Endodontic insight: Where should the gutta-percha point end for optimal endodontic success?

This article first appeared in the newsletter, DE's Breakthrough Clinical with Stacey Simmons, DDS. Subscribe here.

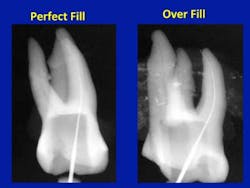

For many years, this was a difficult question to answer. Most schools and academic institutions taught that the gutta-percha point should end at the radiographic apex of the root. This is the zenith or highest point of the root as seen on the clinical x-ray. Yet when we did that, a certain percentage of patients felt uncomfortable and could not easily bite on their endodontically treated teeth. Those same teeth sometimes did not heal on x-ray or, worse, first developed a radiolucency after endodontic treatment. Since the endodontic literature did not address this problem in those years, we blamed it on a host of other variables during the course of treatment.

ADDITIONAL READING |Endodontic insight: Maximizing canal cleansing with minimal dentinal weakening

Since the advent of the electric apex locator and the subsequent research that has gone with it, we can now understand the nature of the problem, its cause, and a remedy for its solution. In order to comprehend what is going on, we first must understand three definitions:

- Radiographic apex—The highest point or tip of the root as seen on the x-ray.

- Anatomic apex—The point where the neurovascular bundle enters the root apex.

- Constriction—The narrowest point of the canal (usually located within 2 mm of the anatomic apex).

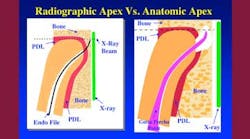

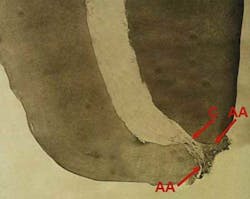

We had clues to the answer to the problem in the literature for many years, but no one connected the dots. The literature stated that the radiographic apex and the anatomic apex did not coincide in more than 50% of the canals. Recently, El Ayouti et al. showed that the anatomic apex was short of the radiographic apex in 88% of the canals,and in 5% of the canals the anatomic foramen was more than 2 mm short of the radiographic apex. (1) In this article, they stated that root fillings extending to the radiographic apex are actually over fillings in most of the canals. Here is the answer to that perplexing clinical problem. The x-ray looks perfect and the gutta-percha is right at the radiographic apex, so why does the tooth hurt? The answer is that in the clinical reality (figure 1), the anatomic apex does not coincide with the radiographic apex and, consequently, the instrumentation is long and the filling material (gutta-percha and sealer) are both past the anatomic apex.

In figure 1, we see that the file has been pushed through the anatomic apex to reach the radiographic apex. It goes through the periodontal ligament and bone to get there. The dentist now instruments to this incorrect measurement. The result is a lot of postoperative pain once the anesthesia wears off. Then, to make matters worse, the gutta-percha is now pushed through the anatomic apex and sealed into the ligament and bone. No wonder it sometimes does not heal and often causes the patient discomfort.

We now know that if we place the gutta-percha at the radiographic apex, we will be out of the tooth and in the PDL (periodontal ligament) and bone between 50% and 88% of the time. The literature comes to our rescue. Schaeffer et al. showed that a better success rate is achieved when obturation is short of the apex. (2) Then, many articles state that the root canal should be filled to within 2 mm of the radiographic apex for optimum success. (3-8)

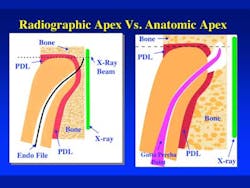

The next question to ask is why within 2 mm of the radiographic apex? The answer is that the anatomic apex is usually located between 0 and 2 mm from the radiographic apex. Therefore, the outer boundary of our gutta-percha should be the anatomic apex. This will prevent the filling material from going into the periradicular tissues. Figure 2 shows gutta-percha extending past the anatomic apex and short of the radiographic apex. On x-ray this obturation will appear short of the radiographic apex, yet the gutta-percha will be extending into the ligament and bone. Not a good situation.

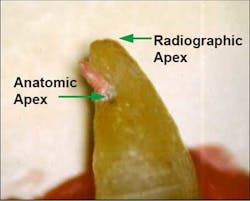

Figure 3 shows the x-ray of a molar with the measuring file in place. In one angle the measurement is perfect for the radiographic apex. In the reality view, we can see that the file is approximately 1-2 mm beyond the anatomic apex. Figure 4 is a photo of the same tooth, demonstrating that the anatomic apex is really 1-2 mm short of the radiographic apex.

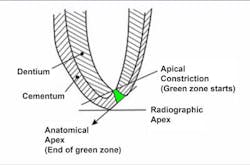

Now we know that for optimum success the outer boundary of the gutta-percha fill should be the anatomic apex. There is only one instrument that will locate that anatomic landmark, and that is the newer apex locators. The newer apex locators (within the last 10 years) are very accurate. Please read the instructions. Each machine is marked differently and records the constriction and anatomic apex at different locations on their readout scale. The constriction is the narrowest point in the canal (see figure 5) and is usually 0.5 mm to approximately 1 mm from the anatomic apex.

Therefore, summarizing and collating all this information, we come to the following conclusion: In order to obtain the highest endodontic success rate and least amount of postoperative complications, the obturation material should be placed anywhere between the constriction and the anatomic apex. The green area in figure 6 represents this.

Clinically, we as dentists must change our concept of endodontic beauty. The optimum endodontic obturation should no longer be gutta-percha to the radiographic apex, but rather a fill that looks 0 mm to 2 mm short of the radiographic apex for maximum success.

This article first appeared in the newsletter, DE's Breakthrough Clinical with Stacey Simmons, DDS. Subscribe here.

ADDITIONAL READING |Endodontic insight: Thorough root canal cleaning and shaping while preserving tooth structure

References

1. El Ayouti A, Hulber-J M, Judenhofer MS, Connert T, Mannheim JG, Dipl-Ing, Lost C, Pichler BJ, Von Ohle C. Apical vonstriction: Location and dimensions in molars-A micro-computed tomography study. J Endod. 2014;40:1095-1099.

2. Schaeffer MA, White RR, Walton RE. Determining the optimal obturation length: A meta-analysis of literature. J Endodon. 2005;31:271.

3. Kojima K, Inamoto K, Nagamatsuk K, Hara A, Nakata K, Morita I, Nakagaki H, Nakamura H. Success rate of endodontic treatment of teeth with vital and nonvital pulps. A meta-analysis. Oral Surg, Oral Med, Oral Path. 2004;97:95-99.

4. Ng YL, Mann V, Rahbaran S, Lewsey J, Gulabivala K. Outcome of primary root canal treatment: systematic review of the literature-Part 2. Influence of clinical factors. Inter Endod J. 2007;41:6-31.

5. Peak JD, Hayes SJ, Bryant ST, Dummer PM. The outcome of root canal treatment. A retrospective study within the armed forces (Royal Air Force). Br Dent J. 2001;190:140-144.

6. Chandra A. Discuss the factors that affect the outcome of endodontic treatment. Aust Endod J. 2009;35:98-107.

7. Gomes AC, Nejaim Y, Silva AIV, Haiter-Neto F, Cohenca N, Zaia AA, Silva EJNL. Influence of endodontic treatment and coronal restoration on status of periapical tissues: A cone-beam computed tomographic study. J Endod. 2015;41:1614-1618.

8. Ricucci D, Russo J, Rutbert M, Burleson J, Spangberg L. A prospective cohort study of endodontic treatments of 1,369 root canals: Results after 5 years. OOOE. 2011;112:825-842.