So off I went to the “specialist” who can, according to my dentist, “deal with kids like your son,” they told my mom. Guess what? I refused again … well, until the dentist abruptly slapped his hand over my mouth and brought his face within millimeters of mine. His eyes pierced my soul with his scary stare as he spoke in a threatening tone, with such intensity as to jolt me out of my skin. Any sense of control I had fled as my body chemically bonded to the chair. My mouth opened so big that Cookie Monster’s mouth seemed miniscule in comparison. All I had done was refused to open. Did it work? Did I do as I was asked without hesitation? Absolutely! However, the essential question is: Was the method appropriate? Back then maybe so, but that was 37 years ago.

Every child presents new and different challenges; e.g., the 4-year-old who won’t let go of Mom’s leg, or the 9-year-old boy with three earrings who can curse up a storm and acts all macho but screams in terror at the sight of the exam mirror. Not to mention the 3-year-old with 18 carious lesions and a severe heart condition. The scenarios are endless.

Why do some young patients walk in happy as a puppy and endure siting still for 20 minutes with their faces feeling like they fell off, while others scream, kick, hit, and hide under the bench?

The dental office experience is no different than the playground. To deal positively with that stimulus takes capacity. It is the provider’s responsibility to deal with the outward expression of that stimulus. Behavior management is a way to deal with that unique expression. Since each child’s capacity is different, different methods are needed to control the dental situations. The patient’s perception has huge effects on dental experience as well. By controlling capacity and perception, we as providers can redirect the behavior in order to accomplish the task needed. There are ways in which the experience of a dental visit can be controlled to be helpful for everyone.

Parents are a good start for a positive dental visit. Parents need to know you are qualified and that you have the best intentions. Children can sense their parent’s fear and anxiety. Parents can unintentionally transfer fear to the child before even walking in the office.

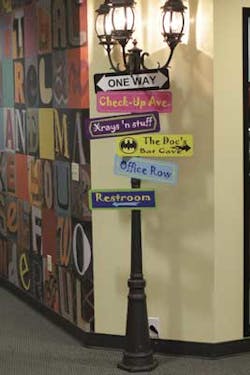

To create positive stimuli, there needs to be a child friendly environment. Remember, perception is important. Kids need to know it’s OK for them to be at the office. An office full of items that cannot be touched or enjoyed may not be the best invitation for a child. How can a child relax if there is a feeling that the office is a no-child zone? Pediatric offices are set up just for them. It can be like a fun park. I am not suggesting you redo your office, but a friendly, inviting office is a good start in behavior management.

Friendly staff is also key. I visited an office where a large sign on the desk read, “Children’s butts belong in the chairs. Thank you.” The lady behind the desk reminded me of the grouchy, old witch I once saw in a scary movie. This scenario is probably not a good start. Removing the sign and placing a smiley person behind the desk changes the patient’s whole perception and experience.

It is not easy to get a young patient through a dental appointment. It takes time and sometimes lots of failed attempts. What you see or hear other providers doing may not work for you. Learn the techniques and AAPD guidelines. Figure out what works for you and use it. Learn to perceive each patient’s capacity and perception and adjust your delivery to match. Do all this while providing a fun, safe, and controlled environment. This ideal environment is challenging to create, I know. Personally, I find parents the biggest challenge to manage. I cannot seem to find a textbook, clinical guideline, or advice on that one. But that is another article.