Eating disorders: A brief overview of the dentist’s role in diagnosis and management

It was a typical busy day—three hygiene exams, a crown patient in one chair, and two other patients needing a moment of my time. My dental assistants were directing me accordingly, and there was a good hum in the air with regard to practice flow.

But that all stopped when I did an exam on a patient whom I initially thought was a healthy 27-year-old woman with notable erosive lesions on the lingual aspect of her maxillary teeth. First thing I thought, “This isn’t normal at all.”

My patient

It was clear, due to the pattern of wear, that this patient had a history of bulimia but wasn’t aware of the oral manifestations that had resulted from her binge-and-purge habits. My concern was evident (as was my curiosity), and I took a few private minutes to dive into a discussion about my findings—not my suspicion as to the diagnosis, but my findings.

After some gentle probing, the patient embarrassingly confessed to her bulimia habit, which clearly wasn’t an easy thing to do. Interestingly enough, I got the vibe that she needed or wanted to tell someone about what was going on in her life, and that window of opportunity presented itself by way of a dental visit.

Managing the patient’s dental condition was one thing; helping her toward recovery was another. I reassured her that her oral condition was manageable, but the status quo needed to change. I told her I would be happy to assist her in the process. I sensed relief and gratitude on her part. Sometimes, the starting point in the recovery process can be the hardest hurdle to overcome.

How the dental professional can help

As health-care providers, we’re in a position to assess our patients’ health far more often than our general practitioner colleagues in medicine, due to the frequency in which we see our patients—at intervals of three, four, or six months. Addressing simple questions, such as medication updates and history of surgeries, taking temperature and blood pressure readings, and observing pathological findings both intra- and extraorally all present a vast opportunity for us to diagnose and guide patients down the proper treatment path before their issues develop into something more complicated or severe. Eating disorders are no exception—specifically bulimia nervosa (BN) and anorexia nervosa (AN).

Defining eating disorders

By way of definition, BN is characterized by eating or binging on mass quantities of food/calories in a short period of time, and then purging or eliminating it from the body. This takes place more often in the form of vomiting, but the use of laxatives is also common. In 2015, it was estimated that 3.6 million people had BN, and women—particularly young adult women—were nine times more likely to be affected than men.1

AN is an eating disorder characterized by low weight, food restriction, fear of gaining weight, and a strong desire to be thin.2 The numbers for those with AN are slightly less, with 2.9 million individuals diagnosed in 2015.2 The progression to malnutrition has the potential to affect every organ system in the body, and if severe enough, starvation and death can result.

There is a genetic predisposition for both BN and AN.1,2 Additionally, both disorders are classified as compulsive psychological disorders affecting individuals’ perception and relationship with their body and food, which results in distorted eating behaviors and habits.

Hurdles and stats

Social media platforms and society’s expectations have impacted the perception of what is considered “ideal” for bodily appearance.

One study reported that dentists’ and dental hygienists’ general knowledge of BN and AN was very limited with regard to clinical signs and symptoms, systemic health problems, and, subsequently, treatment and care modalities for these patient populations.3 It was further noted that several accredited dental and dental hygiene curriculums offer very little to no instruction on these issues.3 While these disorders warrant detailed and in-depth discussions, having a general knowledge of signs and symptoms of the systemic and oral implications is mandatory.

Tables 1 and 2 list highlights to consider with regard to medical and psychological complications from eating disorders, especially with regard to BN and AN.

Identifying patients

A dentist’s role in the diagnosis and management of patients with eating disorders can range from simple to complex, depending on the patient, disease severity, and the patient’s commitment.5 As the tendency to hide eating disorders is a conscientious, daily effort, we must take a nonjudgmental and sympathetic approach to communicating with patients about our clinical findings and concerns. Denial, feigned ignorance, embarrassment, and completely clamming up can be common reactions to initiating discussion. Establishing rapport and trust with suffering patients can be key to treatment of the disorder and patient recovery.

Identifying individuals with eating disorders can be a challenge. In light of this, the Sick, Control, One stone, Fat, Food questionnaire (SCOFF) was designed to aid in the diagnosis of patients with potential eating disorders. If a patient responds “yes” to two or more of the five SCOFF questions, there is a strong likelihood that an eating disorder exists.6

SCOFF questions

- Do you believe that you are fat when others say you are thin?

- Do you worry that you have lost control over how much you eat?

- Do you make yourself vomit because you feel uncomfortably full?

- Would you say that food dominates your life?

- Have you recently lost more than 15 pounds in a three-month period?

Oral manifestations and health management

See Table 3 for additional typical dental/oral findings for BN and AN.

Considerations for restorations and oral health management should be timed and aligned with the care and supervision of a medical provider. Medication—usually antidepressants for bulimia—may influence salivary flow5 and give rise to other cause-and-effect oral manifestations.

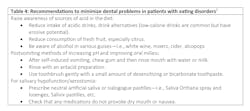

Table 4 outlines recommendations for anorexic and bulimic patients to help with pain relief, sensitivity, and working toward a better appearance.5

Conclusion

Sometimes we need to take a moment from the scheduled mayhem in our practices to purposefully look for issues and have candid discussions with our patients when we see something out of the ordinary that makes us suspect complications in oral health, psychological well-being, and/or systemic health. Our position in the health-care profession is unique in that it allows us the opportunity to detect early signs and symptoms of eating disorders. We can then initiate conversations with our patients, direct them to the proper medical personnel, and be part of a collaborative team that provides the supportive environment these patients need to keep them from venturing down the road to further destruction. A general knowledge of eating disorders is crucial for the diagnosis and care of affected patients, as considerations for relapse prevention, outside support systems, and continued oversight are recommended.

References

- Bulimia nervosa. Wikipedia. Updated June 18, 2020. Accessed June 15, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bulimia_nervosa

- Anorexia nervosa. Wikipedia. Updated June 18, 2020. Accessed June 15, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anorexia_nervosa

- Sturdevant CM, Roberson TM, Heymann HO, Sturdevant JR. The Art and Science of Operative Dentistry. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby-Year Book; 1995:189-190.

- Douglas L. Caring for dental patients with eating disorders. Nature. 2015;16-20. https://www.nature.com/articles/bdjteam20159.pdf

- Milosevic A. Eating disorders and the dentist. Br Dent J. 1999;186(3):109-113. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.4800036

- Roberts MW, Hicks TM. Warning signs. Dimens Dent Hyg. 2014;12(7):60-63. https://dimensionsofdentalhygiene.com/article/warning-signs/

Editor's note: This article originally appeared in Breakthrough Clinical, a clinical specialties newsletter from Dental Economics and DentistryIQ. It has been updated as of December 2024.

About the Author

Stacey L. Gividen, DDS

Stacey L. Gividen, DDS, a graduate of Marquette University School of Dentistry, is in private practice in Montana. She is a guest lecturer at the University of Montana in the Anatomy and Physiology Department. Dr. Gividen has contributed to DentistryIQ, Perio-Implant Advisory, and Dental Economics. You may contact her at [email protected].