Dental anxiety: What role do sleep disorders play in dental fears?

By Jasmine Friend and Christian Hope Edmiston

Abstract

This paper is a comprehensive literary review of the correlation between sleep disturbances, dental anxiety, the oral manifestations, and how the dental professional can make a difference. The purpose is to increase the understanding that there is a strong correlation to the dental team between those who suffer from dental anxiety and their quality of sleep. There is an obligation on the clinician’s part to have a general idea on how these two conditions interplay as well as how to better assess and gather evidence of possible disturbances.

With this information, the dental team can make personalized behavioral change recommendations to the patient to alleviate specific issues. Survey results and in-depth research show profound evidence on how dental anxiety and sleep disorders directly affect one another.

In a study conducted by Almoznino and associates (2015), up to 50% of those who reported having dental anxiety also stated they do not get adequate sleep. Forty-five percent of survey responders also claimed to have used sleep aids in the past. But because 87% of survey responders reported to trusting the dentist, it is important to show how influential a dental team can be on their patients. It is the goal of this research paper to bring attention to this subject and instruct the whole dental staff on how to further assess for possible clinical manifestations of dental anxiety and sleep disturbances.

Sleep disorders can be described as the disruption of the quality and/or quantity of sleep due to certain disturbances and habits. The degree and depth of sleep disorders can hinder every aspect of a person’s life. Sleep plays a vital role in daytime functionality, as well as long-term effects on overall health (Chokroverty, 2008). With research and data collection, it is understood that sleep disorders have a strong correlation with dental anxiety. Those who suffer from dental anxiety have a greater risk of having a sleep disorder.

Dental professionals play an important role when it comes to dental anxiety management and sleep disorder assessment. As these professionals see patients on a regular basis, they have an upper hand in being able to detect possible sleep disorders that may be exacerbated by dental anxiety.

In addition to patient management, there is an obligation to have an understanding of how sleep disturbances may manifest orally as well as clinically. When working with a patient who may or may not admit they have dental anxiety, clinicians must always act in a way to make the patient feel safe and comfortable which will increase patient trust. With this underlying trust, the dental team can work with patients to assess for anxiety and possible sleep disturbances during the appointment. This allows the patient and dental team to work together to create goals and increase the overall health of the patient in a state of comfort.

Literary Review

Overview of sleep disorders

Sleep disorders manifest in various ways and are found to affect an immense amount of individuals. The American Sleep Disorders Association collaborated with the European Sleep Research Society, Latin American Sleep Society, and the Japanese Society of Sleep Research to create the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD) (Kryger, Roth, Dement, 2011). This manual provides an internationally accepted standard that allows for clinicians to better diagnose, study, and communicate information regarding sleep disorders.

Although the ICSD lists over 85 different specific sleep disorders, they are categorized into eight major sections: insomnia, breathing disorders, hypersomnolence, circadian rhythm, parasomnias, movement disorders, isolated symptoms, and other (The International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual, 2005).

For the purpose of this research paper, sleep disorders will be divided into two simple influencing groups: physically based sleep disorders and psychologically based sleep disorders. Physically based sleep disorders are induced by physical stimuli such as obstructed airways, bruxism, and restless legs syndrome tendencies. Psychologically based sleep disorders include those induced by anxiety, stress, post traumatic stress disorder, and behavioral changes (Chokroverty, 2008).

An overall understanding of the importance of sleep is critical in the field of public health providers. As “humans spend nearly a fourth to a third of their lives sleeping,” the time that is spent asleep is an important influence in determining the quality of life spent awake (Attanasio & Bailey, 2010). Quality sleep has shown to have major benefits in affecting healing, memory, learning, mood, and overall daily function (Attanasio & Bailey, 2010).

As health-care professionals assess the needs of their patients, simple investigative questions can reveal a new, unpaved pathway into the discovery of potential sleep disorder tendencies and risk factors. Since sleep has proven to be a vital factor in a patient’s quality of life, an argument can be made that inquiring about sleep quality can be just as beneficial and important as a cursory cancer screening. With such dramatic benefits from sleeping, it is unquestionable as to why health care professionals should consider sleep, or the lack there of, for the widespread benefit of their patients (Attansaio, Bailey, 2010).

Dental Implications

Because many people visit their dental office more often than they see their primary physician, dental professionals have an obligation to take into consideration the overall health of the patient rather than just possible oral conditions (Attanasio & Bailey, 2010). Due to this practice, dental professionals play a major role in evaluating the patient for other conditions outside of the mouth. In some cases, certain diseases manifest early signs in or near the oral cavity, which give dental clinicians an opportunity to catch these diseases early for the benefit of the patient (Attanasio & Bailey, 2010).

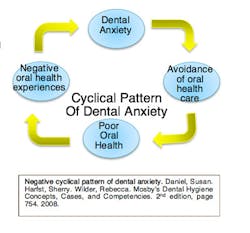

Dental anxiety can be described as an irrational fear of dental related objects and procedures that manifests as a strong emotional response (Almoznino et al., 2015). Wilkins (2013) also described it as a negative response to an upcoming event where there is an uncertain outcome. This is also a learned reaction due to past personal experiences and stories told from others.

In situations where patients suffer from varying degrees of dental anxiety, sleep quality is an avenue dental professionals may consider exploring more. Almoznino and associates (2015) conducted a research study that compared those with dental anxiety, a hyperactive gag reflex, and a control group to their sleep quality. They found that around 50% of the dental anxiety group and 40% of the gag reflex group were poorer sleepers compared to those who did not manifest with these conditions. A result and conclusion of 50% was a significant finding because it showed that there was a strong correlation between sleep quality and dental anxiety. Limitations are found in this research study due to the fact that it is not noted how long this decreased sleep quality is manifested.

Special consideration must be made if times of inferior sleep are generalized throughout life or just in acute moments before or after an upcoming dental exam. A suggested recommendation for further study is to conduct more in-depth research on the sleep aspect. Since there was such a high percentage of those with dental anxiety who reported poor sleep quality, further investigation can be done to evaluate the extent of the sleep deprivation. Some questions should be answered, including: 1. “How long did the poor sleep last?” 2. “Did you have a history of sleep disorders before the study?” 3. “What was the extent of your sleep deprivation?”

In contrast, Cohen, Fiske, and Newton (2000) conducted a study on the influence of dental anxiety on a person’s daily life. They found that dental anxiety had an impact on several aspects of life, including: cognitive, physiological, social, behavioral, and health. Interestingly enough, the major factor under the health implications were sleep disturbances. Their research showed that patients commonly reported an inability to sleep, and disturbed sleep due to nightmares prior to a dental appointment and “at times remote from a dental appointment” (Cohen, Fiske, & Newton, 2000). This shows that dental anxiety primarily and powerfully causes disruptions in someone’s sleeping habits.

This is another supporting study that backs up the importance of why dental professionals need to be aware of how sleep is a major factor in dental and total health.

As noted in the previous study, there were limitations with each research project. In this case, the published results were gathered only through extensive interviewing. No clinical investigations were done to find particular levels or extent of sleep disturbances. Reports were solely based off what the patient claimed in the interviews. Suggested recommendations would be to study further the sleep disturbances each patient reported and to gather clinical assessments on whether clinical findings match what patients claim to manifest. Perhaps measurable and attainable results from a polysomnography test would be able to confirm these claims (Cohen, Fiske, and Newton, 2000).

With millions of people in America suffering from sleep disorders, not including those that go undiagnosed or untreated, it is difficult to determine which patient is suffering from a sleeping disorder or who is at risk for it (Chokroverty, 2008). Since sleep disorders have been a continued and long-standing subject of study, certain factors have been seen to contribute to greater prevalence of sleeping conditions. These can include: “aging; female gender; lower socioeconomic status; being divorced, widowed, or separated; depression; stress; drug or alcohol abuse; and certain medical disorders” (Chokroverty, 2008).

With this list in mind, dental workers can be more aware of those who are at higher risk for having a sleep disorder. Careful attention must be maintained as busy health-care workers go about their routines that each file, chart, and patient are unique. Each situation is different, and an idea of a “template care plan” does not apply to all patients.

This is important when considering how each patient’s personal situation can cause them to manifest with different issues, including sleep disturbances. As dental professionals ideally see patients at least every six months, special consideration can be taken to open communication with each patient about their lifestyle and certain changes in their lives. As patients are dynamic and continually living, dental workers must continually inquire on updating the status of a patient’s stress level, socioeconomic status, and medical changes that affect sleeping patterns (Chokroverty, 2008).

As dental professionals continue to seek medical histories from their patients, a comprehensive drug list is commonly acquired. This is for clinicians to have a better idea of what conditions their patients are being medicated for, as well as know special dental considerations regarding those medications. Common drugs used for sleep aids are hypnotics, benzodiazepines, and non-benzodiazepines (Douglas, 2002).

In Clinicians’ Guide to Sleep Medicine, Douglas explains how long-term use of these agents can have the direct opposite effect on sleep and daytime performance. After taking these drugs over a long period of time, they no longer have a positive effect on sleep nor do they improve daytime function. These drugs also have a high prevalence of potential dependence, which may lead to patient addiction later.

It is important for dental professionals to know the potential effects sleep aids can have on their patients. If they suspect their patient has a sleep disorder, and/or they report taking a regular sleep aid, it would be ethical for the clinician to tell them of the potential negative effects that come from taking long-term sleeping drugs (Douglas, 2002).

The authors of this research paper created a survey that was given in hopes to gather more insight on dental anxiety and sleep disturbances. According to the survey taken for the purposes of this research paper, 45% of total participants reported to have taken a sleep aid in the past. Of those who indicated they had high anxiety, up to 50% claimed to have taken a sleep aid in the past.

A result of 45-50% is significant if dental professionals take into consideration the time and moment people take sleep aids. If a person has dental anxiety, and they have a dental appointment the next day, there is a high potential sleep aids may be consumed prior to that appointment. Expanding that situation, if a person deals with general anxiety (not just dental anxiety), there is also a high chance sleep aids are used for regular sleep maintenance and daily performance.

This shows that dental professionals may continually inquire if sleep medication are used and for what amount of time. When understanding the effects of long term sleep aids and the importance of quality sleep, clinicians have an obligation to counsel their patients if they suspect any sleep disturbances or even drug dependence.

Physically based sleep disorders and dental management

As stated above, physically based sleep disorders are induced by physical obstructions or manifestations that can cause someone to have impaired sleep. Some physically based sleep disorders are extremely uncomfortable and bothersome, such as restless legs syndrome or periodic limb movement. However, other physically based disorders may not be as exasperating such as with bruxism and an obstructed airway that causes snoring. With these conditions, dental professionals may be able to recognize certain oral manifestations and start a conversation with the patient regarding sleep quality (Attansaio & Bailey, 2010).

Bruxism can be defined as “an oral activity characterized by grinding or clenching of the teeth during sleep, usually associated with sleep arousals” (Attanasio & Bailey, 2010, pg. 56). If attrition, abfraction, hypersensitivity, restriction of mandibular movement or changes in the periodontal tissue (such as tori) are evident, bruxism may be a cause (Attanasio & Bailey, 2010). Knowing these signs and symptoms will help dental professionals identify those who may have sleep related bruxism, which, in turn, can lead to the discovery of a sleep disorder. This is important because the patient may report constant fatigue, but never think to consider it being related to bruxism. In this situation, knowledge is power. The patient can be referred to a doctor that can help alleviate the fatigue (Attansaio & Bailey, 2010).

Another physically based sleep disorder manifestation is an obstructed airway, resulting in snoring. If the muscles of the soft palate or the muscles around the upper airway hinder the involuntary action of breathing, snoring can arise as well as apnea or hypoventilation. Oral manifestations of snoring can be enlarged tonsils, obstructed view of the oropharynx from tongue placement, dry mouth, and height of the soft palate.

Scalloping of the tongue may also be evident as it can be caused from tongue thrusting due to inadequate space in the mouth for tongue movement, especially during sleep. Again, these signs are important to note when doing intraoral examinations as they may be attributed to sleep disturbances. It is important for the clinician to remember that while performing cancer screenings, noting benign manifestations can be just as important, because they may lead to the detection of sleep disorders (Attanasio & Bailey, 2010).

Psychological based sleep disorders

The second category of sleeping disorders to further understand would fall under psychologically based sleeping disorders. These psychological disturbances root mainly from anxiety. Each person’s anxiety varies and will change with different experiences. Everyone has their own degree of nervousness, fear, tension, and worries. These can all build up and cause issues with quality and quantity of sleep (Cleveland Clinic, 2010).

Sleep disorders are found in over half the patients that have generalized anxiety disorders. Usually these patients have a more difficult time falling asleep due to being unable to relax or to stop worrying. If insomnia occurs, the anxiety levels and stress can raise even more. Some people struggle with staying asleep during the night, through sleepwalking, sleep talking, nightmares/night terrors, and REM behavior disorder (National Sleep Foundation, 2015).

Sleep hygiene and clinician responsibility

“Sleep hygiene is defined as a set of behavioral and environmental recommendations intended to promote healthy sleep” (Irish et al., 2015). As dental professionals give oral hygiene instructions, additional sleep hygiene instructions may be indicated for those with sleep disorders. Just as stress reduction protocol is important for oral and overall health, sleep hygiene recommendations follow that same idea. Irish and associates (2015) conducted a literary analysis and evaluation on the role of sleep hygiene in an overall view of public health. They gathered information on popular sleep hygiene recommendations such as regular exercise, managing stress, reduce bedroom noise, scheduled sleep time, and avoidance of caffeine and alcohol. Neil Douglas (2002) also noted in his text the avoidance of certain activities in bed (such as studying), the banishment of clocks, and the reduction of worrying when sleep does not come.

Recommendations such as these may be vital when giving suggested home and self-care modifications to their patients. It is important to stress the intent to improve overall health, not just oral health. When clinicians allow for communication and conversation with their patients, they will begin to understand that dentists and hygienists are not only trained to care for the mouth, but for the entire body. With this comes increased trust and stronger patient-practitioner relationship.

In the article from Irish and associates (2015), it is also mentioned that when two to four personalized sleep hygiene suggestions were made, follow-up reports showed that increased sleep benefits were retained for over a year. This is significant because it shows that taking just two minutes to inquire about a sleep disorder and recommending a personalized sleep hygiene modification can make a vast difference in a patients’ life.

From the dental anxiety and sleep disturbance survey that was mentioned above, 87% of total responders reported to trusting the dental team. Again, 87% is an astonishing percentage because that shows the majority of people trust the judgment and suggestions of their dental team. This gives dental professionals a huge benefit and responsibility to continue to uphold trust and not abuse it. It shows the potential influence a dentist or hygienist can have on a patient when it comes to making recommendations as well as patient treatment. With trust, a simple suggestion to seek help or to change a behavior can positively be life altering for the patient. It shows how important and significant this career can be (Irish et. al., 2015).

Correlation of dental anxiety to specific phobias

Through research it has been found that those that struggle with inadequate sleep, struggle with general anxiety. Most people with general anxiety also manifest with dental anxiety. This portion of the research paper correlates the relationship between sleep disturbances and those with dental anxiety. Research was done to further investigate what specific aspects of dentistry cause individuals to have anxiety, thus causing possible sleep loss. In order to further understand this dilemma, the top phobias were researched and several correlated with a dental experience (Wilkins, 2013).

Manifestations of dental anxiety

Approximately 20% of adults in the United States have reported to make delays in visiting the dentist due to their dental anxiety. These individuals habitually experience dental anxiety often has one of more of the following towards dentistry: negative connotations, outlooks, and reservations; fright response; sleep disorders; or an impaired functioning in work and social life. Dental anxiety can be directly or indirectly related to dentistry. Direct experiences can be from dental pain; behavior of dental staff member(s); dental treatment causing emotional distress (loss of control); and distressing stories told by others (Humphris & King, 2011).

Negative dental stories have even been put into the social media, particularly on the video sharing website known as YouTube. There was a study done by the Journal of Medical Internet Research in which they had a panel of three investigators look at 27 videos involving 32 children and adolescents’ opinions of their dental experiences (Gao, Hamzah, Yiu, McGrath, King, 2013). The negative social media can increase the amount of younger patients that struggle with dental anxiety.

Dental anxiety can be caused indirectly by distressing experiences that are not related to the dental setting. These can include one or more of the following: sexual abuse; war trauma; severe traffic accidents; distressing medical experiences; and physical assault. It is estimated that one out of every six American women have been the victim of an attempted or completed rape in her lifetime, meaning approximately 17.7 million American women are living with this victimization.

For men, it is estimated that 1 in 33 has experienced an attempted or completed rape and from 1995 to 2010, 9% of rape and sexual assault victims were male and 91% were female. Approximately 5% of children under 12 have experienced either sexual assault or rape in the United States (RAINN, 2015). These are just the statistics for sexual abuse in the United States; these numbers do not even include those who have experienced war trauma, severe accidents, medical experiences, and other assault. Any patient can have a direct or an indirect reason for dental anxiety. Clinicians could pay more attention to the patient’s behavior and body language throughout the appointment to understand their triggers and issues (Roan & Singhvi, 2013).

Five dental related phobias

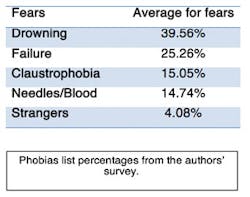

Everyone has a fear of something. Some people take that fear and let it affect their lives, where they go, and what they do. Fear of the dentist is a term that is commonly used. However, there are aspects that have to make up that fear. After taking a look at the most common phobias and fears, research was done on five of the top 25 phobias and how they directly relate to dentistry.

Trypanophobia, the fear of needles, affects as much as 10% of the world’s population (Fear Of, 2015). The fear may not even be physical, but instead psychological because they fear it will hurt. Needles are associated with doctors and dental visits, thus creating a fearful stimulus of this type of experience. It is stated that the fear of needles can be explained by the fact that injections are usually unpleasant/painful for most people. Needles can also cause disease, and could remind the patient of bad experiences (Antony & Watling, 2006). There is also the fact that society creates these negative statements that are made about needles such as: “Be brave for your shot” or “It will only hurt for a few seconds.” For children, fear of needles is almost expected. However, in adults it is expected for the patient to understand it is a necessity for some treatments. Some ways to tell if the patient is struggling with this fear/phobia are facial expressions of fear, an increased blood pressure, having short breath, and tremors. Those with more extreme fears could lead to panic attacks or fainting (Antony & Watling, 2006). There is a level of fear that does not affect treatment or the patients’ health. However, there is also a level of fear that once surpassed will prevent the patient from having necessary treatment, vaccines, and lead to a worsening of the medical issue that can cause more pain then the needle would have caused. There are several treatments available for this fear. One, by gradual exposure to the needle, cognitive behavioral therapy, slowed breathing, relaxing, medication (such as nitrous) and discussing their fear openly (Antony & Watling, 2006). Simply taking the time to discuss the issue with patients could make all the difference, and perhaps all they needed was to discuss their issue with someone that cared.

The next fear is known as aquaphobia, also known as the fear of water/ drowning. These patients could be afraid because they imagine themselves having to gasp for a breath, feel as though they are choking, drowning, or they may imagine water ultimately leading to their own death. Approximately, 19.2 million people in the United States struggle with this fear in some form (Fear Of, 2015). These patients will most likely have an issue with the ultrasonic, the handpiece, and the air water syringe. The reasons that explain this fear are: personal experience or witnessing a traumatic event, learned from the environment, and for some who are not exposed to very much water.

Overall, patients that have higher anxiety are much more likely to develop this fear. Some things that clinicians can look for are patients who display the following: avoidance of water, may claim a “bad gag reflex,” show anxiety when exposed to water, irregular coughing, have poor hygiene in general, a change in heart rate or breathing due to water exposure, they feel faint, or show a loss of control through perspiring, crying, and quivering (Bailey, 2009).

For patients who are afraid of the amount of water that is used in the dental office, it is important that clinicians do their best to keep them relaxed. Some ways to help these patients are to allow them to hold the suction, give them more breaks, turn down water settings, explain procedures, and allow them to use nitrous for anxiety. It is also important that clinicians refer the patient to a specialist if they are in need of psychological therapy for the severity of their phobia. The main way to help fearful patients overcome this is repeated exposure gradually overtime in a healthy, trusting environment (Roan & Singhvi, 2013).

Claustrophobia is a well-known fear of tight or crowded spaces that nearly 4% of people struggle with across the world (Ost, 2004). The word “claustrophobia” is commonly used for individuals to express discomfort or irritation, and is often an overused statement. These individuals avoid elevators, airplanes, tunnels, crowds, and other tight places. Reasons that one might have claustrophobia are traumatic past experiences, spatial distortion, higher anxiety, and history of panic disorders. Physically, the patient may experience hyperventilation, accelerated heartbeat, perspiration, feeling faint, nausea, and shaking (Roan & Singhvi, 2013).

Psychological symptoms are thoughts of being trapped, paranoia of death, avoidance from certain situations, and being unable to distinguish between reality and fantasy. Ways that clinicians can help them are through emotional support, give them space when they need it, having referrals, slow exposure, and try to make the environment as open as possible such as pulling the light farther back or not sitting so close (Ost, 2004).

The next phobia faced in the dental office is known as anthropophobia. It is the fear of other people or society. Individuals that struggle with this phobia may even fear those who are close to them due to paranoia, and see them as strangers or threats, even though most of the time they are conscious that the thought is illogical (Beidel, Turner, 2007). How can these people be expected to come into the dental office and be under the care of a hygienist they do not know, or a new assistant, doctor, or front desk personnel? It is recommended that clinicians keep in mind that certain patients simply may not like new people. It is best to remain professional and not let it affect personal self-worth as clinicians.

Examples of anxiety symptoms that clinicians can look for are: avoiding socializing at all costs possible, feeling panic when meeting new people, fear of embarrassment, and thoughts of death (Beidel, Turner, 2007). Physical signs such as increased heart rate, shortness of breath, feeling like being choked, difficulty in swallowing, increased blood pressure, sweating, trembling, and crying. Those that struggle with this issue are in need of help.

Suggested ways to help are: allowing the patient to realize this can be overcome, cognitive behavior and behavior therapies, and repeating statements that help the patient feel calm and positive (Beidel, Turner, 2007). A unique way of dealing with this phobia is a Japanese therapy based on Buddhism called “Morita,” which involves the patient to accept the fear and create positive ways of thinking about it (Fear Of, 2015).

Finally, there is atychiphobia, which is known as the fear of failure (Fear Of, 2015). There is a healthy amount of worrying about failing and an unhealthy amount that affects ones’ life and decisions. Those that struggle with this phobia usually have unrealistic standards of behavior and expectations. This condition could possibly be caused by a lack of self-confidence, bad experiences, fear of risk taking, overly demanding childhood, as well as cultural and societal expectations. Physically seen signs can be: a lack of good sleep, tension headaches, muscle pain sweating, trembling, twitching, and even panic attacks. To help patients that struggle with this phobia, clinicians can: encourage, motivate, give positive feedback, and listen to their concerns. However, the most important thing the dental team can do is to give proper instructions, but to not make the patient feel like they are doing a poor job. This could discourage them even more (Kase, 2006).

Research survey results

Of the responders, 48% said they have low general anxiety, and 14% said they have high general anxiety. The two greatest fears were first the fear of drowning and the second was the fear of failure. For dentistry, 59% people had a negative response as to why they may be afraid of the dentist, while 41% did not report any negative connotations with the dentist. Thirteen percent said they do not trust the dentist, and 24% visit the dentist once a year or longer. For sleep, results showed 22% of people get three to six hours of sleep a night, 72% get six to eight hours of sleep a night, and 6% get more than eight hours of sleep at night. Lastly it was noted that 45% claim to have used a sleep aid. These overall findings provided a baseline for the majority of people who come into the dental office.

It was found that those who reported having high anxiety were 84% female, 43% work in health care, and 14% in government. The highest average fear for these subjects was the fear of failure at 41% and claustrophobia coming in second at 35%. For dentistry, 72% had a negative fear of going to the dentist, and 23% stated they do not trust the dental team. For sleep, 14% said they get three to six hours of sleep a night, and 50% use some type of sleeping aid. The answers were isolated for those who chose three to six hours of sleep. Of those people, 36% work in health care, 40% stated they have moderate to high anxiety, 59% had something negative to say about going to the dentist, 9% say that they don’t trust the dentist, 23% take longer than a year to visit the dentist, and surprisingly 64% don’t take sleep aids. This shows that those with reported higher general anxiety levels get less sleep and have more fear towards the dentist.

Finally, those who answered failure as their highest fear were analyzed. The authors were interested in the fact that failure, a non-painful experience would be more frightening then the others which could pose an actual threat. Results showed 42% were between the ages of 18 to 25, 33% in health care, 59% stated they have moderate to high anxiety, 54% had a negative connotation to dentist, 9% don’t trust dental team, 75% have regular recare visits from 3 months to a year, 66% get more than 6 hours of sleep, and 50% use sleep aids.

Unexpected dental phobias

Of the top 100 fears of 2015, approximately 19 of those phobias can be experienced by a patient at a regular recare visit. Dental professionals are more aware of certain anxieties that the patient might be experiencing, such as being afraid of radiation, choking, pain, germs, and certain sounds like the handpiece. There are other specific fears that the patients could be experiencing that are not as obvious. Here are a few examples: androphobia (fear of men), gynophobia (fear of women), iatrophobia (fear of doctors), mysophobia (fear of germs), sidonglobophobia (fear of cotton balls), telephonophobia (fear of talking on the phone), ligyrophobia (fear of loud noises), and photophobia (fear of light) (Fear Of, 2015). However, this is just a basic list of 100 phobias.

There is an unmeasurable amount of people who struggle with phobias and unmeasurable amount of specific phobias that can affect someone’s life and sleeping patterns. As clinicians, there is a need to be aware of the different struggles that the patient could be experiencing and know how to relax them when they are in distress.

It is clear to see that there is a wide variety of fears that any patient can experience. From needles and bleeding, to feeling judged by a stranger, the dental office can be a very negative experience for a person.

The facts are that clinicians cannot change past dental experiences. The pain cannot be taken away from experiences in childhood nor can their fear be taken away. However, a motivated dental team can change their minds about dentistry. It can show them how a dental staff should treat their patients. It can make them want to come back. It can make them feel safe and cared for. Patients must feel that clinicians care for their entire well-being, including their oral hygiene, sleep hygiene, and overall health. Most importantly a good clinician can earn and keep their trust.

Conclusion

With all this new information and deeper knowledge of sleep disorders and dental anxiety, dental workers should understand the importance of taking a few extra steps to inquire about sleeping habits. Reite, Ruddy, and Nagel (2002) suggest taking a simple sleep history with questions such as “Are you satisfied with your sleep?” “Are you excessively sleepy during the day?” and “What medications have been used to treat these symptoms?”

Perhaps clinicians can also minimize the patients discomfort while in the office by: allowing them to hold the suction, explain procedures, paying close attention to their needs, and most importantly making sure not to lecture the patient but to encourage them instead. With simple assessment questions and small changes such as these, an avenue for open communication can begin and hopefully lead to a plan to combat the disturbances.

Dental professionals should also take the time to note the oral manifestations that were mentioned above to gather more information on a sleep disorder the patient may not know they are at risk for. “For the sake of the patient, the dentist should have an ever- increasing awareness of medical issues relative to their patients” (Attanasio & Bailey, 2010, pg. 31). By having this awareness, patient-to-physician-to-dentist communication is amplified, which can directly increase the care and health of that patient. There is a chain reaction occurring: anxiety of failure leads to less sleep, which leads to less dental care, which leads to poor health, and circulates back to anxiety failure.

The entire dental team can influence the care of the patient by inquiring about their sleep health and their anxiety levels. The front desk, for example, could schedule the patients in the afternoon if they are suffering from a sleep disorder or can send text message alerts to the patient with telephone anxiety. Patient comfort and trust could be more important in the dental office. It is impossible to change a persons’ past, but their future can change.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Kandice Swarthout-Roan, MS, RDH, for her constant encouragement and support regarding this research paper. We would also like to thank Amber Allen BA, RPSGT, RST for her time and knowledge that she shared regarding sleep studies.

References

- 1. Almoznino G, Zini A, Sharav Y, Shahar A, Zlutzky H, Haviv Y, Aframian D. (2015). Sleep quality in patients with dental anxiety. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 61, 214-222.

- 2. Antony M, Watling M. (2006). Overcoming medical phobias: How to conquer fear of blood, needles, doctors & dentists. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

- 3. Attansaio R, Bailey D. (2010). Dental management of sleep disorders. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing.

- 4. Bailey E. (2009). Aquaphobia: the fear of water. In Health central. Retrieved from http://www.healthcentral.com/anxiety/c/22705/71074/aquaphobia-water/

- 5. Beidel D, Turner S. (2007). Shy children, phobic adults: Nature and treatment of social anxiety disorder (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

- 6. Chokroverty S. (2008). 100 questions & answers about sleep and sleep disorders (2nd ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett.

- 7. Cleveland Clinic. (2010, October 1). Sleep and Psychiatric Disorders. In Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved from http://my.clevelandclinic.org/services/neurological_institute/sleep-disorders-center/disorders-conditions/hic-sleep-and-psychiatric-disorders.

- 8. Cohen S, Fiske J, Newton J. (2000). The impact of dental anxiety on daily living. British Dental Journal, 189(7), 385-390.

- 9. Daniel S, Harfst S, Wilder R. (2008). Mosby’s dental hygiene concepts, cases, and competencies. (2nd ed.). St. Louis, MO. Elsevier Inc.

- 10. Douglas N. (2002). Clinicians' guide to sleep medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- 11. Gao X, Hamzah S, Yiu C, McGrath C, King N. (2013). Dental Fear and Anxiety in Children and Adolescents: Qualitative Study Using YouTube. In Journal of Medical Internet Research. Retrieved from http://www.jmir.org/2013/2/e29/.

- 12. Humphris G, King K. (2011). The prevalence of dental anxiety across previous distressing experiences. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25, 232-236.

- 13. Irish L, Kline C, Gunn H, Byesse D, Hall M. (2015). The role of sleep hygiene in promoting public health: A review of empirical evidence. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 22, 23-36.

- 14. Kase L. (2006). Anxious 9 to 5. Oakland, CA: Raincoast Books.

- 15. Kryger M, Roth T, Dement W. (2011). Principles and practice of sleep medicine (5th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier.

- 16. National Sleep Foundation. (n.d.). Depression and Sleep. In National Sleep Foundation. Retrieved from https://sleepfoundation.org/sleep-disorders-problems/depression-and-sleep.

- 17. Ost L. (2004). The claustrophobia scale: a psychometric evaluation. In Science Direct.

- 18. Phobia List-Ultimate List of Phobias and Fears (2015). In Fear Of. Retrieved from http://www.fearof.net/.

- 19. R.A.I.N.N. (2015). Who are the Victims. In Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network. Retrieved from https://rainn.org/get-information/statistics/sexual-assault-victims.

- 20. Reite M, Ruddy J, Nagel K. (2002). Concise guide to evaluation and management of sleep disorders (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- 21. Roan K, Singhvi, P. (2013). The roots of dental fears. RDH magazine.1-8.

The international classification of sleep disorders: Diagnostic and coding manual (2nd ed.). (2005). Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine. - 22. Wilkins E. (2013). Anxiety and pain control. In Clinical practice of the dental hygienist (11th ed., pp. 554-576). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.