Balancing Your Musculoskeletal Health

Whoever coined the phrase “my job is a pain in the neck” could have been a female dentist. In few careers can this phrase be interpreted more literally than among women in dentistry.

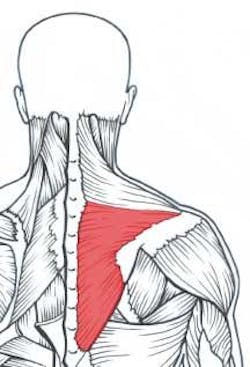

The primary shoulder-stabilizing muscles, the middle and lower trapezius muscles, fatigue quickly with forward head and abducted arm postures.

Compared to the average female worker, female dental professionals experience two to four times more musculoskeletal pain.1 Studies reveal that female dentists, in particular, tend to be more prone to neck and shoulder pain than their male counterparts.2-4 Female dentists face a unique set of musculoskeletal challenges when delivering dental care that can result in muscle imbalances, ischemia, nerve compression, and joint or disc degeneration.

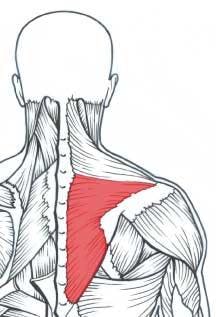

When the shoulder-stabilizing muscles fatigue, other muscles must compensate, thus becoming overworked, ischemic, and painful.

Dentists tend to hold one posture for a longer period of time than hygienists, meaning that dentists must have excellent endurance of the stabilizing muscles of the neck and shoulder in order to have optimal hand and arm function and to avoid musculoskeletal dysfunction. On average, women’s muscles can exert only two-thirds the force of men’s.5 What this means for female dentists is that when the head moves forward, out of neutral position, there is generally less muscle to stabilize the neck.

Maintaining optimal neck and shoulder musculoskeletal health for female dentists means understanding the unique muscle imbalances to which they are prone and how various working postures, positions, adjustment of ergonomic equipment, and exercise can positively or negatively affect the involved muscles.

Muscle imbalances

The delivery of dentistry requires substantial endurance of the shoulder girdle stabilizing muscles, especially the middle and lower trapezius muscles (Figure 1a). These shoulder-stabilizing muscles tend to fatigue quickly with forward head, rounded upper back, and elevated arm postures commonly seen among female dentists. When these muscles fatigue, other muscles (upper trapezius, levator scapula, and upper rhomboids) must compensate and thus become overworked, tight, and ischemic (Figure 1b).6

This muscle imbalance may result in a “tension neck syndrome,” and is one of the most frequently diagnosed musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) among female dentists.7 Symptoms include pain, tenderness, and stiffness in the neck and shoulder musculature, often with muscle spasms. A typical symptom among female dentists is pain that may radiate between the shoulder blades or up into the occiput. Headache is also a common symptom. Two contributing factors to tension neck syndrome in dentistry are forward head and elevated arm postures.

Forward head posture

Optimal posture of the head is ears-over-shoulders when viewed from the side. Unfortunately, dentists do not achieve this neutral position while working in the operatory unless they are using a microscope. Even with telescopes, the best head posture that dentists can attain is about 25 degrees of forward head tilt;8 however, when compared with postures of their colleagues who do not wear scopes (40 to 60 degrees forward head tilt), the ergonomic advantage of scopes becomes clear.

Women dentists’ first line of defense against neck and shoulder pain is to learn how to attain optimal head posture and shift the muscle workload throughout the workday. Next, they should address muscle imbalances to which they are prone by stretching specific tight muscles, strengthening shoulder-stabilizing muscles, and avoiding exercises that stress the already-overworked muscles.

Magnification

Properly adjusted scopes can reduce muscle strain in the neck and upper back by promoting proper neck and shoulder posture.9 Two of the most critical factors to consider when purchasing scopes are working distance and declination angle.

Working distance is the distance from the operator’s eye to the working area. Measure the working distance in your own operatory, if possible, with arms relaxed at your sides and forearms approximately parallel to the floor.

Properly adjusted scopes, combined with seating that opens the hip angle, allows lower and closer positioning of the patient, and helps reduce neck strain.

Bambach saddle stool courtesy of Hager Worldwide.

From an ergonomic and musculoskeletal standpoint, the declination angle of the scopes is your most important consideration. The declination angle is the steepness of the downward viewing angle the scopes allow. A good declination angle will allow you to work with a more upright, neutral neck posture, about 25 to 30 degrees of neck flexion (head tilt) (Figure 2). Even then, working in postures with greater than 20 degrees of neck flexion has been associated with increased neck pain.10 This means dentists must not only address the ergonomic magnification component but the muscular as well, by strengthening the shoulder girdle stabilizing muscles.

Correct height

Possibly one of the biggest contributing factors to neck and shoulder pain among female dentists is positioning the patient too high. This causes elevation of the shoulders and abduction of the arms, leading to prolonged, static muscular tension in the neck and shoulders. Magnification enables operators to maintain a greater working distance and position patients lower, with shoulders relaxed and forearms approximately parallel to the floor.

Open the hip angle

To maintain optimal head posture, you must be able to get close to the patient. A common problem among shorter female dentists is the inability to get their legs under the patient chair without lifting the arms away from the sides. A tilting seat may enable closer positioning to the patient by opening the hip angle. Now you can position the patient slightly lower to decrease “chicken-winging.” Additionally, tilting the seat pan 10 to 15 degrees forward has been shown to help maintain the low back curve and reduce low back disc pressures,11,12 which can, in turn, help reduce low back pain.

An example of a strengthening exercise for the middle and lower trapezius muscles using an elastic exercise band.

A saddle-style stool will allow the closest positioning to the patient by placing the operator in a position partway between standing and sitting (Figure 2). This opens up the hip angle to about 140 degrees, helps promote the spine’s natural curves, and shifts the workload to different muscles than those used with traditional seating. For this reason, it may be desirable to have one of each type of stool in the operatories to alternate working postures and prevent overworking the same muscles. Ask to test operator stools prior to purchasing them.

Some female dentists have modesty issues and prefer a comfortable distance between their chest and the patient’s head. This will cause them either to lean forward, which increases forward head posture, or to sustain a forward reach with the arms, causing neck strain. Opening the hip angle and using magnification will enable lower positioning of the patient and help address this common problem.

Armrests

Among dentists who already experience neck pain, the simple weight of the arms hanging unsupported at the sides may often perpetuate that pain.13 Armrests can reduce such strain by providing an operating fulcrum at the elbow, which also improves instrument stability. Dentists with neck pain who have short arms should consider support under the elbows at home as well as in the operatory, when driving, sitting on a couch, or at the computer.

Women's issues

The weight of large breasts can cause bra straps to dig into the upper trapezius muscle, exacerbating the muscle imbalance, and may cause headaches. A sports-type bra with wide straps that connect in the middle of the upper back can translate this weight to a wide support band under the breasts and may help reduce pain when worn during work.

Out of the operatory, a large shoulder bag may also compress the upper trapezius in a similar manner. A backpack-style purse distributes the weight more evenly and should be considered by female dentists.

Additionally, the upper trapezius muscle is susceptible to emotion. During times of emotional stress, it may be held elevated and tense. Learn to sense this tension and release it throughout the day. One method is with frequent shoulder rolls, each time returning the shoulders to a relaxed, neutral position.

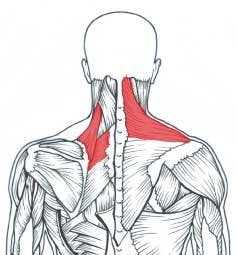

Strengthening

All exercise is not necessarily good exercise for female dentists. Due to their susceptibility to the muscle imbalance described earlier, most women dentists should focus on specific strengthening of the shoulder-stabilizing muscles and steer away from exercises that strengthen the upper traps, levator, and upper rhomboids, muscles that are already prone to tightness, ischemia and pain.

The middle and lower trapezius muscles may be strengthened by utilizing an elastic exercise band and pulling diagonally downward, squeezing the shoulder blades downward and together (Figure 3). Always use a very light resistance when strengthening postural stabilizing muscles and seek professional guidance from a health-care professional to ensure good technique.

Using an exercise band in the reverse manner of Figure 3 (i.e., pulling diagonally upward toward the body) may over-strengthen the upper trapezius, worsening muscle imbalance. Instead, focus on aerobic health of the upper trapezius and choose activities that swing the arms, like walking, swimming, cross country skiing, or the NordicTrack exerciser.

Additional target areas for dentists to strengthen include the shoulder external rotators, transverse and oblique abdominals, multifidus, and deep postural neck muscles. Strengthening exercises should only be performed when there is no musculoskeletal pain and full range of motion is present.

Self-therapy

Tightness, ischemia, and trigger points in the upper back and neck muscles should also be addressed daily with specific chairside stretching and trigger point self-therapy.14

The possible etiologies of neck and shoulder pain among female dentists are numerous, including neurological, spinal disc, joint, ligamentous, and other pain mechanisms. Most frequently, however, neck and shoulder problems originate from postural problems that lead to muscle imbalances. If these imbalances are not addressed, they can eventually compress nerves and discs and cause joint dysfunction.

Education of this type in dental schools may help dentists develop healthy postural habits and maintain balanced musculoskeletal health before they sustain a permanent musculoskeletal injury. Addressing muscular pain early on can make the difference between a satisfying, lengthy career or painful early retirement.

References

1 Akesson I, Schutz A, Horstmann V, et al. Musculoskeletal symptoms among dental personnel; lack of association with mercury and selenium status, overweight, and smoking. Swedish Dental Journal 2000; 24:23-28.

2 Rundcrantz B, Johnsson B, Moritz U. Cervical pain and discomfort among dentists. Epidemiological, clinical, and therapeutic aspects. Swedish Dental Journal 1990; 14:71-80.

3 Marshall E, Duncombe L, et al. Musculoskeletal symptoms in New South Wales Dentists. Australian Dental Journal 1997; 42:240-246.

4 Chowanadisai S, Kukiattrakoon B, et al. Occupational health problems of dentists in Southern Thailand. International Dental Journal 2000; 50:36-40.

5 Kroemer K, Grandjean E. Fitting the task to the human, 5th ed. Taylor & Francis; Philadelphia, Pa., 1997.

6 Novak C, Mackinnon S. Repetitive use and static postures: a source of compression and pain. Journal of Hand Therapy April 1997; 151-159.

7 Akesson I, Johnsson B, Rylander L, et al. Musculoskeletal disorders among female dental personnel - clinical examination and a five-year follow-up study of symptoms. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 1999; 72:395-403.

8 Chang B. Ergonomic benefits of surgical telescope systems: Selection Guidelines. CDA Journal 2002; 30:2:161-169.

9 Branson B, Bray K, Gadbury-Amyot C, Keselyak N, Mitchell T, Williams K. Effect of magnification lenses on student operator posture. Journal of Dental Education March 2004; 384-9.

10 Ariens G, Bongers P, Douwes M, et al. Are neck flexion, neck rotation, and sitting at work risk factors for neck pain? Results of a prospective cohort study. Occupational & Environmental Medicine 2001; 58:200-207.

11 Hedman T, Fernie G. Mechanical response of the lumbar spine to seated postural loads. Spine 1997; 22:734-743.

12 Harrison D, Harrison S, Croft A, et al. Sitting biomechanics part 1: review of the literature. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics 1999; 22:9:594-609.

13 Sahrmann S. Lecture in Portland, Ore.: Diagnosis and treatment of movement impairment syndromes. Feb. 7-8, 2004.

14 Valachi B, Valachi K. Preventing musculoskeletal disorders in clinical dentistry. Journal of the American Dental Association Dec. 2003; 134;1604-12.

Bethany Valachi, MS, PT, CEAS

Ms. Valachi is a physical therapist, dental ergonomic consultant, and owner of Posturedontics. A member of the National Speaker’s Association, she presents dental seminars internationally and has developed exercise videos for dental professionals. Contact her at bethany@ posturedontics.com.