The reality of working with kids

Believing each child will have an "ideal visit" sets the stage for pediatric success

By Greg Psaltis, DDS

When my fellow dentists discover that I am a pediatric specialist, it is not unusual for them to express either amazement, pity, or, at times, incredible gratitude that I "do what I do." I always marvel at the misconceptions about my specialty and find amusement in the usual image that it evokes for other dentists — a day full of out-of-control screaming monsters, vomiting and struggling from 8 a.m. until 5 p.m. According to the feedback I hear from my peers, it's as if they view pediatric dentistry as a neverending wrestling match with alligators in piranha-infested waters! This couldn't possibly be farther from the reality of working with children. In fact, most visitors who come to observe my practice invariably comment on the calmness of the office in spite of 50 or so patients being seen in a normal, non-hectic way. Of course it helps to have a team of talented professionals — both assistants and a restorative hygienist. My team consists of 15 women who make my job remarkably easy. However, the cornerstone of the practice still evolved from one simple tenet — we believe each child will have an ideal visit each time he or she comes to see us. When the mindset is positive and the operator's belief system is based on the conviction that the outcome for the patient will be both successful and safe, treatment of the young patient becomes not only simple, but also gratifying far beyond the remarkable fiscal rewards that accompany the care.

To be certain, there are "tricks of the trade," but if that first essential piece is not firmly entrenched in the mindset of the providers, there is no way for "cute" terminology, reasonable treatment planning, judicious sedation, or distraction techniques to overcome the negative assumption that "children are a problem." In my experience, I have found that children (who usually don't have any expectations) are far easier to treat than adults who have often made up their minds about dentistry, how they relate to it, whether or not it will be "painful," and a myriad of other attitudes. By capturing a child in an unbiased state, we can create a positive first experience and thereby set the tone for all future dental visits. This is a function of the doctor's attitude, plus appropriate use of skills that will enable all parties to have a mutually fulfilling and successful visit.

Critical elements for success

It is beyond the scope of this article to enumerate all the facets of behavior management of a child patient, but the elements that I feel are critical to the successful presentation of dental care to a young child are as follows:

Use terminology that is age-appropriate and positive — In our practice, we don't give "shots," we "put teeth to sleep." We don't feel this is deceptive. It is descriptive and avoids labels for which the child may have previous experience and, therefore, negative connotations. By giving the child an accurate expectation, we create a bond of trust when our description matches the experience. When we tell a child her lip will start feeling fat and then it does, the child learns that she can trust us.

Explain everything — One of the most effective distraction techniques is to provide a running commentary to the child so that nothing comes as a surprise. By telling the patients (in simple, understandable words) what is happening, they can anticipate the next instrument, sensation, or procedure with minimal anxiety.

null

Focus on what is going well — Don't be phony about it and don't sugar-coat it, but keep your attention on the aspects of the appointment that are working. Be specific in your feedback to the child. Avoid general statements like, "You're being a good helper" because the child may not even understand what she is doing right. Be clear by saying, "It is very helpful when you hold your mouth open because I can see better," or "When you keep your head still like that, I can work more quickly." This provides definite teaching to the child so that she will better know how to help you.

Keep appointments short — This is somewhat dependent on age, but we rarely have restorative visits that are longer than 45 minutes to an hour unless they are accompanied by sedation.

Avoid pain — While some practitioners I have met often treat primary teeth without local anesthetic, we routinely use it for a number of reasons. We do not know ahead of time whether or not the child will experience discomfort with a "routine" procedure. I have seen many children maintain that a rubber cup for a prophy is agonizing while other children will sit through multiple extractions, pulpotomies, stainless steel crowns, etc., and never say a word. I am unable to determine which children will have a pain-free visit for a given procedure, so I prefer to anesthetize to ensure comfort. We use topical anesthetics and nitrous oxide when indicated to ease the injection process, but do not routinely encounter responses to the actual procedure.

Rubber dams are routine — This affords a better view, keeps debris from falling into the child's mouth and provides a more controlled field in which to place the compomer materials that we use for primary posterior teeth. When doing primary root canals (pulpectomies) and/or stainless steel crowns, it also affords us the safety of nothing being dropped into patients' mouths and potentially being aspirated. Having the appropriate clamps is essential for successful dam placement and retention.

What about the parents?

It goes without saying that one of the more controversial aspects of pediatric dentistry has to do with the parents. There is an enormous range of thought on this topic, but it is my opinion that the "misbehaving" parent (that is, the one who causes more problems than solutions) is behaviorially similar to the child — they simply don't know what is expected of them unless told. With the legal atmosphere being as it is these days and parenting philosophies spanning such a broad range of possibilities, it is my belief that having informed parents present is safer for the practitioner.

Here are some critical elements for having parents be an asset and not a liability in your practice:

- Explain your philosophy in specific terms, including the management tools you will employ in treating the child, the child-friendly terminology you will use, and the role you expect the parents to play in the appointments.

- When the parents accompany the child into the operatory, tell them up-front that it is important for you put your entire attention on the child. Tell them you expect the child to listen to you and not to the parents. In support of this, the parents must be informed that they are not to speak to the child.

- Ask the parents for their support of the practice's terminology. Give them a sheet with sample words so that they will not inadvertantly frighten their child with words or phrases like shot, drill, yank a tooth, or other negative images.

- Advise the parents to not prepare the child for the restorative visit. I manage this by explaining to the parent that I will prepare the child literally on the spot. I do this by making direct eye contact with the child, explaining that during my examination that I found "x" number of "sugar bugs" and that I will make them go away at the next appointment. I then ask the child if she can help me at that visit in the same way she did for the checkup. In virtually every case, the child will agree to this. I then tell the parent that the preparation is complete.

- Be realistic about your expectations about the child's next visit. If you believe that the child will not handle the visit easily, it is unwise to tell the parent that you expect everything to go smoothly. Parents know their children better than you do and most come into the dental setting with low expectations about how the child will do. You are far better off being clear and honest.

Obviously there are many tools that facilitate a successful pediatric dental appointment. I have found that placing my focus on the behaviorial side of dentistry has provided as much satisfaction for me as the purely technical part. It must be a "given" that excellent technical dentistry must accompany the management. My experience has taught me, though, that if a child is misbehaving, it becomes an extreme challenge to provide the high quality of care to which dentists strive. In this way, I view management as a critical aspect of proper dental care for young patients.

Dr. Gregory Psaltis has been in private pediatric dental practice in Olympia, Wash., since 1981. In addition, he has lectured nationally and internationally on a variety of topics, both clinical and business. He is actively involved in consulting with other offices to create more enjoyment and profit in the workplace. His Web site is www.psaltis.info or he can be reached by phone at (360) 413-5760 or e-mail at [email protected].

Pediatric anesthesia and rubber dam

Not every dentist who treats children would agree with the necessity of local anesthesia and/or rubber dam for restorative care. We routinely use both in my practice, largely because we believe they enable us to provide better restorations painlessly, particularly in this age of bonded restorations. The materials and products we routinely use include the following:

Topical anesthetics — One Touch produced by Hager. This product contains 18% benzocaine and 2% Tetracaine HCl. We use this routinely for our pre-injection topical anesthetic and have begun using it as an all-purpose topical anesthetic for multiple tasks. It is slightly objectionable to taste, but very effective and profound in use. Other topical anesthetics are used for narrowly defined tasks, but One Touch is now our standard.

Local anesthetics — 2% Lidocaine HCl with 1:100,000 epinephrine produced by Cook Waite. This is our routine local anesthetic, used in most restorative cases that require reliable anesthesia for any extended period of time. We like its reliability, safety, and duration. 3% Carbocaine (Mepivacaine HCl) produced by Cook Waite. This is our first alternative for patients allergic to lidocaine. 4% Articaine HCl (Septocaine) distributed by Septodont. We use this when patients have a history of lidocaine not being effective. We have found that it is particularly effective in anesthetizing second molars in teenage patients. I have spoken with some dentists who are using this routinely for all local anesthesia.

Local anesthetic techniques — For most routine procedures, we use classic infiltration and mandibular block techniques. When the procedure is limited to a single primary tooth in the mandible, we have excellent success with mandibular infiltration anesthesia. We often use 30 gauge extra short needles made by Acuject, which we find to provide adequate depth of penetration and nearly painless initiation. Others have enjoyed excellent results with intraligamentary injections. A variety of syringes are available for this technique.

Rubber dam — Medium latex 5"x 5" rubber dam (Ivory) distributed by Heraeus Kulzer. This is our usual choice. We find it to be very pliable, yet strong. Flexi-dam 150mm x 150mm produced by Roeko. This is a non-latex rubber dam that is in nearly every way as effective as the latex, other than a slightly lower degree of stretchability.

Rubber dam clamps — Ivory 8A, 14A, 2, 3, 12 and 13. For most of our primary tooth care, we find 8A clamps to be very effective. The 14A is extremely effective on partially erupted permanent teeth. The 2 and 3 are good for fully erupted permanent biscuspids and molars, and the 12 and 13 (which have one fluted wing) are less invasive to the gingival tissues and often adequate to stay on partially erupted teeth.

-- Dr. Greg Psaltis

A hygienist's view of children

It is said that first impressions are lasting. As a dental hygienist, this is a phrase I always try to remember when reaching out to young children. I have learned over the years that, for some children, fear of the unknown is often the greatest fear of all. When a small child comes into the office, especially if this is his or her first dental visit, my main objective is to make this experience as wonderful as possible.

There are certain guidelines I try to follow, but I feel there are no rules set in stone when it comes to dealing with children. Every child and every situation is so unique that I try to be as flexible and compliant as possible. I feel that kindness is essential and that patience goes a long way in earning the trust and respect from a pediatric patient. In most cases, I never object to a parent being with the child during treatment. Having Mom or Dad present often gives the child a sense of security and support.

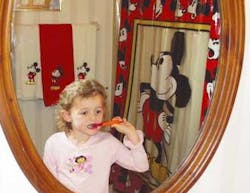

Children love to receive gifts, so I usually begin by letting them choose a new toothbrush and some floss to take home with them. Some children are ready to sit in the treatment chair and others are very frightened of it. By first showing them the buttons on it go up and down, or back to a horizontal position, they are made aware and there are no surprises with movement. I try to explain and show them everything I will be doing — before I do it — in an effort to escalate their comfort level and eradicate any fears they may have.

Some initial visits consist of only a ride in the chair and perhaps counting their teeth. I always try to praise them for their efforts and remind them that they were the "best" patient I had seen that day. With children under the age of six, I always encourage independent brushing, but let them and their patients know how important it is that one of the parents brush the child's teeth thoroughly once a day and helps with flossing. I also encourage the use of fluoride rinses at bedtime to strengthen the enamel and make the teeth more resistant to decay.

Another topic I like to discuss with children and their parents is diet. It is important to avoid foods and liquids high in sugar and those that are sticky and retentive on the tooth surface. Foods like hard, crunchy fruits and vegetables which promote saliva flow, as well as popcorn and peanuts are better choices for snacks. Foods that contain sugars are better eaten with a meal, rather than in between meals. Many times it is the frequency rather than the amount of a sugared snack that is more damaging to the enamel.

Working as a hygienist over the past 20 years, I have had the privilege of working with some wonderful dentists who have taught me a great deal about dealing with small children. I worked for several years with Dr. Michael Glinka, a pediatric dentist in Maumee, Ohio. He demonstrated such patience and kindness toward his patients, offering praise and a positive outlook in almost any given situation. Not only was he exceptional with children, but he also displayed a genuine compassion for many of the handicapped patients we saw. Being the mother of a son who is both mentally and physically impaired, I learned a great deal from Dr. Glinka on special techniques that proved effective when working with these special-needs patients.

Eight years ago, I began working in the dental office of Drs. Charlick, Springstead, and Wilson Dental Associates in Brighton, Mich., where I am presently employed. Although we are not a pediatric practice, we see a large number of children and special-needs patients. In February — "Children's Dental Health Month" — many of our staff members visit more than 3,000 children in area schools, teaching and promoting dental education. Our efforts are focused on making these visits fun and informative.

One story I would like to share with you is that of a young mother whose son is severely handicapped. After being shuffled from one dental office to the next, she found herself in our office. Almost pleading, she wanted to know if anyone would be willing to help her son. Due to several medications, her son's gingival tissue was irritated and severely enlarged. He also presented with moderate calculus on more than two-thirds of his teeth. The previous dental office spent a total of five minutes to address his needs. I offered to see if I could possibly help her son without hurting him. With his mother close by and supporting his head and neck, and using a special bite-block, through ear-piercing screams, we were able to successfully clean the hardened plaque from his teeth. We put this young patient on a three-month recall and allowed one hour for his dental visits. Three years later, he no longer cries when his teeth are cleaned. Through patience and perseverance, he has learned that we are his friends. He has a beautiful smile today and, along with touching our hearts, he is a constant reminder that everyone deserves adequate dental treatment.

We are truly a matrix of professionals who have been given the opportunity to render a valuable service to others.

Editor's Note: In an effort to combine her love of dentistry, writing poetry, and illustrating, Pasienza was inspired to write "'P' is for Patience." It is her hope that after reading the book, young children will develop a greater understanding of the importance of developing good dental habits. Pasienza's book is available by calling (800) 788-7654 or by visiting www. dorrancepublishing.com. Proceeds from book sales benefit the St. Louis Center in Chelsea, Mich., a caring, residential, family living and learning environment providing for the physical, emotional, and spiritual needs of children and adults with developmental disabilities.

By Joanne M. Pasienza, RDH