Editor's note: Originally published April 22, 2014. Formatting updated August 8, 2022.

A 29-year-old female presents to the office with a chief complaint of pain in the right side of her jaw that has progressively been getting worse over the course of the last two to three months. Her health history is noncontributory and she has fairly decent home care, as demonstrated by her lack of past dental needs.

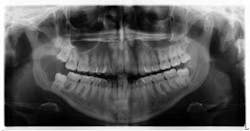

Clinical examination revealed inflamed tissue circa partially erupted No. 32 extending up to the distal of no. 2. The area intraorally was tender to palpation, but unremarkable extraorally. A panoramic X-ray was taken and a large radiolucent lesion was noted to extend from the distal of no. 1 to the distal of no. 32. A significant portion of bone destruction in the mandible was also observed. In addition, a radiolucency was seen distal to the crown on no. 17.

The patient was sent to surgery for enucleation and curettage of the lesion. Differential diagnoses included: unicystic ameloblastoma, odontogenic myxoma, and dentigerous cyst.

Let’s examine and review each of the differentials.

1. Unicystic ameloblastoma

- Benign neoplasm from residual epithelial components of tooth development

- Slow growing, locally aggressive, and can cause large facial deformities. Oftentimes will occur in a dentigerous cyst relationship

- Radiographically, lesions appear unilocular, well demarcated with a tooth present with in and around the radiolucency

- Removed via enucleation or marginal (block) resection

2. Odontogenic myxoma

- Aggressive intraosseous lesion, derived from embryonic connective tissue

- Primarily found in the premolar/molar areas of the mandible and distributed equally in the maxilla

- The slow, often painless growth and swelling will oftentimes displace teeth and not resorb the roots

- Radiographically appearances frequently consist of a “soap bubble” or “honeycomb” pattern

- Oftentimes will resemble an ameloblastoma

- Removed via local curettage or block resection

3. Dentigerous cyst

- Odontogenic cyst that surrounds the crown of an impacted tooth

- Oftentimes asymptomatic, but if large or inflamed, can produce swelling and pain

- Radiographically appears as a well-circumscribed radiolucency surrounding the crown of the tooth, oftentimes displacing it and adjacent teeth

- Removed via surgical enucleation; has a low recurrence rate

- Ameloblastoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma—different epithelial neoplasms that can arise in dentigerous cysts

Given the aforementioned differentials and their relationships, it is important to understand the full potential of these lesions. They are destructive and can be life threatening, especially if malignancy has occurred. Therefore, treatment and a definitive diagnosis must be rendered and obtained as soon as possible, as was the case for the patient described herein.

Our main concern was the extent of destruction—fracture potential and permanent paresthesia was extremely high. Following surgery, the patient was placed on a liquid diet for six to eight weeks. The specimen was sent to pathology. Diagnosis: dentigerous cyst. Follow-up over the course of the last year has proved to be promising—the bone has filled in, the patient has regained some feeling on the lower right side of her jaw and, thus far, there have been no recurrent or metastatic lesions observed. We are monitoring no. 17 and plan to remove it and the associated radiolucency when the bone has healed sufficiently in the right mandible.

Being astute and thorough with our clinical and radiographic examinations is vital to providing a comprehensive care approach when rendering care to our patients! The variability of intraoral and radiographic lesions demand that we be in tune to what “normal” and “not normal” pathology are. It is not unusual for the most benign looking lesion to be diagnosed as oral cancer of some kind! Finally, use all available resources—pictures (taken at one-, two-, and three-week intervals), radiographs, and clear documentation for reference and if needed, referral.

Reference

- Sapp JP, Eversole LR, Wysocki GP. Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. Mosby; 1997

About the Author

Stacey L. Gividen, DDS

Stacey L. Gividen, DDS, a graduate of Marquette University School of Dentistry, is in private practice in Montana. She is a guest lecturer at the University of Montana in the Anatomy and Physiology Department. Dr. Gividen has contributed to DentistryIQ, Perio-Implant Advisory, and Dental Economics. You may contact her at [email protected].