About 80% of my clinical full-time endodontic practice is retreatment of failed root canals and completion of teeth that have been accessed and remain uncompleted. It is my bias — in the vast majority of these cases — that a different preoperative case assessment would, could, or should have led to an initial referral or perhaps a different treatment algorithm on the part of the initial clinician.

A recent article in the Journal of Endodontics, “Analysis of the Cause of Failure in Nonsurgical Endodontic Treatment by Microscopic Inspection During Endodontic Microsurgery,” by Song, et al. (Vol. 37, Issue 11, Pages 1516-1519, November 2011) speaks to this point. The authors reported that … the most common possible cause of failure was perceived leakage around the canal filling material (30.4%), followed by a missing canal (19.7%), underfilling (14.2%), anatomical complexity (8.7%), overfilling (3.0%), iatrogenic problems (2.8%), apical calculus (1.8%), and cracks (1.2%). The frequency of possible failure causes differed according to the tooth position (P < .001). They went on to conclude: An appreciation of the root canal anatomy by using an operating microscope in nonsurgical endodontic treatment can make the prognosis more predictable and favorable.

While some degree of clinical misadventure is inevitable, can we not reduce such reasons for failure to a large degree through optimal preoperative planning? How is it that approximately 20% of the failures described above result from missed canals in an age of cone beam technology, digital radiographs, and a very clear understanding of canal morphology and anatomy?

What are optimal strategies to avoid these clinical shortcomings? While an exhaustive answer is well beyond the scope of this short article, several key points must be considered:

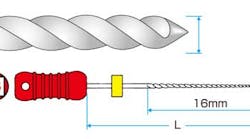

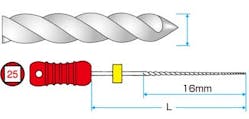

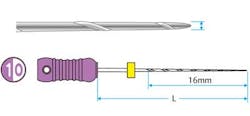

1. Not all teeth should be treated the same. Anatomy dictates technique. Having only one clinical instrumentation or obturation technique is not adequate when the tooth dictates a different method than the one generally employed. For example, if the clinician only has standard K files (Mani K files) and the canal is calcified, having the option of employing a hand K file designed for such calcification (Mani D finders) allows more efficient negotiation of calcification. Having only one hand file option or using the wrong hand file can lead to iatrogenic outcomes (blocked, ledged canals among other issues). See Figs. 1-2. Similarly, using a crown-down approach to instrumentation may risk iatrogenic outcomes when a step-back approach is more appropriate.

2. Experience is key. If the clinician is not the optimal person to tackle a given tooth, the patient should be referred. Starting a tooth in the vain hope of being able to complete the case is rarely, if ever, in the best interest of the patient. Instructions from manufacturers, lectures by key opinion leaders, and advice from colleagues are all important, among other sources of knowledge. But it is one thing to talk about treating patients and another to actually treat them. For the general dentist, asking oneself honestly if the patient is one he or she wishes to treat and the tooth is within his or her comfort zone can go a long way to a true assessment of which patients to treat in-house and which to refer. Know the tooth and — more importantly — know your patient.

3. Prior to initiating treatment, perform several assessments. Elaborating on the advice to “know the tooth” much could be written, but at a minimum, a complete preoperative examination and assessment with regard to endodontic diagnosis, clinical anatomy, restorability, periodontal status, optimal method of postoperative coronal seal, and detailed informed consent are essential before initiating treatment and will go far toward anticipating the causes of failure listed in the study above. In addition and aside from the clinical issues above, the clinician should ask if the tooth can and should be saved in the context of the patient’s medical and dental history, and most importantly the patient’s desires.

While all of these assessments are critical, it is the last component — assessing the patient’s wishes and needs in a frank and honest manner — that ultimately sets the stage for excellent clinical treatment. If the clinician has correctly assessed the clinical situation (as well as his or her own capabilities, equipment — surgical microscope or at a minimum loupes — and experience) and explained the planned treatment, risks, and alternatives and answered the patient’s questions ... and the patient wishes to proceed ... this is an environment in which excellent treatment can take place. This stands in contrast to a patient who is in the middle of caries removal where the pulp is exposed and a root canal is initiated on a patient with no prior conversation of such a possible outcome. This latter scenario is not a recipe for long-term clinical success or relationship building with the patient.

I welcome your feedback.

Author bio

Dr. Richard E. Mounce is in full-time endodontic practice in Rapid City, S.D. He has lectured and written globally in the specialty. Dr. Mounce owns MounceEndo, LLC, marketing the rotary nickel titanium MounceFile in Controlled Memory© and Standard NiTi. MounceEndo, LLC is an authorized dealer of Mani, Inc. stainless steel hand files and burs and W&H reciprocating handpiece attachments. You may contact Dr. Mounce by email at [email protected] or visit www.MounceEndo.com. Follow him on Twitter @MounceEndo.