Understanding Acid Reflux and Its Dental Manifestations

A Peer-Reviewed Publication

Educational Objectives

After taking this course the reader should be able to

- define acid reflux and describe the clinical signs and symptoms,

- identify and explain medications used in the treatment of acid reflux from a patient’s health history,

- list the dental implications associated with acid reflux, and

- recommend dental therapies to protect the oral health of patients suffering from acid reflux.

Introduction

Dental professionals commonly review health histories listing medications that identify patients with a diagnosis of acid reflux. Most often, a specialized physician known as a gastroenterologist treats this condition. However, there are dental manifestations, so it is important that dental professionals identify these patients and recommend appropriate dental therapies to protect the long-term health of the dentition. Furthermore, dental professionals have the opportunity to recognize this condition in untreated patients and may need to refer those patients to a physician for further evaluation.

Overview

Evidence indicates that up to 36 percent of otherwise healthy Americans suffer from heartburn at least once a month and that 7 percent experience heartburn as often as once a day. The incidence of GERD increases markedly after the age of 40. Not just adults are affected; even infants and children can have GERD.

Pathogenesis: Mechanism of Reflux

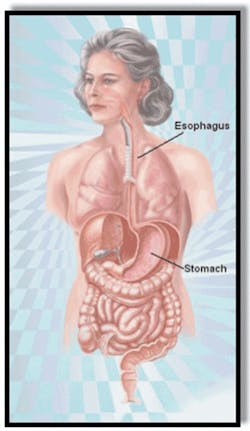

The stomach produces hydrochloric acid after a meal to aid in the digestion of food.

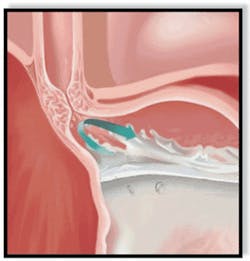

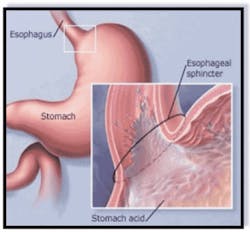

Normally, a ring of muscle tissue called the lower esophageal sphincter, which is located in the lower portion of the esophagus where it joins the stomach (esophagogastric junction), prevents reflux (or backing up) of acid from the stomach (Figures 2--3).

This sphincter relaxes during swallowing to allow food to pass. It then tightens to prevent flow in the opposite direction.

With GERD, however, the sphincter relaxes between swallows, allowing stomach contents and corrosive acid to well up and damage the lining of the esophagus (Figure 4).

Etiology

GERD is caused by a combination of conditions that increase the presence of acid reflux in the esophagus. Factors that weaken or relax the lower esophageal sphincter make reflux worse are:

- Lifestyle -- Use of alcohol or cigarettes, obesity, and poor posture (slouching).

- Medications -- Calcium channel blockers, beta blockers, theophylline (Tedral, Hydrophed, Marax, Quibron), nitrates, and antihistamines.

- Diet -- Fatty and fried foods, chocolate, garlic and onions, drinks with caffeine, acidic foods such as citrus fruits and tomatoes, spicy foods, and mint flavorings.

- Eating habits -- Eating large meals and/or eating just before bedtime.

- Other medical conditions -- Hiatal hernia, pregnancy, diabetes, and rapid weight gain.

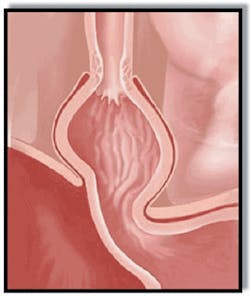

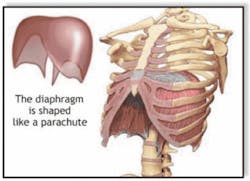

Another well-described condition associated with GERD is hiatal hernia (Figure 5). It is defined as the protrusion of the upper part of the stomach above the diaphragm (a thin, dome-shaped muscle that separates the thoracic cavity (lungs and heart) from the abdominal cavity (intestines, stomach, liver, etc.)). (See Figure 6)

- Normally, the diaphragm acts as an additional barrier, helping the lower esophageal sphincter keep acid from backing up into the esophagus.

- A hiatal hernia distorts the lower esophageal sphincter, impairing its function and making it easier for the acid to back up.

- Hiatal hernias can be caused by persistent coughing, vomiting, straining, or sudden physical exertion. Obesity and pregnancy can make the condition worse.

- Hiatal hernias are very common in people older than 50.

- Hiatal hernia usually requires no treatment. In rare cases when the hernia becomes twisted or is making GERD worse, surgery may be required.

CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS AND NATURAL HISTORY

Typical Symptoms

The common symptoms of GERD are heartburn, acid regurgitation, and difficulty swallowing (dysphagia).

Persistent heartburn, sometimes referred to as acid indigestion, is the most common symptom of GERD.

- Heartburn is a burning, painful sensation in the center of the chest, behind the sternum (breastbone). It often starts in the upper abdomen and spreads up into the neck.

- It is usually worse after eating and can last as long as two hours.

- The pain usually does not start or get worse with physical activity.

- Exacerbating factors include lying down or bending over.

- The absence of heartburn does not rule out GERD.

Acid regurgitation is defined as the effortless return of esophageal or gastric contents into the pharynx without nausea or retching. Patients note the presence of a sour or burning fluid in the throat or mouth that may also contain undigested food particles.

Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) is reported by more than 30 percent of individuals with GERD. It is usually the result of strictures (see Disease Course).

Atypical Symptoms

Atypical symptoms include the following:

- Posterior laryngitis:

Acid reflux can cause laryngeal mucosal breakdown. A common symptom is hoarseness due to vocal cord injury by the acid. - Respiratory symptoms:

Acid reflux into the respiratory tree can cause asthma-like symptoms in the form of wheezing. In addition, it can also cause chronic nonproductive cough. - Noncardiac chest pain:

It is estimated that 65 to 75 percent of patients with noncardiac chest pain have GERD as the potential etiology of their symptoms. - Dental manifestations:

Acid reflux is associated with a

demineralization action resulting in dental enamel erosion (Figure 7).

Dental enamel consists primarily (almost 97 percent by weight) of a calcium phosphate mineral in the form of carbonated hydroxyapatite (CHA). CHA is insoluble in an alkaline medium. However, its solubility increases with a decrease in the oral pH. This effect was first noted as a result of direct contact of the tooth surface with acids from extrinsic sources such as beverages. Unlike dental caries, where the demineralization is caused by an acidic environment in GERD is due to the reflux of hydrochloric acid from the stomach (Figure 8.).

The erroseive effect tends to be locoalized on the palatal aspects of the maxillary teeth. The dental enamel erosion has been documented by profilometric scans, spectrophotometric analysis, and scanning electron microscopy(SEM).

Patients on some weight loss diets and those who consume fruit based drinks are at an increased risk due to the additional extrinsic exposure of acid contained in these diets.

Psychiatric disorders such as bulimia nervosa, where patients eat excessively and then induce vomiting several times, is another intrinsic source of oral acid. The vomiting of gastric content serves as the source of the acid. Salivary function is important in neutralizing the acid refluxing from the stomach and hence reducing its dental erosive effect. Medications that reduce the salivary function contribute to the acid-induced dental erosion problem. These medications include antidepressants, antipsychotic medications, bronchodilators, and diuretics. The progressive steps of erosion as reported by Pontefract are as follows:

- Chalky or “frosted” appearance

- Smooth, glazed appearance

- Eroded and thinned enamel with pitted microcracks and a translucent appearance

- Cupping of cusp edges of posterior teeth

- Flat occlusal surfaces

Disease Course

GERD patients typically report having had symptoms for one to three years prior to seeking medical attention. Due to the esophageal lining inflammation resulting from GERD or failure to treat or identify GERD can predispose patients to complications including the following:

Most patients respond to therapy. As a result, early consideration of GERD in the differential diagnosis and consequent initiation of therapy is the most important aspect of GERD management.

Approach to the Diagnosis

Typical symptoms are usually sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of GERD and to initiate appropriate treatment. However, in GERD patients with atypical symptoms, diagnostic studies are required to confirm that abnormal acid reflux is occurring and is potentially responsible for the symptoms in question.

One approach to diagnosis involves an empirical trial with medications that inhibit hydrochloric acid production (antisecretory therapy). Medical response confirms the diagnosis and defines patients as good candidates for antisecretory therapy (most patients are in this category).

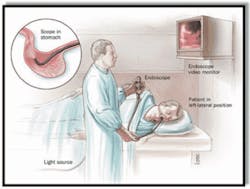

The other diagnostic tools usually performed by a gastroenterologist include an upper GI endoscopy, also called esophagogastroduodenoscopy or EGD; esophageal manometry; and 24-hour pH study.

Upper GI endoscopy or EGD is a procedure that is performed at the gastroenterologist’s office (Figure 9).

It allows the specialist to make diagnoses, assess damage, take biopsies if necessary, and even treat certain conditions on the spot. It involves sedation followed by the introduction of a flexible probe with a tiny camera on the end through the mouth to the first part of the small intestine (duodenum). The camera allows for the appropriate assessment of esophageal damage caused by GERD. An apparently normal esophagus does not rule out the diagnosis. This can be seen in the context of mild GERD.

Esophageal manometry is a test that measures the function of the lower esophageal sphincter and the motor function of the esophagus. A tube is passed down the patient’s throat until it reaches the lower esophageal sphincter. It is often performed along with a 24-hour pH probe study.

A 24-hour pH probe study is a test during which a thin tube is placed down into the esophagus for 24 hours. The tube monitors episodes of acid reflux over the day and overnight during sleep. A wireless pH system is available. This system involves the deployment of a probe in the esophagus (the Bravo procedure) that measures the pH and sends the measurements to a device carried by the patient.

Treatment

The goals of treatment are reducing reflux, relieving symptoms, and preventing damage to the esophagus and teeth.

Self-Care at Home

Lifestyle modifications can relieve reflux symptoms. The following steps, if followed, may reduce reflux significantly:

- Refraining from eating three hours prior to bedtime. This allows the stomach to empty. Without food stimulation, the stomach’s hydrochloric acid production decreases.

- Avoiding lying down right after having eaten at any time of day. Elevation of the head six inches off of the bed. Gravity helps prevent reflux.

- Avoiding the ingestion of large meals. Eating a lot of food at one time increases the amount of acid needed to digest it. The alternative is to eat smaller, more frequent meals throughout the day.

- Avoiding fatty or greasy foods, chocolate, caffeine, mints or mint-flavored foods, spicy foods, citrus, and tomato-based foods. These foods decrease the competence of the lower esophageal sphincter.

- Avoiding alcohol ingestion. Alcohol increases the likelihood of acid reflux.

- Smoking cessation. Smoking weakens the lower esophageal sphincter and increases reflux.

- Losing excess weight. Overweight and obese people are much more likely to have bothersome reflux than people of healthy weight.

- Standing upright or sitting up straight and maintaining good posture. This helps food and acid pass through the stomach instead of backing up into the esophagus.

- Discussing with health care provider the intake of certain medications such as over-the-counter pain relievers, including aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), or medicines for osteoporosis. These can aggravate reflux in some people.

Some of these changes may be difficult for people to make.

Medical Therapy

Nonprescription (over-the-counter) medications

Antacids

These are effective when taken one hour after meals and at bedtime because they neutralize acid already present. Some familiar brand names of antacids are Gaviscon, Maalox, Mylanta, and Tums.

Some are combined with a foaming agent. Foam in the stomach apparently helps prevent acid from backing up into the esophagus.

These agents are safe to use every day over a few weeks, but if taken over a longer period can cause side effects:

- Diarrhea

- Impaired metabolism of calcium in the body

- Buildup of magnesium in the body, which can damage the kidneys

Patients using these medications daily for more than three weeks should be encouraged to inform their health care provider about this.

Histamine-2 receptor blockers (H2-blockers)

These drugs prevent acid production. H2-blockers are effective only if taken at least one hour before meals because they don’t affect acid that is already present. Common H2-blockers are cimetidine (Tagamet), famotidine (Pepcid), ranitidine (Zantac), and nizatidine (Axid).

If self-care and treatment with nonprescription medication do not work, prescribed antacids would be the next step.

Prescription medications

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)

PPIs stop acid production more completely than H2-blockers. They block the production of an enzyme needed to produce stomach acid.

PPIs include omeprazole (Prilosec), esomeprazole (Nexium), lansoprazole (Prevacid), rabeprazole (Aciphex), and pantoprazole (Protonix).

Prilosec is now available over the counter.

Coating agents

Sucralfate (carafate) coats mucous membranes to provide an additional protective barrier against stomach acid.

Pro-motility agents

- Pro-motility agents include metoclopramide (Reglan, Clopra, Maxolon), bethanechol (Duvoid, Urabeth, Urecholine), and domperidone (Motilium).

- They help tighten the lower esophageal sphincter and promote faster emptying of the stomach.

- Health care providers often are reluctant to prescribe these medications because they have fairly significant side effects.

- Pro-motility agents also do not work as well as PPIs for most people.

- One of these agents, cisapride (Propulsid), has been removed from the U.S. market because of safety concerns related to lethal drug interactions.

Surgery

Changes in lifestyle and habits, nonprescription antacids, and prescription medications all must be tried before resorting to surgery. Because lifestyle changes and medications work well in most people, surgery is done on only a small number of people.

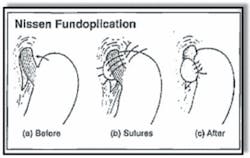

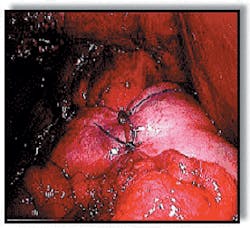

The operation used most often for GERD is called Nissen fundoplication (Figures 10-11).

- Fundoplication works by increasing pressure in the lower esophagus to keep acid from backing up.

- The surgeon wraps part of the stomach around the esophagus like a collar and tacks it down to provide more of a one-way valve effect.

- This procedure now can be done laparoscopically, without a large surgical incision. The surgeon makes a couple of very small cuts.

- This method leaves very little scarring and can produce a much faster recovery.

- Like all surgical procedures, fundoplication does not always work and can have complications.

Follow-Up

Reflux disease is treatable, but relapses are common. Patients should be encouraged to maintain an appropriate schedule of follow up appointments. The best therapy is to ensure compliance with prevention measures along with medical therapy.

If relapses occur, long-term therapy or surgery will be necessary to avoid complications.

Treatment of Dental Complications

There are several levels of therapy.

Recognition of Surface Changes

It is important to be aware of the various medical conditions that increase the risks of tooth wear. These include diseases that affect salivary glands or identification of the medications that decrease salivary function. Low salivary flow reduces its buffering and clearance effect, predisposing teeth to demineralization. In addition, it is necessary to be aware of the effects of associated psychiatric disorders such as bulimia and making appropriate referrals.

- Early recognition of surface changes is essential. It is the most important step in management of GERD-related risk. Initial signs include the first stages of erosion with chalkiness and loss of luster. More advanced erosion follows, with a corresponding increase in luster and transparency.

Remineralization therapy

Remineralization therapy is an important part of protecting the long-term health of the dentition. Remineralization treatments can be administered professionally and recommended as apart of a patient’s self-care routine. Not only will these treatments help patients with erosion due to acid reflux, but they will also help to control damage to the enamel from other demineralization factors, such as excessive ingestion of acidic foods and beverages (e.g., soda pop, sports drinks, tomato based products and citrus foods and drinks).

Professional Treatments

Dental professionals routinely follow a patient's progress through regularly scheduled oral prophylaxis appointments. This is an appropriate opportunity to administer a remineralization treatment. The primary remineralization treatment at present is the use of a topical flouride through varnish application , rinses, and one-minute topical gel/foam for use in a disposable tray after completion of the prophylaxis.

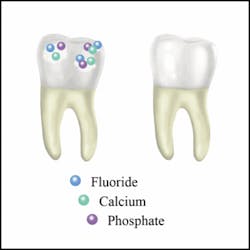

However, recent research findings indicate that application of pastes that include essential ions, such as calcium and phosphate, in addition to fluoride may be useful in the treatment of erosion. The combination of calcium, phosphate, and fluoride has been shown to be effective in inhibiting dissolution of enamel (demineralization) and filling of surface defects (Figure 12). Due to the fact that mixing calcium and phosphate results in solid crystals of calcium phosphate, it is important to keep these two agents in different compartments prior to their dental delivery. Usually the delivery system physically separates the active components to prevent the formation of calcium phosphate crystals.

Self-Care Dental Therapy

Homecare options for increasing fluoride are oral rinses and concentrated gels, including the use of 1.1 percent prescription-required gels and toothpastes. Fluoride-containing dentifrices have been introduced into the marketplace that can effectively deliver fluoride along with soluble sources of calcium and phosphate for effective delivery of ACP (amorphous calcium phosphate). Furthermore, brushing with products high in sodium bicarbonate will aid in neutralization of acids and their harmful effects while being very low in abrasion. The hign sodium bicarbonate products can be identified by looking to see if it is among the first ingredients listed in the “other ingredients” list. Although listed as a drug inactive, this does not diminish the functionality of sodium bicarbonate for this important role. A dentifrice that can help remineralize the teeth offers protection by continually abating the erosion process, and since patients routinely use dentifrices there is no issue of compliance for this therapy.

Restorative

Restorative options will depend on the degree of tooth surface loss. In early erosion, restorative options include use of dentin bonding agents to protect exposed dentin, resin restorations retained with adhesive agents in surfaces not susceptible to heavy loads, and veneer restorations. In advanced erosion, which involves a large amount of dentin exposure and loss of vertical dimension, orthodontic extrusion and full coverage restorations may be necessary.

Other Preventive Measures

- Avoidance of toothbrushing after acid exposure of the teeth, whether by an intrinsic or extrinsic source

- Using toothpaste, preferably a low-abrasive formula

- Including modifications to reduce the extrinsic sources of acid, including reduction of dietary acids and/or careful rinsing of the mouth after acid exposure

- Use of a protective occlusal guard if attrition due to bruxism is present

- Use of a neutralizing agent such as sugar-free antacids held in the mouth after acid exposure

- Salivary flow stimulation by use of nonacidic sugarless candies.

In Conclusion

One way dental professionals can be proactive in preserving and protecting the dental health of their patients is to be aware of any factors that may affect the dentition. The patient’s medical history can be reviewed to evaluate the potential for damage due to erosion from acid reflux. The listing of certain medications or the answering of specific questions are telltale signs that a patient may need continued monitoring and/or additional therapeutic recommendations. Furthermore, the presence of advanced erosion may require additional questioning of the patient with a possible physician referral.

References

1.Shi G, Bruley des Varannes S, Scarpignato C, et al: Reflux related symptoms in patients with normal oesophageal exposure to acid. Gut 37:457, 1995.

2.Wienbeck M, Barnert J: Epidemiology of reflux disease and reflux esophagitis. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 156:7, 1989.

3.Sonnenberg A, El-Serag HB: Clinical epidemiology and natural history of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Yale J Biol Med 72:81, 1999.

4.26. Dent J, Holloway RH, Toouli J, Dodds WJ: Mechanisms of lower oesophageal sphincter incompetence in patients with symptomatic gastrooesophageal reflux. Gut 29:1020, 1988.

5.Mittal RK, Holloway RH, Penagini R, et al: Transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. Gastroenterology 109:601, 1995.

6.Barham CP, Gotley DC, Mills A, Alderson D: Precipitating causes of acid reflux episodes in ambulant patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut 36:505, 1995.

7.The role of hiatus hernia in GERD. Yale J Biol Med 72:101, 1999.

8.Kahrilas PJ, Shi G, Manka M, Joehl RJ: Increased frequency of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation induced by gastric distention in reflux patients with hiatal hernia. Gastroenterology 118:688, 2000.

9.87. Carlsson R, Dent J, Bolling-Sternevald E, et al: The usefulness of a structured questionnaire in the assessment of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 33:1023, 1998.

10.Joelsson B, Johnsson F: Heartburn-the acid test. Gut 30:1523, 1989.

11.Jacob P, Kahrilas PJ, Vanagunas A: Peristaltic dysfunction associated with nonobstructive dysphagia in reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci 35:939, 1990.

12.97. Shaker R, Milbrath M, Ren J, et al: Esophagopharyngeal distribution of refluxed gastric acid in patients with reflux laryngitis. Gastroenterology 109:1575, 1995.

13.Jack CI, Calverley PM, Donnelly RJ, et al: Simultaneous tracheal and oesophageal pH measurements in asthmatic patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux. Thorax 50:201, 1995.

14.Yu ML, Ryu JH: Assessment of the patient with chronic cough. Mayo Clin Proc 72:957, 1997.

15.Katz PO, Dalton CB, Richter JE, et al: Esophageal testing of patients with noncardiac chest pain or dysphagia: Results of three years’ experience with 1161 patients. Ann Intern Med 106:593, 1987.

15.Katz PO, Dalton CB, Richter JE, et al: Esophageal testing of patients with noncardiac chest pain or dysphagia: Results of three years’ experience with 1161 patients. Ann Intern Med 106:593, 1987.

16.Lazarchik DA, Filler SJ. Effects of gastroesophageal reflux on the oral cavity. Am J Med. 1997; 103(5A):107S-113S.

17.Bowen WH, Tabak LA, eds. Cariology for the nineties. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1993.

18.Mandell ID. Caries prevention: current strategies, new directions. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996; 127:1477-1488.

19.Lussi A, Jaeggi T, Zero D. The role of diet in the aetiology of dental erosion. Caries Res. 2004; 38(suppl 1):34-44.

20.Touyz LZ. Fruit induced sensitivity at cervical margins. Jdent Assoc S Afr. 1983; 38:199-200.

21.Phelan J, Rees J. The erosive potential of some herbal teas. J Dent. 2003; 31:241-246.

22.Sullivan RE, Kramer WS. Iatrogenic erosion of teeth. ASDC J Dent Child. 1983; 50:192-196.

23.Milosevic A. Toothwear:aetiology and presentation. Dent Update. 1998; 25:6-11.

24.Smith JS, Ersen E, Coffman L, et al. Profilometry and scanning electron microscopy-a powerful combination. J Dent Res. 2004; 83(spec iss):2161.

25.Rytomaa I, Jarvinen V, Kanerva R, et al. Bulimia and tooth erosions. ACTA Odontol Scand. 1998; 56:36-40.

26.Pontefract HA. Erosive tooth wear in the elderly population. Gerodontology. 2002; 19:5-16.

27.Malfertheiner P, Hallerback B. Clinical manifestations and complications of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Int J Clin Pract. 2005 Mar; 59(3):346-355.

28.Schindlbeck NE, Klauser AG, Voderholzer WA, Muller-Lissner SA: Empiric therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Arch Intern Med 155:1808, 1995.

29.Schenk BE, Kuipers EJ, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, et al: Omeprazole as a diagnostic tool in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 92:1997, 1997.

30.Younes Z, Johnson DA: Diagnostic evaluation in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 28:809, 1999.

31.Patti MG, Gorodner MV, Galvani C, Tedesco P, Fisichella PM, Ostroff JW, Bagatelos KC, Way LW.Spectrum of esophageal motility disorders: implications for diagnosis and treatment.

32.Arch Surg. 2005 May; 140(5):442-8; discussion 448-9.

33.Wiener GJ, Morgan TM, Copper JB, et al: Ambulatory 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring: Reproducibility and variability of pH parameters. Dig Dis Sci 33:1127, 1988.

34.Meining A, Classen M: The role of diet and lifestyle measures in the pathogenesis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 95:2692, 2000.

35.Lowe RC, Wolfe MM. The pharmacological management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2004 Sep; 50(3):227-37.

36.McCallum RW: Clinical pharmacology forum: Motility agents and the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Med Sci 312:19, 1996.

37.Johnsson F, Holloway RH, Ireland AC, et al: Effect of fundoplication on transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxation and gas reflux. Br J Surg 84:686, 1997.

38.Imfeld T. Prevention of progression of dental erosion by professional and individual prophylactic measures. Eur J Oral Sci. 1996; 104(2 pt 2):215-220.

39.White DJ. The application of in vitro models to research on demineralization and reminerlization of the teeth. Adv Dent Res. 1995;9:175-193

40.Buchalla W, Attin T, Schulte-Monting J, et al. Fluoride uptake, retention and reminerlization efficacy of a highly concentrated fluoride solution on enamel lesions in situ. J Dent Res. 2002; 81:329-333.

41.Featherstone JD, Glena R, Shariati M, et al. Dependence of in vitro demineralization of apatite and reminerlization dental enamel on fluoride concentration. J Dent Res. 1990; 69(spec iss):620-625.

42.Whitford GM, Wasdin JL,Schfer TE, et al. Plaque fluoride concentrations are dependent on calcium plaque concentrations. Caries Res. 2002; 36:256-265.

43.Ghasemi A, Winston A, Charig A, et al. Intra-oral evaluation of a two-phase calcium-containing bicarbonate tooth-paste. J Dent Res. 2004;83(spec iss).

44.Charig A, Winston A, Flickinger M. Surface mineralization of etched enamel by calcium-containing bicarbonate tooth-paste. J Dent Res. 2004; 83(spec iss).

45.Putt MS, Milleman KR, Milleman KR, et al. Removal of tooth stain by bicarbonate, calcium and phosphate-containing dentrifice. J Dent Res. 2004:83.Abstract 4028.

45a. BT Amaechi, BT and Higham, SM. Dental erosion: possible approaches to prevention and control. Journal of Dentistry 33:243-252, 2005

46.Chu FC, Yip HK, Newsome PR, et al. Restorative management of the worn dentition: I. Aetiology and diagnosis. Dent Update. 2002; 29:162-168.

47.Yip HK, Smales RJ, Kaidonis JA. Management of tooth tissue loss from erosion. Quintessence Int. 2002; 33:516-520.

Registered Trademarks

- Advil (Wyeth Consumer Healthcare inc., Madison, NJ);

- Tedral (Park-Davis, Parsippany, NJ);

- Hydrophed (Watson Laboratories, Corona, CA);

- Marax (Pfizer, New York, NY);

- Quibron (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ);

- Maalox (Novartis Consumer Health, Summit, NJ);

- Motrin & Mylanta (McNeil, Ft. Washington, PA);

- Tums, Gaviscon, Zantac, Tagamet, and Maxolon (GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC);

- Pepcid and Motilium (Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ);

- Axid (Reliant Pharmaceuticals, Liberty Corner, NJ);

- Prolosec (Procter & Gamble, Cincinatti, OH);

- Nexium (Astra Zeneca, Wilmington, DE);

- Aciphex (Eisai, Inc., Teaneck, NJ);

- Protonix (Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories, Philadelphia, PA);

- Carafate (Axcan, Birmingham, AL);

- Reglan (Schwarz Pharma, Inc., Milwaukee,WI);

- Clopra (Quantum Pharmics, Amityville, NY);

- Duvoid (Roberts Pharmaceutical Corp., Eatontown, NJ);

- Urecholine & Urabeth (Odyssey Pharmaceuticals, East Hanover, NJ);

Note: Some drugs may be marketed and/or distributed in the U.S. under a different company name.

Author Profiles

Vincent W. Yang, M.D., Ph.D.

Vincent Yang, M.D., Ph.D., is the R. Bruce Logue professor of medicine and director, Division of Digestive Diseases, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA. He also holds an appointment as professor of hematology and oncology at Emory’s Winship Cancer Institute and is Director of Emory Epithelial Pathobiology Research Development Center. Dr. Yang is a renowned academic gastroenterologist with expertise in the field of colon cancer biology. He is also a clinical researcher in the area of chemoprevention of colon cancer and other GI cancers. As a clinician, he is an expert in the field of digestive diseases, including inflammatory bowel diseases, GI cancers, irritable bowel syndrome, peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and various techniques related to gastrointestinal endoscopies, including capsule endoscopy.

Dr. Yang holds memberships in numerous national and international organizations and committees, is an organizer of many national and international conferences, and serves on the editorial boards of the Archives of International Bioscience and Gastroenterology, as well as consultanting for the National Institutes of Health. He is the president elect of the Gastroenterology Research Group and vice chair of the GI Oncology Section of the American Gastroenterological Association. Dr. Yang is a recipient of numerous honors and awards, including the Georgia Cancer Coalition Distinguished Cancer Clinician Scientist, and is a member of the Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society, the American Society for Clinical Investigation, and the Association of American Physicians.

Dr. Yang received a B.Sc. from the Department of Agricultural Chemistry, National Taiwan University, Taipei, in 1976, a Ph.D. from the Department of Biochemical Sciences, Princeton University, in 1980, and in 1984 an M.D. from the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey-Rutgers Medical School (now Robert Wood Johnson Medical School). He completed his internship and a residency in the Department of Medicine at Johns Hopkins Hospital. He was a clinical fellow in the Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, from 1986 to 1989 and a research fellow in the Department of Biological Chemistry from 1987 to 1989 at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Dr. Yang was first assistant professor, then associate professor, in the of Division of Gastroenterology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine between 1989 and 2001.

Mohammad Wehbi, M.D.

Dr. Wehbi is an assistant professor in the Department of Gastroenterology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA. He is certified by the American Board of Internal Medicine. Dr. Wehbi has held various organizational positions, most recently as chairman of the Academic Committee, Atlanta Medical Center, Department of Internal Medicine, and as a medical advisor for the Young Adult Ministry of the Catholic Archdiocese of Atlanta. In addition, he worked as a government liaison for medical affairs in Beirut, Lebanon.

Dr. Wehbi holds memberships in various medical societies including the American Gastroenterological Association, the American College of Physicians, the American Medical Association, and the Lebanese Order of Physicians.

Dr. Wehbi has received many awards in recognition of his clinical expertise as well as his presentation of research. His articles have been published in various journals including Clinical Cancer Research, Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, and the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.

If you have any questions or comments for the authors of this CE course, please e-mail [email protected]. Please reference course title and author.

Disclaimer

The authors of this course have no commercial ties with the sponsors or the providers of the unrestricted educational grant for this course.

Reader Feedback

We encourage your comments on this or any ADTS course. For your convenience, an online feedback form is available at www.ineedce.com.