Bucco-lingual 'dimple' technique for removing full-crown and cast-metal restorations

By Gerald L. Herman, DMDMany longitudinal studies have been made on the longevity of full-crown and cast-metal restorations. Dentists and dental team members marvel at the crown or bridge that has been in place and functioning for 30 or 40 years in a mature or elderly patient. Dental insurance company statistics and clinical records seem to indicate, however, that the average life span of a crown is closer to seven or eight years. How do you respond to the patient who asks, “Doctor, how long will this crown/bridge last?” Whatever your answer, it is realistic to expect that a newly inserted crown or fixed bridge will require replacement at some point in the patient’s lifetime.The operative removal of existing porcelain-fused-to-metal or full-cast metal crown restorations from teeth that are to receive new restorations can be traumatic for the patient and stressful for the clinician. Often, the restorative material(s) must be cut completely through with high-speed rotary instrumentation and then pried off with a narrow-ended hand instrument. Sometimes, multiple “slices” are required to facilitate removal of the crown. If the crown is composed of a non- or semiprecious alloy, removal becomes even more difficult, as the material is harder to penetrate. The intraoral cutting and grinding of porcelain and metal is an arduous task for everyone involved. Many patients find the excessive noise, vibration, and pressure objectionable. Particulate matter generated by this procedure may be inadvertently swallowed or inhaled by the patient despite the most careful chairside assisting and high-speed evacuation. The operator and clinical assistant are exposed to debris also, even while wearing surgical masks. Protective eyewear for the patient and dental team is recommended to prevent eye injuries from projectile matter.Many dentists consider this among their most stressful procedures, especially when multiple units are involved. The practitioner must be vigilant while cutting, making sure to stop when the cementing medium becomes visible, so as not to mutilate underlying tooth structure. If a cast post and core or amalgam core is present, the cement layer can easily be missed as the operative bur passes from metal to metal. If a composite core is underneath the casting, it can be difficult to distinguish between cement layer and core. Magnification with loupes is helpful while performing this task.The limitations of current radiographic methods, combined with the impossibility of seeing through radiopaque restorative materials, add to the unpredictability of this operation. The patient should be informed that there is a degree of uncertainty about the outcome before proceeding. The dentist cannot really know what is lurking underneath the crown until it is removed, nor does he or she know the thickness of the restorative materials until the coping is penetrated. Just about every dentist has had the nightmarish experience of attempting to remove a crown from an endodontically treated tooth that has been restored with a post only to discover that the post and crown are unit cast. The exasperated operator must then either attempt to remove the entire casting with post, or prepare the metal as if it were tooth structure to an appropriately sized core to receive a new crown. As with most procedures performed in the dental operatory, the practitioner must display patience, remain calm, and encourage the patient to relax during this painstaking and sometimes extremely time-consuming procedure.Gaining access for positioning the handpiece and visualization of the buccal surfaces may be problematic on maxillary second — and sometimes first — molars. In these instances, the lingual surface is more readily available for access. The disadvantage to this approach, however, is that there is usually a thicker layer of metal on the lingual than on the buccal surface, where there is often more of the easily penetrated veneering material and a thinner layer of metal. Another issue the operator has to consider is where to begin cutting the groove. Common sense from a leverage standpoint might indicate a mid-buccal approach, but that requires that the cutting instrument be placed very close to the delicate furcation area on certain teeth, that is, periodontally involved molars.Some practitioners and laboratory technicians are still using a “removal button” on the lingual collar of their cast restorations to assist in removing temporarily cemented units. The button acts as a purchase for a reverse- or back-action type of instrument that can “tap” off the crown. In my experience, many patients cannot or will not tolerate these buttons even on temporarily cemented cases. When used, the button is generally retained until the restoration is permanently cemented, at which point it is ground off and polished prior to cementation, thus making removal of a permanently cemented crown with a reverse action instrument difficult if not impossible.On multiple splinted units or fixed partial dentures, the beak of the tapping instrument can be used to engage the available gingival embrasure areas of the restoration for purchase to facilitate removal. Aggressive tapping should be avoided, especially on periodontally compromised teeth, endodontically treated teeth, or teeth that are otherwise challenged, as fractures or avulsions may occur. Also to be considered is that most patients consider this reverse action tapping to be quite unpleasant, not unlike a jackhammer in the mouth.In my practice, I routinely use an interim cement on compromised cases over the long term instead of a permanent cement. There are not too many scenarios in dentistry that are more confounding than a permanently cemented long-span or full-arch reconstruction in which the cement seal has failed on one terminal molar abutment. It is not my intention in this article to discuss nonrigid connections and stress-breaking attachments, but suffice it to say these must be considered and utilized strategically in large or compromised cases to prevent this type of problem. Cases that are designated for long-term, interim cementation must be monitored closely and recemented at regular intervals to prevent leakage, thermal sensitivity, and recurrent caries.One of the objectives of clinical dentistry should be to keep each procedure as streamlined as possible to ensure patient comfort while achieving an optimal clinical result (flawless crown margins, outstanding esthetics, etc.). The “dimple” technique can be utilized in certain clinical situations to lessen or eliminate the noxious intraoral grinding of porcelain and metal in removing cemented crowns and cast-metal restorations. A dimple is created on the gingival one-third of the buccal and lingual surfaces of the crown with a small round bur or the end of a straight or tapered operative bur (Fig. 1). The dimples will act as receptacles for the beaks of a Baade pliers (Buffalo Dental, Syosset, NY). The Baade pliers are typically used to remove acrylic provisional restorations as the beaks readily engage the resilient acrylic material. However, Baade pliers will slip off the smooth hard surfaces of porcelain and/or metal unless dimples are created (Fig. 2). Baade pliers are available in both straight and contra-angled variations for adaptability to different intraoral applications.

Fig. 1 — Dimple preparation on buccal surface of mandibular second molar PFM crown and palatal surface of maxillary second premolar PFM crown.

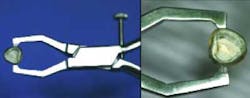

Fig. 2 — Dimples act as receptacles for beaks of Baade pliers.Once the dimples are made and the Baade pliers are in position (Fig. 3), the operator attempts to break the cement seal and remove the crown with a twisting motion of the hand and wrist. This technique works especially well on teeth with short clinical crowns and/or teeth that have been prepared with excessive taper. If the crown resists displacement using this technique, it is unwise to attempt to force the crown off with the Baade pliers, as the tooth may fracture. The dimple technique is also contraindicated on teeth with advanced loss of periodontal attachment, unfavorable crown-to-root ratio, or excessive mobility. In these cases, the crown should be sliced from the buccal gingival margin to the occlusal or incisal aspect and then pried off with a narrow-ended hand instrument.

Fig. 3 — Baade pliers in position to apply dimple technique, engaging buccal and lingual/palatal dimples.

Dimples can also be utilized on crowns that, even after being sliced and pried apart, still resist removal. In other words, a combination of techniques is sometimes necessary to remove the crown. But in cases where the dimple technique alone is successful, the delighted practitioner has removed the crown quickly and intact without any intraoral grinding, prying, or tapping (Fig. 4). There are situations in which it is desirable and even imperative to retrieve a crown intact and whole, such as when a porcelain fracture occurs on a permanently cemented crown that can possibly be repaired in the laboratory and recemented. In these instances, the dimple technique, if applied successfully, will prevent a costly and time-consuming remake.

Dimples can also be utilized on crowns that, even after being sliced and pried apart, still resist removal. In other words, a combination of techniques is sometimes necessary to remove the crown. But in cases where the dimple technique alone is successful, the delighted practitioner has removed the crown quickly and intact without any intraoral grinding, prying, or tapping (Fig. 4). There are situations in which it is desirable and even imperative to retrieve a crown intact and whole, such as when a porcelain fracture occurs on a permanently cemented crown that can possibly be repaired in the laboratory and recemented. In these instances, the dimple technique, if applied successfully, will prevent a costly and time-consuming remake.

Fig. 4 — Crown has been displaced from prepared tooth utilizing dimple technique. Note intact coping and cement layer.

An indispensible instrument for removing temporarily cemented crowns, or very retentive crowns during try-in appointments, is the GC pliers (GC America, Alsip, IL). The GC pliers are similar to the Baade pliers, except that it has replaceable rubber tips at the beak ends which grab the restoration and will not scratch newly finished porcelain or metal surfaces (Fig. 5). To facilitate removal of the crown, the operator may also use emery powder, a fine sand-like material that is supplied by the manufacturer and applied to the rubber tips to provide additional friction. The emery powder will not scratch glazed porcelain or polished metal surfaces either.

An indispensible instrument for removing temporarily cemented crowns, or very retentive crowns during try-in appointments, is the GC pliers (GC America, Alsip, IL). The GC pliers are similar to the Baade pliers, except that it has replaceable rubber tips at the beak ends which grab the restoration and will not scratch newly finished porcelain or metal surfaces (Fig. 5). To facilitate removal of the crown, the operator may also use emery powder, a fine sand-like material that is supplied by the manufacturer and applied to the rubber tips to provide additional friction. The emery powder will not scratch glazed porcelain or polished metal surfaces either.

Fig. 5 — GC pliers have replaceable rubber grips at beak end. Emery powder may be used for additional friction.Removal of permanently cemented cast metal onlays and partial coverage restorations presents another operative challenge. Many onlay preparations contain accessory retentive grooves and boxes, making the restoration extremely resistant to displacement. The operator may decide to utilize the dimple technique in a direct bucco-lingual approach as well as a mesio-buccal/disto-lingual approach and a disto-buccal/mesio-lingual approach in an attempt to dislodge and displace the restoration. In this variation of the technique, three dimples are created on the buccal and three on the lingual surface of the restoration. The Baade pliers can then engage and torque the casting in a variety of directions. If this is unsuccessful, “gouging” the exposed buccal, lingual, and proximal margins of the restoration with high-speed rotary instrumentation and a narrow operative diamond to a depth of approximately 1 mm to 1.5 mm and then reapplying the dimple technique may yield a good result.Sometimes, a piece of tooth structure will fracture off when the onlay is removed. This is usually a portion of prepared cusp or a section of enamel. In either case, this is not a major concern because a tooth with a failing partial coverage restoration will usually require re-treatment with full coverage. However, the removal of permanently cemented cast restorations, whether they are onlays or crowns, may be accompanied by more serious fractures, some of which may even render the tooth nonrestorable and necessitate extraction. Other moderately sized fractures may require osseous surgery and/or endodontic therapy and post and core buildup to make reconstruction of the tooth possible.The removal or retrieval of existing permanently cemented crowns and cast-metal restorations is not an exact science. It is unpredictable and not always without undesirable consequences. Patients should be fully informed about the uncertainty that exists before removal is attempted, the possibility of fracture, and best- and worst-case scenarios for reconstruction of the tooth or teeth, quadrant, or arch. It behooves the practitioner to have at his or her disposal a variety of techniques and instruments to perform this procedure. A technique has been presented in this paper, which, if applied judiciously, will greatly facilitate removal of permanently cemented full-crown and cast-metal restorations.Author bioDr. Gerald L. “Gerry” Herman, a board-eligible prosthodontist, is a specialist in oral rehabilitation and occlusion utilizing crowns, bridges, dentures, and implants for patients who are missing teeth or have advanced dental problems and esthetic concerns. He is the prosthodontic specialist at Park 56 Dental Group in New York City. Dr. Herman is considered one of New York City's finest cosmetic dentists with expertise in all of the latest techniques in smile enhancement, porcelain bonding, and teeth whitening. He also has attained advanced certification in Invisalign Orthodontics. Dr. Herman earned his DMD degree from the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine in 1982, and spent two years in private general practice in Philadelphia. In 1986, he received his certificate in prosthodontics from New York University College of Dentistry. Dr. Herman has held faculty appointments at the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine, New York University College of Dentistry, Mt. Sinai Hospital, and Peninsula Hospital. He has published articles in various dental journals, and he has lectured at scientific meetings and at hospitals. In addition to numerous television appearances to discuss topics in dentistry, he has contributed to several books in the areas of prevention of dental disease and cosmetic dentistry. Dr. Herman is a member of the American College of Prosthodontists, the American Dental Association, the Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry, and the First District Dental Society.