Treating medicated patients with heart disease

By Ann Eshenaur Spolarich, RDH, PhD

Dental professionals are already keenly aware of the widespread prevalence of cardiovascular disease, and observe many of their patients dealing with the related consequences of living with chronic cardiac conditions and related health challenges. Consistently, medications used to treat cardiovascular diseases are among the most commonly prescribed drugs in the United States.(1) It is important to remember that many classes of cardiac drugs have multiple indications, so clinicians should question their patients as to why the drug is being used and note any observations that they or their patients have made about side effects and/or efficacy. Pharmacists, physicians, and/or a drug reference guide may need to be consulted to verify each patient's drug indications and optimal treatment regimens. Compliance with taking cardiac medications and medical follow-up is often less than ideal due to intolerance of side effects, dosing schedules, cost and the need for frequent monitoring. For example, dental hygienists should never assume that a patient's blood pressure is being adequately controlled just because the patient reports having a prescription for an antihypertensive medication: vital signs taken at each visit and a historical record of blood pressure readings documented across time should be used to assess the clinical status of each patient. Many factors can alter a patient's blood pressure, including time of day, level of stress, compliance with medication regimens, and drug interactions.

Dental professionals are already keenly aware of the widespread prevalence of cardiovascular disease, and observe many of their patients dealing with the related consequences of living with chronic cardiac conditions and related health challenges. Consistently, medications used to treat cardiovascular diseases are among the most commonly prescribed drugs in the United States.(1) It is important to remember that many classes of cardiac drugs have multiple indications, so clinicians should question their patients as to why the drug is being used and note any observations that they or their patients have made about side effects and/or efficacy. Pharmacists, physicians, and/or a drug reference guide may need to be consulted to verify each patient's drug indications and optimal treatment regimens. Compliance with taking cardiac medications and medical follow-up is often less than ideal due to intolerance of side effects, dosing schedules, cost and the need for frequent monitoring. For example, dental hygienists should never assume that a patient's blood pressure is being adequately controlled just because the patient reports having a prescription for an antihypertensive medication: vital signs taken at each visit and a historical record of blood pressure readings documented across time should be used to assess the clinical status of each patient. Many factors can alter a patient's blood pressure, including time of day, level of stress, compliance with medication regimens, and drug interactions.

Sometimes, a patient unknowingly alters his blood pressure control from a drug interaction with an over-the-counter medication that goes unreported in the health history review. For example, chronic use of NSAIDS (e.g. taking for longer than 3 weeks) can reduce the efficacy of some antihypertensive medications, including beta blockers.(2)Many antihypertensive medications cause xerostomia, a chronic problem given that patients often take these medications for life. Oral sequelae of chronic xerostomia include functional difficulties, bacterial, fungal and viral infections, trauma and oral ulceration, and digestive problems. Dental hygienists should assess their xerostomic patients for both clinical signs and reported symptoms, and recommend appropriate therapies to provide symptomatic relief as well as to reduce and prevent oral disease risks.(3) Recommendations may include the use of power toothbrushes, oral irrigators, fluorides, xylitol, remineralization therapies and chemotherapeutic dentifrices and mouthrinses. Sonic brushing (Sonicare) has been shown to stimulate salivary flow in xerostomic patients and improve fluoride uptake in Streptococcus mutans biofilm.(4,5) Most antihypertensive medications cause orthostatic hypotension, so caution should be used when repositioning the patient to an upright position after dental treatment. Allow the patient to sit upright for several minutes prior to standing to reduce the risk of falls.(2)

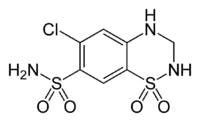

Other oral complications may be observed with cardiac medications. Thiazide diuretics (hydrochlorothiazide) are associated with causing lichenoid drug reaction, a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the drug that appears clinically similar to lichen planus. Warfarin (Coumadin) is associated with aphthous ulcerations, in addition to gingival bleeding. A chronic dry cough is often observed with patients taking ACE inhibitors, such as lisinopril. A rare, but notable side effect of ACE inhibitors is risk for angioedema of the face and oral cavity, which is why patients are encouraged to take the first dose while in the medical office.(2)Increased salivation and a sensitive gag reflex are associated with digoxin, the drug of choice used to treat congestive heart failure as well as for atrial arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation and paroxysmal atrial tachycardia. These oral side effects may pose difficulties with taking dental impressions.(2) Some calcium channel blockers, including nifedipine, verapamil, diltiazem, and amlodipine, are well-documented with causing gingival hyperplasia.(6)

Good oral hygiene is difficult to attain with hyperplastic tissue, so power brushes, power flossers, and power irrigators may all be helpful adjuncts to improve mechanical biofilm removal. Calcium channel blockers are indicated for the treatment of hypertension, angina and certain arrhythmias.(2)Finally, all dental professionals must be aware that epinephrine found in dental local anesthetics can cause unwanted adverse events in patients with cardiac disease. These effects include elevation in blood pressure, increased heart rate, and potential arrhythmias. Consult a drug reference guide and the patient’s cardiologist to ensure safety prior to administration. Maximum safe dosage for epinephrine in at risk patients is 0.04 mg, or the equivalent dose of 2 cartridges of epinephrine 1:100,000.(7)To stay current with new drug approvals and to find reliable drug information, all dental professionals should have access to a dental drug reference resource, preferably one that has an online database that can be accessed in real time. Oral adverse effects are typically found under side effect listings for the gastrointestinal tract, but may also be highlighted in a “special considerations” section for notable effects that impact dental treatment. Helpful resources that are designed specifically for dental professionals can be found by accessing the following websites: www.lexi.com/individuals/dentistry/ and www.us.elsevierhealth.com/Health-Professions/Pharmacy/book/9780323063623/Mosbys-Drug-Reference-for-Health-Professions/.

References

1. Top 200 Medications for 2009. Source: SDI/Verispan, VONA, www.drugtopics.com.2. Wynn RL, Meiller TF, Crossley HL. Drug Information Handbook in Dentistry. 17th ed. Hudson, Lexi-Comp Inc., 2011.3. Spolarich AE. Xerostomia and oral disease. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene, November 2011;9(11; Special Supplement):43-54.4. Papas A, Singh M, Harrington D, Rodríguez S, Ortblad K, de Jager M, Nunn M. Stimulation of salivary flow with a powered toothbrush in a xerostomic population. Spec Care Dentist. 2006;26:241-6.5. Stoodley P, Nguyen D, Longwell M, Nistico L, von Ohle Ch, Milanovich N, de Jager M. Effect of the Sonicare FlexCare power toothbrush on fluoride delivery through Streptococcus mutans biofilms. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2007;28:15-22.6. Wynn RL. An update on calcium channel blocker-induced gingival hyperplasia. Gen Dent, 1995;43(3):218-222.7. Malamed SF. Handbook of Local Anesthesia. 5th ed. St. Louis, Elsevier Mosby, 2004.

1. Top 200 Medications for 2009. Source: SDI/Verispan, VONA, www.drugtopics.com.2. Wynn RL, Meiller TF, Crossley HL. Drug Information Handbook in Dentistry. 17th ed. Hudson, Lexi-Comp Inc., 2011.3. Spolarich AE. Xerostomia and oral disease. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene, November 2011;9(11; Special Supplement):43-54.4. Papas A, Singh M, Harrington D, Rodríguez S, Ortblad K, de Jager M, Nunn M. Stimulation of salivary flow with a powered toothbrush in a xerostomic population. Spec Care Dentist. 2006;26:241-6.5. Stoodley P, Nguyen D, Longwell M, Nistico L, von Ohle Ch, Milanovich N, de Jager M. Effect of the Sonicare FlexCare power toothbrush on fluoride delivery through Streptococcus mutans biofilms. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2007;28:15-22.6. Wynn RL. An update on calcium channel blocker-induced gingival hyperplasia. Gen Dent, 1995;43(3):218-222.7. Malamed SF. Handbook of Local Anesthesia. 5th ed. St. Louis, Elsevier Mosby, 2004.

Ann Eshenaur Spolarich, RDH, PhD, is Clinical Associate Professor and Associate Director of the National Center for Dental Hygiene Research & Practice at the Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry at the University of Southern California.To read a previous article in RDH eVillage FOCUS written by Ann Eshenaur Spolarich, go to article.