Some dental schools still teach that the root canal should be obturated to the radiographic apex, and anything short of that is unacceptable. The reality of the situation is a little more complex.

This article first appeared in the newsletter, DE's Breakthrough Clinical with Stacey Simmons, DDS. Subscribe here.

Knowing where the root canal ends is a very important fact to be aware of during the course of endodontic procedures. It determines how far we instrument the canal and where we place the root canal filling material. In turn, this will often affect the success of the root canal treatment. Currently, there seems to be some difference of opinion on this subject. Some dental schools still teach that the root canal should be obturated to the radiographic apex, and anything short of that is unacceptable. The reality of the situation is a little more complex.

We start to get a clue about what is going on with the publication by Imura et al. in 2001, in which the authors show in 2,000 endodontically treated teeth that those with short filling levels had a higher success rate than teeth with filling material to or in excess of the apex. (1) Schaeffer et al. confirmed this finding in 2005 in their publication. (2) Their meta-analysis indicated that a better success rate is achieved when treatment includes obturation short of the radiographic apex.

This begs the question that if short is better, how short of the radiographic apex do you want to be? Luckily there is a lot of published literature to guide us. Kojima et al. stated in their research that the root canal should be filled to within 2 mm of the radiographic apex. (3) Ng et al. reported that several factors, including root filling extending to 2 mm within the radiographic apex, were found to significantly improve the outcome of primary root canal treatment. (4) In a study by Peak, Bryant, and Dummer, root fillings placed using cold lateral condensation of gutta-percha to within 2 mm of the radiographic apex of the tooth were associated with the best outcomes. (5) Chanda reported that several factors significantly favored endodontic success, one of which was the root filling extending to 2 mm within the radiographic apex and not beyond. (6) In a large study of 1,290 root canal teeth, Gomes et al. reported that canals filled up to 0 mm to 2 mm short of the apex had a significantly higher number of teeth rated as healthy, compared with overfilled or underfilled cases (P=.001). (7) In all of these studies and quite a few more, the key number for a higher success rate seems to be a root canal filling ending between 0 mm to 2 mm short of the radiographic apex.

READ MORE |Endodontic insight: Optimum endodontic irrigation techniques

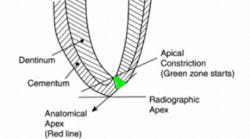

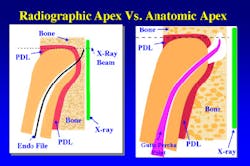

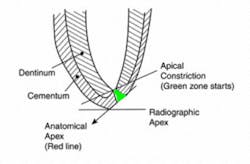

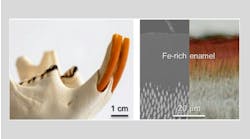

The next question we should ask is why is 2 mm the key number? For years, many clinicians stated as fact that the anatomic apex was located 0 mm to 2 mm short of the radiographic apex in 50% of the teeth. Therefore, if you filled to the radiographic apex 50% of the time, the gutta-percha would be overextended. Usually, this overextension of gutta-percha means that it is now situated in the periodontal ligament or alveolar bone, or both (figure 1). Gutta-percha extending into these structures generally will cause some amount of pain and lead to an unsuccessful root canal treatment (figure 2).

Figure 1: Using only an x-ray to determine working length (WL), the anatomic apex is 0 mm to 2 mm short of the radiographic apex. The illustration on the left is an overextended instrument, which shows as at the radiographic apex on the x-ray. The illustration on the right shows gutta-percha in the ligament and bone due to faulty WL to the radiographic apex.

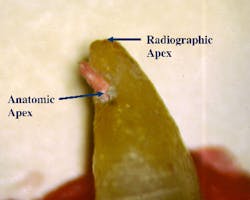

Figure 2: Gutta-percha short of radiographic apex but long on anatomic apex. This is a common cause of postop and continued endodontic pain.

Recently, El Ayouti et al. published an article that confirms all the others. The authors stated: “The foramen (anatomic apex) was short of the apex (radiographic) in 88% of the canals, and in 5% of the canals the foramen was more than 2 mm short of the apex, showing that root fillings extending to the radiographic apex are actually overfillings in most of the canals” (figure 2). (8)

All of this research tells us that in order for a root canal to have a higher success rate and not be painful to the patient, the gutta-percha filling should look short of the radiographic apex. Thus a root filling ending at the radiographic apex is no longer the ideal goal. On the radiograph the gutta-percha should appear to be 0 mm to 2 mm short of the radiographic apex.

How can we reliably achieve this on a consistent basis? There is only one answer to this question and that is with modern electronic apex locators. The apex locator is the only instrument that allows us to locate the constriction accurately. If we use the constriction as the working length, our obturation will not impinge on the periodontal ligament or surrounding structures. Our endodontic success rate will go up (figure 3). This means less post-operative pain for your patients and a better and faster healing tooth.

Figure 3: The instrumentation and root filling should terminate in the green zone. This is anywhere between the constriction and the anatomical apex.

References

1. Imura N, Kato AS, Zaia AA et al. Success evaluation of 2,000 endodontically treated teeth. J Endod. 2001;27(3):234 Abstract PR11.

2. Schaeffer MA, White RR, Walton RE. Determining the optimal obturation length: a meta-analysis of literature. J Endod. 2005;31:271-274.

3. Kojima K, Inamoto K, Nagamatsu K et al. Success rate of endodontic treatment of teeth with vital and nonvital pulps. A meta-analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004:97(1):95-99.

4. Ng YL, Mann V, Rahbaran S, Lewsey J, Gulabivala K. Outcome of primary root canal treatment: systematic review of the literature–part 2. Influence of clinical factors. Int Endod J. 2008;41(1);6-31.

5. Peak JD, Hayes SJ, Bryant ST, Dummer PM. The outcome of root canal treatment. A retrospective study within the armed forces (Royal Air Force). Br Dent J. 2001;190(3):140-144.

6. Chandra A. Discuss the factors that affect the outcome of endodontic treatment. Aust Endod J. 2009;35(2):98-107. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2009.00199.x.

7. Gomes AC, Nejaim Y, Silva AI et al. Influence of endodontic treatment and coronal restoration on status of periapical tissues: A cone-beam computed tomographic study. J Endod. 2015;41(10):1614-1618. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2015.07.008.

8. ElAyouti A, Hülber-J M, Judenhofer MS et al. Apical constriction: location and dimensions in molars–a micro-computed tomography study. J Endod. 2014;40(8):1095-1099. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.12.002.

This article first appeared in the newsletter, DE's Breakthrough Clinical with Stacey Simmons, DDS. Subscribe here.