Body Image – ... too little of a good thing?

The media is swamped with ultra-thin female actors and models. The women who appear weekly as our "friends" may, in fact, be our truer enemies. Trainer-honed bodies appear regularly in all forms of media: print, television, and movies. Gone are the "Rubenesque," healthy-looking women — women who our grandmothers said had "meat on their bones." In their place are waifs, women who, if a gust of wind appears, may be blown over. As a result of these alleged icons on the screen and in magazines, young women have stylized their vision of health and happiness after sometimes unattainable goals. Some girls' bodies may not support the "thin is in" look, having deadly results.

These are not new issues. Eating disorders have been around a very long time. Evidence of anorexia nervosa and bulimia is present in Egyptian hieroglyphics and Persian manuscripts. Bulimia-like conditions were indicated on scrolls from early Chinese dynasties. Ancient Romans also used the bulimia forms of binging and purging via the use of a vomitorium, a special lavatory for the sole purpose of purging to allow themselves to return to the feast and eat more. In 1689 in London, Richard Morton made the first formal description of eating disorders. He described the first patient as a "skeleton clad in skin."1 Other documentation of anorexia in modern medical literature is from Lasegue in 1873 in France and Gull in 1874 in England. Initially, anorexia nervosa was thought to be a form of tuberculosis, hormonal imbalance, or endocrine deficiency. In the 1930s, researchers identified the cause to be self-starvation, with its associated psychological and emotional issues.

Eating disorders are "characterized by a persistent pattern of aberrant eating or dieting behavior. These patterns of eating are associated with significant emotional, physical, and relational distress."2 Approximately 7 million women are affected by these disorders. No socioeconomic group or ethnic group is untouched by this epidemic: 0.5 to 3.7 percent of late adolescent or adult women suffer from anorexia nervosa, and 1.0 to 2.2 percent of late adolescent and adult women have bulimia. It is estimated that between 2 and 5 percent of Americans exhibit binge-eating disorder. At any given time, 10 percent or more of college-age women report symptoms of eating disorders.

Although eating disorders appear to be a "female" issue, 10 percent, or approximately 1 million, of all individuals with these disorders are men.3 Men comprise 35 percent of individuals with binge-eating disorders. Studies have shown that for every four women with anorexia, there is one man; and for every eight to 11 women with bulimia, there is one man.4

There are many factors that control eating. Food choices are dependent on habits and patterns developed during childhood. They reflect family lifestyles as well as ethnic, cultural, social, religious, geographic, economic, and psychological components. Various forms of media have become an omnipresent influence of these controlling factors. For example, young women's fashions portrayed in music videos have a profound influence.

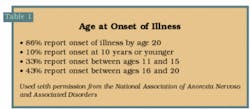

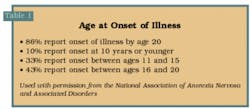

Eating disorders have their start usually in early adolescence, but some studies show they can begin during childhood or into adulthood (Table 1). The etiology of these disorders is unknown, but many factors contribute to their development (Table 2). Take the formula of a young woman just entering adolescence, who has low self-esteem plus a high, sometimes unrealistic, perfectionist tendency, throw in a possible competitive sport, and you have the recipe for an eating disorder. A family that is overly concerned with eating and weight is also considered a cause. Uncontrollable factors, such as low birth weight, maternal alcohol use or smoking during pregnancy, and severe early trauma have also been indicated as possible causes.

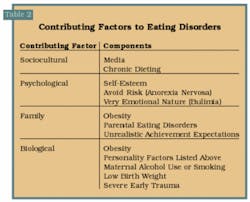

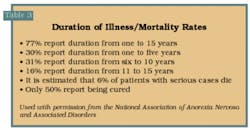

According to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders (ANON), duration of the illness varies from one to 15 years. The majority of individuals experience signs and symptoms by the age of 20. Once detected, treatment usually lasts at least two years. There is an estimated 6 percent mortality rate, and only 50 percent of patients are cured (Table 3).

Risk factors for men appear to be slightly different. Men begin eating disorders at a later age than women. Many were overweight as children and have been dieting. They are involved in sports or jobs that require sleek, lean bodies, such as runners, jockeys, or models. Treatment is the same for both sexes, although men are more reluctant to admit to having eating disorders.

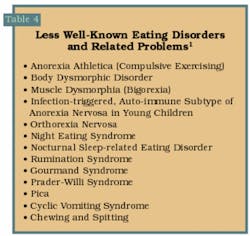

Eating disorders can be classified into three categories: anorexia nervosa, bulimia, and binge-eating disorder. Eating disorders not otherwise specified or those that do not fit into the complete diagnostic criteria of these three, as well as less well-known eating disorders, are listed in Table 4. For this article, only the first three categories will be discussed.

Individuals with anorexia nervosa are unwilling to maintain a body weight that is normal or acceptable for their age and height. There is no exact borderline dividing normal from too low, but most clinicians use 85 percent of normal weight as a reasonable guide. Individuals with anorexia nervosa usually display a pronounced fear of weight gain and a dread of becoming fat, even though they are markedly underweight. Concerns about their weight and about how they believe they look have a powerful influence on the individual's self-image. They "see" themselves as fat. The seriousness of the weight loss and its health implications are usually minimized, if not denied, by these individuals. Women with the diagnosis of anorexia have missed at least three consecutive menstrual cycles. In addition, studies have shown that women with a history of anorexia nervosa exhibit an increase in osteoporosis and bone fracture.5

Two subtypes of anorexia nervosa exist. Individuals with the restricting type maintain their low body weight by restricting food intake and possibly by exercise. Individuals with the binge-eating/purging type will usually restrict their food intake as well, but they also regularly engage in binge-eating or purging behaviors, such as self-induced vomiting or misuse of laxatives, diuretics, syrup of ipecac, or enemas.

Individuals with bulimia regularly engage in discrete periods of overeating that are followed by attempts at compensatory behavior for overeating and avoidance of weight gain. Again, profound concerns about weight and physical condition exist in the individual's mind. Considerable variation in the nature of the overeating exists, but a typical episode involves consumption of an amount of food that would be considered excessive in normal circumstances. There is a definite lack of control over eating, followed by attempts to undo the consequences with self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives, enemas, diuretics, diet pills, severe self-imposed caloric restrictions, or excessive exercising. Bulimia can be either purging or nonpurging (i.e., use of excessive exercise or fasting to rid the excess weight).

Binge-eating disorder involves frequent eating episodes without the purging. Individuals are more often obese (approximately 50 percent) and usually use inappropriate compensatory weight control behaviors, such as fasting, to lose the weight. Rapid consumption of food may occur or eating a large amount of food when not really hungry. There is a distinct loss of control over eating; food is eaten until a feeling of being "over-full" occurs. Patients usually exhibit feelings of guilt or embarrassment, similar to patients with anorexia nervosa. Historically, these patients were considered "compulsive overeaters," emotional overeaters, or food addicts. Approximately one-fifth of people who seek professional treatment for obesity have a binge-eating disorder.

There are eating disorders that are not otherwise specified (EDNOS), including disordered eating that does not fit the full diagnostic criteria for either anorexia nervosa or bulimia, but may exhibit components of the problem (e.g., a woman who maintains her menstrual cycle but is anorexic, or a person who binge-eats less than two times a week).

These eating disorders have definite negative physical and psychological impacts. Individuals with anorexia nervosa may exhibit malnutrition, dehydration, esophageal tears, and serious heart, kidney, and liver damage. Bulimic individuals experience intestinal ulcers and ruptured stomachs from constant purging. Semi-starvation can affect most organ systems. The psychological aspects of these disorders include depression, shame and guilt, mood swings, low self-esteem, impaired family and social relations, and an unrealistic perfectionism.3 There is a negative impact on the quality of life. Self-image, relationships, and professional performance are negatively affected.

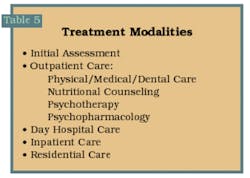

Treatment of eating disorders is multifaceted. Individuals are either outpatient or, in extreme cases, need to be assigned to residential care. The life-threatening aspect of these disorders puts individuals at a higher risk (Table 5). Initial patient assessment will evaluate the history and the severity of the eating disorder. Outpatient care usually is multilayered. Medical and dental evaluations reveal any systemic problems that have caused complications. Psychotherapy, nutritional counseling, or possible use of pharmacologic agents may be involved in treatment. Constant medical monitoring will be necessary. In addition to outpatient care, some individuals will enter a day hospital setting to allow for increased structure (e.g., specific eating situations and active treatment). This approach enables individuals to follow a normal daily routine, such as school or work. Inpatient care gives a structured and contained environment, with constant access to clinical support all day. Depending on the level of weight loss and malnutrition, residential care where the individual is taken into a facility for treatment may be necessary.

The dental team may be one of the first to notice any signs of eating disorders. Dental signs and symptoms of disordered eating are evident in routine intraoral and extraoral examinations. These signs include erosion of lingual enamel from purging, halitosis from constant purging, increased caries rate, enlargement of parotid gland, sore throat, traumatic ulcerations of the soft palate from forced vomiting, xerostomia, irritation to the lips and other soft tissues, and dentinal sensitivity. Some of these signs could be falsely assumed to be a result of poor personal dental hygiene care. Abrasions or calluses on the dorsal surfaces of the fingers and hands due to friction from self-induced vomiting will also be present. Additional physical assessment keys include: signs of malnutrition (thinning hair, always cold, fatigue, hypothermia, facial hair or lanugo, carotenemia), decreased ability to concentrate, depression, broken blood vessels in the eyes, and low body weight.

Eating disorders — for weight loss or for weight gain — are complex, multidimensional, serious disturbances in eating behavior that involve many facets, such as depression, anxiety, and appetite control to the level of self-starvation. They are maladaptive behaviors used to fit into a specific body image, either real or imagined. Dentistry can assist in the detection of signs and symptoms of these deadly illnesses. The signs can be subtle, but with knowledge and awareness we may be able to reveal a small problem before it becomes a larger health issue and elicit appropriate referrals to treat an individual's mental and physical well-being.

References

- www.anred.com (Anorexia Nervosa and Related Eating Disorders, Inc.)

- www.aedweb.org/disorders.html (Academy for Eating Disorders)

- www.anad.org/facts.html (National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders)

- http://eatingdisorders.about.com/library/mh/bled.htm (About, Inc.)

- Vestergaard P, Emborg C, Støving RK, Hagen C, Mosekilde L, Brixen K. Eating disorders may affect bone health for years. Int J Eating Dis 2002; 32:301-308.

Sheri B. Doniger, DDS

Dr. Doniger has been in private practice of family and preventive dentistry for almost 20 years. She is currently focusing on women's health and well-being issues. She can be contacted at (847) 677-1101 or donigerdental @aol.com.