S. By using processing equipment that formed ethyl vinyl acetate (EVA) dental plastic with positive pressure at about 90 psi (as opposed to about 12 psi for vacuum pressure), greater details to the hard and soft tissues were achieved, resulting in a better-fitting mouthguard. A further advantage of this technique is the ability to laminate or fuse a second or third piece of EVA in a separate processing cycle over the first layer.

Some studies suggest that, by fabricating a multi-laminated mouthguard with an interoclussal thickness of between 3 to 5 millimeters, there is a reduction in the rate of concussion received by a blow to the mandible. This desired thickness typically can't be achieved by vacuum-forming a single sheet of EVA because the material loses approximately 50 percent of its original thickness as it softens and droops. Therefore, if you start with a piece of 4-millimeter EVA, the resulting mouthguard will measure approximately 2 millimeters, making it fall outside of the 3 to 5 millimeter range. Also, with the low-forming pressure of a vacuum, it is difficult to achieve complete lamination of two layers of EVA dental plastics.

While there have been advancements made in mouthguard-fabrication processing equipment, there has not been a significant improvement in mouthguard materials until recently. EVA plastics have been used for mouthguard fabrication for decades. Even though it has a few favorable characteristics — namely the ability to form at low temperatures and cost — it is not considered a very shock-absorbent material. By developing a material that has increased shock absorption (energy absorption), it should translate into a material that transfers less force to the teeth and supporting structures.

One of the first significant changes in mouthguard materials has occurred with the development of PolyShoK™ mouthguard material. This EVA-based co-polymer has been ASTM-tested (D3763) to be between 152 and 285 percent more shock-absorbent than standard EVA mouthguard materials. It is a softer material than EVA — Shore A hardness of 78 compared to 80 — which results in a more comfortable mouthguard.

Outside of its higher shock-absorption properties, its greatest attribute may be that it can be laminated to itself using vacuum pressure. As previously stated, there seems to be some advantage in protection by offering a mouthguard to athletes that has an interoclussal thickness of 3 to 5 millimeters. This can now be achieved by laminating PolyShoK™ in two different forming cycles as detailed in the following fabrication technique. Although the internal adaptation of the mouthguard is not as precise as high heat and pressure processing equipment, this technique allows you fabricate a mouthguard with increased thickness using a vacuum-form machine, which cost several times less than pressure laminating machines.

To determine the final thickness of your multi-layer mouthguard, a good rule of thumb is to calculate the thinning of the material in processing at 50 percent. For instance, if you wanted to fabricate a mouthguard with the final thickness of 3 to 3.5 millimeters, you would need a total of two layers that had a combined thickness equaling 6 millimeters. You could process a first layer of 3-millimeter sheet of PolyShoK™ followed by another 3-millimeter sheet or a first layer of 4 millimeter followed by a 2-millimeter sheet.

Making a mouthguard

Note: Two colors of material were used for demonstration purposes.

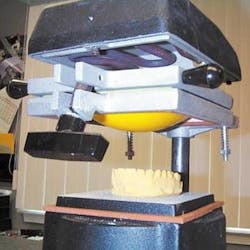

Step 1: Clamp PolyShoK™ material between top and bottom plates of the vacuum former.

null

Step 2: Move material into proper position and center model on the vacuum plate. Turn on heating element and allow material to heat and droop approximately 1 to 2 inches.

null

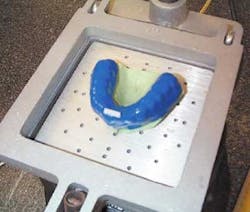

Step 3: Turn on vacuum. Using handles, pull material down over model. Let vacuum run for at least 30 seconds. Let material cool.

null

Step 4: Trim first layer. Clamp a second sheet of PolyShoK™ material, heat and repeat vacuum process.

null

Step 5: Let material cool. Remove from model. Trim second layer around same outline as first layer.

null

Step 6: Fine-trim your mouthguard. Finish and polish as desired.

null

Dan Brett, DDS, is president of Sportsguard Laboratories, Inc., a leader in custom mouthguard fabrication. PolyShoK was engineered to absorb more energy than EVA mouthguard materials, thus transmitting less force to dental structures. Sportsguard Laboratories, Inc. is located at 5960 Horning Rd., Kent, Ohio, 44240 and can be reached at (800) 401-1776.

Adding a strap to a PolyShoK™ mouthguard

Step 1: After the first layer is formed and trimmed, using a glue gun, place a small amount of glue centered over the upper front teeth.

null

Step 2: Place a piece of heavy monofilament line or wooden dowel (.130 inch in diameter) on glue centered over the upper front teeth.

null

Step 3: After laminating and trimming a second layer, cut the material covering the ends of the dowel and push dowel out, creating a channel.

null

Step 4: Thread Tygon tubing (1/8 O.D., 1/16 I.D.) through channel created by dowel.

null

Step 5: Use (0.65 diameter) monofilament to attach open ends of the tubing.

null

Step 6: Wrap athletic tape to secure the seam and create a loop.

null