From whiter teeth to a better night's sleep: The case of orthodontics, occlusion, and overall health

This is the case of an airline pilot and former USAF fighter pilot who walked into a dental office with the goal of having "longer and whiter" teeth. From sleep apnea studies and orthodontics to restorative treatment and opening vertical dimension of occlusion, his goal was met—but even better, his overall health was positively impacted for life.

Editor's note: This article first appeared in DE's Breakthrough Clinical with Stacey Simmons, DDS. Find out more about the clinical specialties newsletter created just for dentists, and subscribe here.

CASE PRESENTATION: A 55-year-old male airline pilot and former US Air Force fighter pilot presented to our practice with severe wear into dentin throughout his entire dentition. He had been wearing a night guard for at least 20 years. He was aware of his grinding habit, but did not report any pain in his muscles. His joints could be loaded comfortably. He did not report any history of joint clicking, and there was no evidence of internal derangement. His point of initial contact in centric relation (CR) was 15/18.

Both teeth had been restored with porcelain-fused-to-metal crowns. The lower crown had lost all of the occlusal porcelain and was fractured down to the metal coping. He had more than a millimeter slide from CR to his maximum intercuspal position with 1 mm of mobility in tooth No. 10. We measured 4 mm of horizontal overjet with mild crowding on the mandibular anterior teeth (figures 1 and 2). He was within normal limits when evaluating his profile with Arnett's true vertical line, Rickett's E plane, and his nasiolabial angle (100 degrees). (1-3)

Figure 1: Before treatment

Figure 2: Before treatment

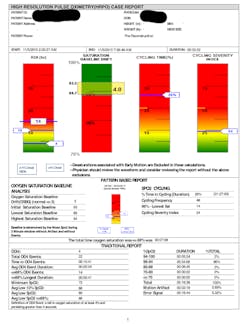

The patient failed all five of Dr. Peter E. Dawson's requirements for occlusal stability with multiple posterior interferences and poor anterior guidance. (4) He still has his tonsils, but does not report any snoring and is a Class II Mallampati. (5) His chief goal is for his teeth to be longer and whiter. Due to the erosive appearance of the teeth, we referred him to a gastroenterologist to test for GERD, which came back negative. Further, we had the patient evaluated by James Metz, DDS, and his team with a three-night at-home high-resolution pulse oximeter (HRPO) to test blood oxygen saturation levels (SpO₂) preoperatively, screening for potential sleep apnea with associated bruxism (figure 3). (6)

Figure 3: Sleep study screening pre-reconstruction

The treatment plan

Due to the patient's excessive overjet, mandibular crowding, and a V-shaped maxillary arch form, we recommended orthodontic repositioning before completing the patient's restorative treatment. He elected to use Invisalign orthodontics. Treatment would align and procline the lower anterior teeth, bodily move teeth Nos. 8 and 9 lingually, and round out the maxillary arch. Orthodontic treatment was completed in 10 months. Next, we took a new set of diagnostic models and mounted them in CR.

The goal of restorative treatment was to establish centric holding stops on all of the patient's teeth in CR and establish a shallow anterior guidance in harmony with the envelope of function, which would disclude all of the posterior teeth in excursive movements. The patient's lower anterior occlusal plane was concave, so those teeth were built up in the wax-up. In addition, there was no tooth display at rest, so we lengthened the maxillary incisors by about 1.5 mm, improving the width-to-length ratio to 80%. (7)

Testing the provisionals

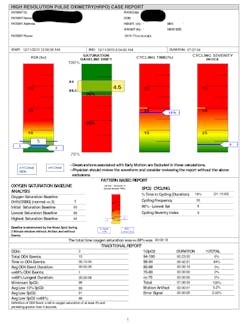

While in provisionals, the patient was evaluated with a second home sleep study. According to Dr. Metz, there was significant improvement in the patient's overall health, including his heart rate and 50% fewer intermittent hypoxia events (figure 4). The number of intermittent hypoxic events has been shown to impact overall health negatively by increasing inflammation through the release of cortisol. (8) The vertical component probably contributed most to this positive change in health, allowing more room for the tongue to move forward in the mouth and open the airway, combined with carefully created provisionals that were not thick and bulky.

Figure 4: Sleep study screening with provisionals

After two months and careful evaluation in the patient-approved provisional restorations, this case was completed. The patient was restored completely (except for two acceptable implant crowns on tooth Nos. 19 and 20) with full-zirconia crowns on the posterior teeth and zirconia with minimal facial layering on the anterior teeth. He has been successfully restored for two years (figures 5 and 6) to date.

Figure 5: After treatment

Figure 6: After treatment

Final thoughts

With carefully planned treatment, we can give patients not only an esthetically pleasing and properly functioning smile, but we can also positively impact their overall health.

References

1. Arnett GW, Jelic SJ, Kim J, et al. Soft tissue cephalometric analysis: diagnosis and treatment planning of dentofacial deformity. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop.1999;116(3):239-253.

2. Ricketts RM. Esthetics, environment, and the law of lip relation. Am J Orthod. 1968;54(4):272-289.

3. Elias AC. The importance of the nasolabial angle in the diagnosis and treatment of malocclusions. Int J Orthod. 1980;18(2):7-12.

4. Dawson PE. Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Occlusal Problems. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby; 1974.

5. Mallampati SR. Clinical sign to predict difficult tracheal intubation (hypothesis). Can Anaesth Soc J. 1983;30(3 Pt 1):316-317.

6. Okensberg A, Arons E.Sleep bruxism related to obstructive sleep apnea: the effect of continuous positive airway pressure. Sleep Med. 2002;3(6):513-515.

7. Sterrett JD, Oliver T, Robinson F, Fortson W, Knaak B, Russell CM. Width/length ratios of normal clinical crowns of the maxillary anterior dentition in man. J Clin Periodontol. 1999;26(3):153-157.

8. Meerlo P, Sgoifo A, Suchecki D. Restricted and disrupted sleep: effects on autonomic function, neuroendocrine stress systems and stress responsivity. Sleep Med Rev. 2008 Jun;12(3):197-210. doi: 1016/j.smrv.2007.07.007.

For more articles about clinical dentistry, click here.

Editor's note: This article first appeared inDE's Breakthrough Clinical with Stacey Simmons, DDS. Find out more about the clinical specialties newsletter created just for dentists, andsubscribe here.