Utility futility: A practical study on utility glove use and storage

Nitrile utility gloves are recommended for wear in the dental operatory when processing instruments. Deemed “heavy duty” and “puncture resistant” to provide more protection to the hands than thinner, patient-care gloves, nitrile utility gloves are recommended by both the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA).1,2 OSHA also recommends that each person in the office needing these gloves should have his or her own pair or pairs.2

Whether in the dental office or in a dental hygiene teaching setting, compliance is often poor for a number of reasons. The gloves can be oversized and tend to hamper fine-motor dexterity when disinfecting treatment areas or bagging instruments for ultrasonic or autoclave processing. Many offices offer a single pair of “communal” utility gloves for use by the entire staff. Nitrile utility glove manufacturers such as Hu-Friedy recommend that their product is “steam autoclavable up to five times.”3 However, malodor notably increases in the lining of the gloves with each subsequent autoclaving. Gloves are often stored improperly, causing retention of moisture and bacteria in the lining of the gloves.

The Owens State Community College (OCC) dental hygiene and dental assisting students had historically been offered communal nitrile utility gloves for operatory disinfection and instrument handling prior to processing, which were replaced with new communal gloves at the beginning of each semester. During the fall 2018 semester, students reported increasing malodor from the lining of the gloves as the semester progressed, which seemed to only worsen when the gloves were autoclaved. Additionally, some students were reporting dermatitis of the hands, which they suspected was caused by communal utility glove use. The American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology defines contact dermatitis as “symptoms such as a red rash, bumps or a burn-like rash on the skin.”4 When researching proper care and storage of utility gloves to prevent odor and bacterial growth, little to no information was available.

Upon assessment, new protocols were immediately put into place to (1) determine if individual/personal utility glove use versus communal utility glove use would decrease the incidence of dermatitis of the hands, and (2) to determine if improved washing and storage protocols would reduce malodor noticed with extended (one semester) use. Gloves were also swabbed and cultured for bacterial growth to determine what the best practices might be for reducing odor as well as bacterial counts.

Old protocol/communal use assessment

The nitrile utility gloves used communally were rated for odor by students at the end of the fall 2018 semester. Any incidents of contact dermatitis were also reported. The odor ratings were completed in a “blind” manner; the students rated odor on five different gloves:

- communal, turned inside out and washed with antimicrobial soap and air-dried

- communal, not washed/not autoclaved

- autoclaved right side out

- new (never worn/used)

- autoclaved inside-out

Gloves were rated on a scale of: no odor, slight odor, odor, malodor, malodor highly offensive. The findings, although inconsistent, rated the “new” glove with the lowest odor-offensive rating: 59% no odor and 32% slight odor. The gloves that had the highest odor-offensive rating were the glove autoclaved right-side out, with 18% slight odor and 18% odor; as well as the glove autoclaved inside out, with 18% odor, 14% malodor and 5% highly offensive malodor, suggesting that autoclaving did, in fact, increase malodor. Eight of the 22 students (36%) who completed the survey reported some incidence of dermatitis of the hands during the fall 2018 semester. Two of the 22 students (9.09%) had previously experienced dermatitis of the hands prior to entering the dental hygiene program.

Gloves were then swabbed and cultured for bacterial presence, using tryptic soy agar plates inoculated by sterile swabbing, utilizing the facilities at the Owens State Community College Life and Natural Sciences Department. On February 19, 2019, the five gloves provided were tested for bacterial growth. The inside (white) palm area of each glove was swabbed. The gloves were indicated by the following numbered order:

- Autoclaved right side out

- Turned inside out, washed with antimicrobial soap and autoclaved inside-out

- New (never worn or used)

- Turned inside out, washed with antimicrobial soap and air dried

- Communal, not washed or autoclaved

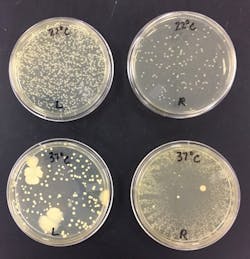

Ten plates were inoculated; five plates at 22°C (room temperature) and five plates 37°C (human body temperature; figure 1). On February 22, 2019; all plates were examined.

- Plate 1 (37°C) showed a single bacterial colony. This appeared to be transient growth, probably resulting from external contamination of the medium and not likely from the glove.

- Plates 1–4 (22°C) showed no growth

- Plates 2–4 (37°C) showed no growth.

- Plate 5 (22°C) and plate 5 (37°C) showed substantial growth. The 37°C plate showed approximately two times as many colonies growing as on the 22°C plate.

Per Robert J. Klein, OCC Life and Natural Sciences Department Laboratory Coordinator: “The growth appears to be Staphylococcus epidermidis. This is a normal flora of human skin. It is common and expected on any surface touched by human skin. This would correspond to the result of greater growth shown with incubation at human body temperature.” (personal communication, February 25, 2019)

This culturing suggested that washing the lining of the utility gloves (turning inside out) with antimicrobial soap and air-drying was as effective as autoclaving for reducing bacterial colonies, as plates 1, 2, 3, and 4 showed no growth. This method of disinfection effectively addressed both concerns of reducing risk for developing contact dermatitis from bacteria inside of the gloves and also reducing or eliminating odor caused by bacteria and retained moisture.

New protocol/individual use assessment

New nitrile utility gloves were distributed at the beginning of the Spring 2019 semester and used individually (personally). Each student labeled their personal pair of gloves with a permanent marker. Once a week, the gloves were turned inside out, washed with antimicrobial soap, and hung overnight by clipping by the fingertips with a binder clip to air dry (figure 2). Gloves were also stored, when not in use, by clipping by the fingertips with binder clips and hanging in designated storage areas. Faculty and students had considered that clipping/storing by the cuff or folding at the cuff and clipping for storage would trap moisture inside of the glove and impede drying or facilitate additional bacterial growth and malodor (figure 3).

Tryptic soy agar plates were inoculated by sterile swabbing to inside palm area of right (R) glove and left glove (L) of one pair of personal-use student gloves on May 15, 2019. The gloves had not been washed or air dried prior to culturing; of interest for this project was to compare bacterial counts in an individually worn glove to counts in a communally worn glove. As expected, all plates identified moderate to heavy growth of likely normal skin flora and light, indeterminate, intermittent transient bacteria. Again, this would correspond to the normal flora of human skin (figure 4).

Bacterial counts on the spring 2019 gloves were higher than counts on the fall 2018 gloves. This author speculates that the time lapse between the last time of use at the end of the fall 2018 semester (last week of November or first week of December) and the point at which the project was approved and the gloves were cultured (February 22, 2019) allowed for less numbers of viable bacteria to survive inside of the nonautoclaved, nonwashed communal glove. “The length of time bacteria are off a growth medium (i.e. natural skin surface or laboratory medium) is a factor in viability and observed growth. If the time from skin-glove contact to laboratory culture medium was shorter in the spring glove condition than in the fall glove condition, this may be a factor to account for greater growth evidence on the spring plate.” (R.J. Klein, personal communication, October 14, 2019) Mr. Klein also added that in his opinion, “skin-glove contact to plate inoculation time would have to be controlled in order to propose this as a primary consequence in results.”

Conclusion

Nitrile utility glove use for treatment area disinfection and handling and processing of instruments remains the recommended protocol for prevention of disease transmission and sharps injury. Gloves should be replaced when torn, punctured, or showing signs of wear. By implementing the following protocols, skin irritation, and malodor can be significantly reduced:

- Each person in the office needing nitrile utility gloves should have his or her own pair or pairs of gloves.

- On a weekly basis, turn the gloves inside-out and wash with antimicrobial soap, then allow the gloves to air-dry.

- Utilize a storage protocol that hangs gloves by the fingertips when not in use which will improve drying potential of the lining of the gloves, thereby reducing odor and possibly occurrences of dermatitis of the hands.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings—2003. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR-17):1-61. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5217.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2019.

2. FAQ - Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) – 2015. The Organization for Safety, Asepsis and Prevention website. https://www.osap.org/page/FAQPPE20154/FAQ---Personal-Protective-Equipment---2015.htm?page=SegmentEducators. Accessed October 5, 2019.

3. Lilac utility gloves. https://www.hu-friedy.com/infection-prevention/cleaning-care-products/utility-gloves/lilac-utility-gloves. Hu-Friedy website. Accessed October 6, 2019.

4. Contact dermatitis overview. American Academy of Allergy Asthma & Immunology website. https://www.aaaai.org/conditions-and-treatments/library/allergy-library/contact-dermatitis. Accessed October 5, 2019.

Susan Nichols, BIS, RDH, is an alumna of Owens State Community College in Toledo, Ohio, and a 31-year veteran adjunct faculty whose responsibilities include dental hygiene department coordinator, periodontology II instructor, and clinical faculty. As a proud member of the American Dental Hygienists’ Association, she has served as secretary, president elect, president and treasurer of the Toledo Dental Hygienists’ Association. Recent interests include grant writing and interprofessional education.