Ever wish you had a template for your toughest cases? Dr. Ari Forgosh explains how to simplify even the most difficult dental cases into a series of steps with a little extra planning and forethought. He outlines a treatment plan that will reproduce predictable results for complex cases and increase case acceptance.

Editor's note: This article first appeared in Breakthrough Clinical, the clinical specialties newsletter created just for dentists. Browse our newsletter archives to find out more and subscribe here.

It was the summer of 2012, and I was eager to show off my new CAD/CAM restoration system (CEREC). I had one patient in particular who I knew would be impressed with this technology. “Joel” held several hundred patents, some of which you use every day, and he hinted that he spent the 1940s “in the neighborhood” of the Manhattan Project.

There are smart people in the world, but Joel was truly next-level genius. I was certain he would be fascinated with CAD/CAM dentistry, but instead of being in awe, he claimed that it was really quite simple. When I pressed him about this, he explained that all complex systems are actually just a series of simple concepts. The genius, he told me, lies in finding a valuable application and being able to assemble the steps in the right order. The same can be said about complex dental treatment plans.

A well-developed treatment plan in dentistry can be viewed as a series of simple steps that follow a logical progression. In practical application, DENTISTS WHO COMPLETE TREATMENTS IN STAGES can increase case acceptance, improve patient experience, and make the entire case—and each step of the journey—easier and more predictable.

The pathway to a predictable treatment plan

As with most projects, we must begin with the end goal in mind. In dentistry, that means developing a treatment plan prior to starting any treatment. In my practice, we use a process that allows us to simplify our treatment plans and produce predictable outcomes. The process we use is based on the systematic approach pioneered by Dr. Peter Dawson, founder of The Dawson Academy. Any dentist can properly diagnose even the most complex dental problems by following this method. In this article, I will outline our plan in a series of simple steps to develop a structured treatment plan that you can follow to reproduce similar plans with predictable results for your complex cases.

A thorough clinical examination designed to discover both functional and biological problems is critical to this approach. Through the exam, we are able to:

- Determine the health and position of the temporomandibular joints,

- Check the muscles of mastication for symptoms of disharmony, and

- Look for any signs of occlusal instability (wear, mobility, and migration).

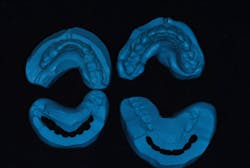

We take a full series of photographs and use a facebow to mount high-quality study models on a semiadjustable articulator in centric relation. Once we have this data, we can begin the treatment-planning process.

As we develop a treatment plan, we do the case four times: (1) in our minds, (2) in wax, (3) in provisionals, and (4) in porcelain.

This first pass on the case is called a “2-D analysis,” because we primarily use the patient’s photos to develop our treatment objectives. Each of these photos shows us something specific that we will apply to our visualization of this patient’s ideal smile.

After the 2-D analysis is completed, we will have established:

- A vertical and horizontal incisal edge position

- Gingival margin contour

- Whether the buccal corridor is sufficiently filled

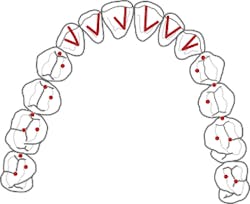

We will also have started to develop a plan for the best approach to achieve each objective. Once the plan is finalized, we’re ready to move on to wax and translate that mental image into a 3-D reality using wax and stone. There is a specific sequence to this process:

- Establish the lower incisal edge position in harmony with the plane of occlusion.

- Build the upper incisal edges to the position derived from the 2-D analysis.

- Place the models on the articulator and complete the wax-up to provide equal intensity stops on all teeth, with anterior guidance that prevents posterior interferences in all directions of mandibular movement.

Throughout this process, we can determine if we need to increase the vertical dimension of occlusion, and discover the best way to balance the occlusion either by selective reduction or restoration of teeth. Our goal is always to do the least amount of dentistry necessary to get the best results.

Before we start prepping teeth, we have to be certain that our foundation is sound, which means establishing biologic health, including addressing periodontal concerns and caries control.

Next, we are ready to transfer the information from the wax-up to the mouth using a series of putty stents and guides to fabricate the provisional restorations (more details are listed below). During this step, we work out the finer details of design using phonetics and arc of closure to refine edge position and lingual contour.

Once the patient is completely comfortable and happy with the provisionals, we take a new set of photos, facebow, bite registration, and models to communicate with the ceramist, who will complete the fourth version of the case—in porcelain.

5 tips for successful sequencing

Dentists often have to sequence more complex treatments because of time, finances, and other factors. How can we sequence treatment in a way that allows the patient to function between phases? How can we approach this complex system as a series of simple steps?

Here are five tips for developing a predictable treatment sequence:

1. Each appointment should end with a balanced occlusion in centric relation. This keeps your patient comfortable, prevents broken provisionals, and allows for long-term phasing of larger cases.

2. Use appropriate putty matrixes for your mock-ups and provisionals. This step transfers the wax-up to the mouth. When making your matrices, use the models that match the current stage of treatment. For example, if you are restoring the lower arch but haven’t yet restored the upper, adapt the putty around the wax-up of the lower model. Then, with the articulator locked in centric relation, close the original upper model into but not through the unset putty. This creates an index of the opposing teeth.

When you transfer your wax-up to the mouth, load the self-curing provisional material in the putty, seat it fully in the mouth, and have your patient gently close into the index. Having your patient hold the matrix like this assures that it is seated correctly. An added bonus is that having your patient rest on the putty in centric relation deprograms the muscles, making it easier to adjust the jaw into the desired position.

3. Do a mock-up and equilibrate before prepping; double-check your reduction with a guide. The mock-up helps you and your patient visualize the intended results before taking an irreversible step. It also lets you make your depth cuts from the final contour, rather than the existing shape of the teeth. Doing a rough equilibration at this point makes the provisional stage much easier. Remember, the mock-up is a duplicate of your planned results.

4. Idealize the lower arch first, when possible. The lower incisal edges determine the position and lingual contour of the upper anterior teeth, so this is the best place to start. These initial restorations can be done with provisionals, composite resin, or porcelain, depending on the scope of work to be done, financial considerations, and the phasing of your plan.

5. Make necessary occlusal adjustments on the opposing arch once the first arch is idealized. The mock-up and provisionals are the blueprints for the final restorations, determined before ever picking up a handpiece. Once these are transferred to the mouth, make your adjustments to the opposing arch to provide a balanced occlusion for this treatment phase. This way, when you restore the second arch, your occlusal stops will already be established. You will still need to adjust the upper incisors for proper phonetics as well as horizontal and vertical position. Proper treatment planning gets us close to the ideal position, but there is no substitute for seeing the provisionals in the mouth.

Conclusion

With proper planning and forethought, even the most complex cases can be broken down into a series of simple steps. It all starts with a complete exam and diagnosis, followed by a properly developed plan that meets the patient’s goals and the requirements for a stable occlusion.

Once we have a finished wax-up of our treatment objectives, we can make a series of putty matrices and reduction guides to be used in a thoughtful, sequential manner to transfer our plan to the mouth. By taking a programmed approach, it is possible to eliminate guesswork and introduce predictability in even the most complex of cases.

Author's note: To learn more about this treatment planning protocol and more, I recommend reading Functional Occlusion from TMJ to Smile Design, by Peter E. Dawson, DDS, and getting a front-row seat for The Dawson Academy’s lecture, Functional Occlusion—From TMJ to Smile Design. From this course, you will learn how to consistently develop predictable solutions to the most complex dental problems.

Editor's note: This article first appeared in Breakthrough Clinical, the clinical specialties newsletter created just for dentists. Browse our newsletter archives to find out more and subscribe here.