A Review of Dental Negligence

During the past 12 years, I have been asked to evaluate 242 medical legal cases for dental negligence. The majority of them had unfortunate results to which patients attributed malpractice. The purpose of this article is not to assess the merit of these litigations, but to educate dental practitioners about the types of treatment which may result in a greater incidence of legal claims, so they will be better prepared to avoid them.

No. 1 negligence: extractions

In the infection requiring hospitalization subset, all patients were hospitalized, and of these, eight patients died from the infections. In the severed nerve subset, the injuries were permanent and the dentists involved did not refer or follow up the nerve injuries. In the sinus perforation subset, the dentists neither diagnosed nor referred the patient for treatment of the perforations. One perforation was due to a bur perforating the sinus. The bur fractured and was left in the sinus with no referral or attempt at retrieval. Lack of diagnosis and treatment also existed with the mandibular fractures and TMJ injuries. Of the defendants, 51 were general dentists and 12 were oral surgeons.

No. 2 negligence: endodontic procedures

The second most common alleged negligence was due to endodontic procedures. Of the above negligence claims due to endodontic procedures, all of the defendants were general dentists. The complications included instruments left in canals, nerve and sinus perforations, air embolisms, and life-threatening infections, including four fatalities. Of the life-threatening infections, seven were due to brain abscesses, and one due to osteomyelitis. Of these eight infections, four were fatalities and four resulted in irreversible brain damage.

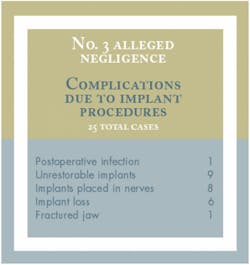

No. 3 negligence: dental implants

In the implant loss subset, two to 10 implants were lost, and treatment planning was alleged to be deficient to non-existent. The patient with the post-operative infection succumbed to the infection. In 24 of the negligence claims involving dental implant surgery, the defendants were general dentists, and one was a periodontist.

No. 4 negligence: substandard crown, bridge treatment.

It is difficult to categorize this group into subsets because most of the treatments included numerous complaints including open margins, overhanging restorations, and poor occlusion. All cases involved multiple units or "full-mouth reconstructions." There was a universal lack of treatment planning in these cases. All defendants were general dentists.

No. 5 negligence: periodontal disease

There were 19 cases of failure to diagnose or treat periodontal disease in a timely fashion. All defendants were general dentists. In the majority of these cases, X-rays were not taken routinely, and periodontal probings were rarely or never recorded.

No. 6 negligence: orthodontics

There were 18 total cases of orthodontic treatment complications and 14 cases in the subset of root resorption. Numerous teeth per patient were seriously affected and the majority of these teeth were lost. Radiographs were not routinely taken. Of the treating dentists in the category, six were orthodontists and 12 were general dentists. The remaining four cases involved TMJ injury.

No. 7 negligence: dental anesthesia complications

This category tied with extractions for the most fatalities. There were 12 claims with eight patient fatalities. Of the eight deaths, three were children. Of the defendants, four were oral surgeons, two were pedodontists, and six were general dentists.

No. 8 negligence: dental infections

There were 11 malpractice claims under this category. The infections resulted in four fatalities, two brain abscesses, and one case of septic arthritis. Nine defendants were general dentists, and two were oral surgeons.

No. 9 negligence: dental injections

Of these 10 cases, seven affected the lingual nerve; three involved the inferior alveolar nerve. In all cases, the dentists allegedly were made aware they had hit the nerve, but did not withdraw the needle and reinject as suggested in dental literature. In addition, the dentists neither followed up the injuries nor referred them to be followed. Seven defendants were general dentists, and three were oral surgeons.

No. 10 negligence: adverse drug reactions

In all five cases, the drug administered was contraindicated by the patient's medical history. There were two fatalities in this category. One defendant was a periodontist; the other four were general dentists.

TMJ and orthognathic surgeries

There were four cases each of TMJ and orthognathic surgeries alleged to be substandard. All surgeries needed follow-up corrective surgery. All patients had permanent injuries. All defendants were oral surgeons.

Oral cancer

There were four cases of alleged failure to diagnose oral cancer in a timely fashion. Two patients did not survive. Two defendants were oral surgeons; two were general dentists.

Miscellaneous incidents

The last group of six incidents is difficult to categorize. There were two serious drill injuries, one undiagnosed needle fracture, one undiagnosed x-tip fracture, Benadryl injected into the inferior alveolar nerve, and Lidocaine injected into the patient's eye. All cases resulted in permanent injuries to patients involved.

What can be learned from this survey?

The majority of alleged cases also lacked proper informed consent and referral protocol. Of suits brought against defendants for broken instruments left in canals, there was no documentation that patients were advised of the broken instruments, nor were patients referred to specialists after the incidents.

The majority of the 242 cases were filed against general dentists, and of these cases, most were filed in the disciplines of oral surgery (extractions) and endodontics.

In my survey, 11 of the defendants were female general dentists and one defendant was a female oral surgeon. This represents 5 percent of the total suits — a relatively small number compared to the percentage of women practicing dentistry.

In the oral surgery category, all general dentists who were alleged negligent were sued due to extraction complications. Some general dentists are comfortable performing extractions. Some have additional surgical training, while others have extensive extraction experience. Nevertheless, each tooth must be evaluated individually. A diagnostic X-ray that shows all roots and surrounding anatomy is imperative. Potential complicating factors include hooked or curved roots and proximity to nerves and sinuses. Such cases are generally best referred to oral surgeons. If a dentist underestimates the difficulty of an extraction and a complication occurs, the patient should be advised. Patients should be carefully followed or referred to an oral surgeon.

Endodontic treatment resulted in the second highest number of malpractice claims against general dentists. Like extractions, teeth that need to be treated endodontically should be evaluated for curved roots, calcified canals, and other potential complicating factors. Good pre-operative X-rays and use of a rubber dam are imperative. Infections due to endodontic procedures can be deadly due to their anaerobic nature. If a dentist breaks an instrument in a canal and the instrument cannot be retrieved, the patient should be advised and referred appropriately. The most glaring area of alleged negligence in the implant procedure category was failure of treatment planning or improper evaluation of the patient or both. Because implants are permanent, they must be placed in a site suitable for restoration. When they are placed in locations that cannot be utilized, patients frequently will attempt to sue the dentist who placed them. Evaluation of the patient should include the history of smoking and systemic diseases that can affect healing and bone density.

The majority of orthodontic lawsuits were due to severe root resorption. Patients must be X-rayed routinely to check for root pathology. If root resorption occurs, the patient should be advised immediately. Treatment may need to be modified or ceased. Adult patients tend to lose bone more rapidly than younger patients during orthodontic treatment and should be monitored closely.

As stated previously, most of the crown and bridge litigation involved multiple units or full-mouth reconstructions. Again, treatment planning these cases is imperative. Diagnostic wax-ups should be routine, and temporaries should reflect the permanent crowns to avoid cosmetic disputes and functional problems with the final product.

To avoid suits regarding failure to diagnose periodontal disease, keep periodontal records. It is not necessary to do probings on a patient who comes in for emergency treatment, but if that patient becomes a "regular" patient, probings must be done and recorded routinely. Dental X-rays also should be routine. If a patient refuses, document it in the chart. Patient referrals also should be documented by placing a copy of the referral slip in the patient's chart.

Although there were 11 cases in the "failure to treat dental infections in a timely fashion" category, a significant number resulted in infections that required hospitalization. Of those cases, 58 were smokers — yet many times a history of smoking was not taken by the dentist. A smoking history should be a red flag for patients who are more prone to infections and complications.

To avoid suits due to dental injections, inject slowly and monitor your patient during the procedure. Tell the patient to raise his or her hand if there is an "electric shock." If the patient indicates you have hit the nerve, withdraw the needle and carefully reinsert from another direction after gaining the patient's permission. Permanent nerve injury and trigeminal neuralgias can occur from routine dental injections.

Communication failure

A breakdown of communication was apparent in many of the claims filed. In a majority of the crown and bridge suits, patients alleged they would have never sued had the dentist refunded their money. Patients felt "blown off" by the front desk and ignored by staff. The low percentage of female dentists being named in litigation may be because women often have better communication skills and may be willing to take more time explaining procedures and complications to patients. They also may be more willing to refer difficult cases.

This survey is not proposed to be representative of most dental suits or of dental treatment as a whole. Most dentists practice entire careers without becoming defendants in litigation. However, to my knowledge, none of these cases has been reported in any study or scientific published paper, leading to the conclusion that serious injuries due to dental procedures may be under reported.

Although I am not an attorney and cannot claim to have special credentials to give other dentists legal advice, others can benefit from my experiences. Evaluate each case carefully and refer those cases which appear to have potential complications. Document everything — especially all patient refusals of treatment. If someone threatens to sue, contact your malpractice carrier immediately. They will refer you to a defense lawyer who usually has experience defending dentists and will be familiar with the dental terminology and treatment. If you do not feel comfortable with that attorney, ask your insurance carrier for another one.

Crystal Baxter, DMD, MDS

Dr. Baxter is a "wet-gloved" practitioner in a private prosthodontic practice in Chicago. She received her DMD, certificate of prosthodontics, and Masters of Dental Science degrees from the University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine. Reach her at [email protected].