Focus on Dental Caries Management

A new medical model for managing caries has emerged. This new model allows dentists to integrate prevention and treatment into minimally invasive caries management and control for their patients. Even though U.S. reimbursement systems lag in their support for optimal care, we can now provide better oral health for patients.

A paradigm shift has occurred in addressing both oral bacteria and remineralization, which includes use of new tools and technologies. Utilized together, enhanced new technologies will facilitate expanded diagnostic capabilities (see the DIAGNOdent article in this issue of WDJ and the QLF article in the September/ October issue of WDJ) and prevention tools, which will allow dental professionals to prevent and minimize life-long effects of chronic tooth decay. Laser technology and small burs (Fissurotomy Burs, for example) can be used for minimally invasive caries removal and caries prevention on occlusal surfaces. There is promising new data on the use of lasers to alter the composition of enamel for caries resistance, but this needs further research. Finally, minimally invasive preparations and restorations are becoming normative in the treatment of caries.

This article is the first in a three-part series which synthesizes new information on the etiology of dental caries, new diagnostics, and minimally invasive dentistry.

The dental profession's understanding of caries and its treatment has been evolving as new diagnostic devices and preventive techniques are introduced to our practices. In 2001, the National Institute of Health's (NIH) Consensus Conference on the Diagnosis and Management of Dental Caries Throughout Life concluded the following:

"Dental caries is an infectious, communicable disease resulting in destruction of tooth structure by acid-forming bacteria found in dental plaque, an intraoral biofilm, in the presence of sugar. The infection results in the loss of tooth minerals that begins with the outer surface of the tooth and can progress through the dentin to the pulp, ultimately compromising the vitality of the tooth."1

This statement combines a number of new components from the traditional approach taught over the last 20 years in dental schools. Our patients assume that tooth decay is caused by eating sugary foods, not that dental caries is an infectious, communicable disease caused by acid-forming bacteria. Patients, along with us, have the opportunity to look anew at how we diagnose, prevent, and treat caries. The conference findings state:

"In order to make continued progress in eliminating this common disease, new strategies will be required to provide enhanced access for those who suffer disproportionately from the disease; to provide improved detection, risk assessment, and diagnosis; and to create improved methods to arrest or reverse the noncavitated lesion while improving surgical management of the cavitated lesion."

Dentistry is moving from the surgical model for preventing tooth decay (placing restorations) to identification of early carious lesions and treating them with nonsurgical methods, including remineralization. One can place a number of restorations in the mouth without treating the underlying disease. The bacteria remain in the plaque biofilm on the remainder of the teeth, capable of creating new areas of decalcification and cavitation. Patients are beginning to expect that we can treat this disease or at least provide them with a reason why they or their children continue to have carious lesions. From an early infectious disease, caries becomes a lifelong chronic disease to be treated continuously.

Dental caries arises from an overgrowth of specific bacteria that can metabolize fermentable carbohydrates and generate acids as waste products of their metabolism. Streptococci mutans and Lactobacillus acidophilus are the two principal species of bacteria involved in dental caries and are found in the plaque biofilm on the tooth surface.2,3,4 When these bacteria produce acids, the acids diffuse into tooth enamel, cementum, or dentin and dissolve or partially dissolve the mineral from crystals below the surface of the tooth. If the mineral dissolution is not halted or reversed, the early subsurface lesion becomes a cavity. These early subsurface lesions are not detectable with our current technology. We are currently able to detect early "white spot" lesions on visible surfaces of enamel, and if these are allowed to progress, frank cavitation will result.

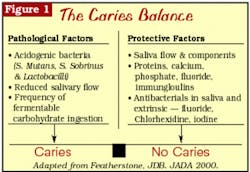

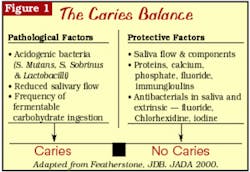

The tooth surface undergoes demineralization and remineralization continuously, with some reversibility. The hydroxyapatite crystals dissolve to release calcium and phosphate into the solution between the crystals. These ions diffuse out of the tooth, leading to the formation of the initial carious lesion. The reversal of this process is remineralization. Remineralization will occur if the acid in the plaque is buffered by saliva, allowing calcium and phosphate present primarily in saliva to flow back into the tooth and form new mineral on the partially dissolved subsurface crystal remnants.5 The new "veneer" on the surface of the crystal is much more resistant to subsequent acid attack, especially if it is formed in the presence of sufficient fluoride. The balance between demineralization and remineralization is determined by a number of factors. Featherstone describes this as the "Caries Balance," or the balance between protective and pathological factors (see Figure 1).6

null

The NIH Consensus Conference on Dental Caries concluded that dental caries is an infectious, communicable disease. Detectable levels of Streptococcus mutans occur in children's mouths after the eruption of the first primary tooth. The source of infection appears to be the mother or other adult caregivers.7 A number of studies have found that mothers with high concentrations of salivary Streptococci mutans tended to have highly infected children.8 These children also had a greater risk of developing a large number of carious lesions in their primary teeth.9,10 Mothers with low levels of salivary Streptococci mutans had children with below threshold levels. Brambilla and others demonstrated that by using a mouthrinse protocol to reduce maternal Streptococci mutans levels starting at six months of pregnancy up to delivery, mothers were able to delay the colonization of bacteria in their children's mouths.11 (A new test for assessing Steptococci mutans is available to dentists for about $40.) Xylitol use can also markedly inhibit recolonization of cariogenic bacteria. Xylitol in gum and mints has been shown to be successful in caries management around the world. Informed by this evidence, we can now begin to help prevent or reduce the risk of caries in children.

One of the popular approaches to caries prevention is to develop a caries risk assessment approach for treating patients. This would involve identifying patients with an elevated series of risk factors for developing caries and providing them with more intensive preventive therapies. Risk assessment can be as simple as noting that a patient has developed one or more carious lesions within one year and then increasing recall frequency, reviewing home care, etc. Understanding the "Caries Balance," as illustrated in Figure 1, can facilitate the development of a more sophisticated approach to caries risk assessment. The following variables should be assessed in developing an overall assessment of caries risk:

- Number of decayed, missing, or filled teeth

- Number of new carious lesions within the past year

- Frequency and timing of ingestion of fermentable carbohydrates

- Elevated levels of Streptococci mutans and Lactobacilli in saliva

- Salivary flow rate and salivary minerals

- Lack of fluoride in the drinking water and use of fluoridated toothpastes

- Poor oral hygiene at-home care

- Presence of heavy plaque on teeth

- Presence of intraoral appliances

- Presence of white-spot lesions

- For infants, we need to assess these same factors in the mother and/or caregiver(s)

If a number of these factors are present, then considering how we can help our patients can reduce their risk for dental caries.

We must first assess which of these factors are significant in increasing our patient's risk for caries. In some instances, reduced salivary flow rates (such as Sjorgen's Syndrome) may dramatically increase the caries risk. In other situations, poor oral hygiene, poor diet, and lack of fluoridated toothpastes may increase risk. There is no correct ranking in order of importance for these risks, but there are a number of papers on caries risk assessment that bear further review.12,13,14 One of the most recent caries risk assessments was published in the Journal of the California Dental Association in 2003.15 It provided both a template for caries risk assessment and some educational tools for patients. This can give you a starting place for creating your own series of tools and assessments for your practice.

There are a number of preventive tools we can use. The most obvious is proper brushing with a fluoridated toothpaste. We can also:

- Modify diet

- Use fluoride rinses and lozenges

- Use high-concentration fluoride toothpastes or varnishes

- Use sugar-free mints, especially those containing Xylitol

- Schedule more frequent recall appointments

- Use antibacterial mouthrinses, including those containing chlorhexidine gluconate

- For dry mouth, use baking soda-containing toothpastes or rinse with a baking soda suspension

These are the current tools we can use. More sensitive and specific technologies are likely to be used in the near future in combination with these tools. (See the DIAGNOdent article in this issue of WDJ and the QLF article in the September/October issue of WDJ.) There is some discussion in the literature about the use of 10 percent povidone iodine, which could be applied topically every two months to reduce the incidence of caries in high-risk children.16 Antimicrobial therapy may also help to reduce Streptococci mutans levels and thus reduce caries and the risk of transmission.17

In addition to developing more preventive tools, more sensitive diagnostic systems must be developed to identify early lesions before cavitation and even before the formation of a white-spot lesion. The Third Indiana Conference on Early Detection of Dental Caries18 provided an opportunity to examine a number of new systems for early detection of caries. There are several new diverse techniques for detection ranging from the use of ultrasonic waves, polarized optical coherence tomography, photothermal and laser luminescence, fiber-optic confocal microscopy, and infrared thermographic imaging. A number of these techniques involve the use of infrared or near-infrared lasers to examine the tooth. Some appear to be more accurate than visual or radiographic methods (our current tools) without the limitations or potential harmful side effects of dental radiographs.

Much remains to fully understand the pathogenesis of dental caries. Currently, the accuracy and validity of any caries risk assessment is only as good as the clinical and diagnostic skills of the clinician. We need to be aware that conditions in our patient's mouths may change or their habits may change, which will necessitate a re-evaluation of their risk for developing caries. We can educate our patients to dissuade them from false assumptions that they will always be caries-free or that they only need to come in for dental checkups at infrequent intervals. Dental checkups not only involve assessing caries, but other factors that are important to our patient's overall oral and general health. Caries risk assessment will help you to identify those patients who need more attention and possibly more intensive preventive therapy. Patients are expecting us to provide them with more information and more therapeutic approaches to the management of carious lesions. Caries risk assessment is one of these approaches.

In the next issue of WDJ, we will focus on early intervention for remineralization of caries combined with new diagnostic techniques. Part 3 of this series will address minimal intervention and materials.

References

1 NIH Consensus Development Conference on Diagnosis and Management of Dental Caries Throughout Life March 26-28, 2001. Journal of Dental Education 2001; 65.10:1162.

2 Van Houte J. Bacterial specificity in the etiology of dental caries. Int Dent J 1980; 30:305-326.

3 Van Houte J. Role of microorganism in the caries etiology. J Dent Res 1994; 73:672-681.

4 Featherstone JDB. The caries balance: contributing factors and early detection. J of CDA 2003; 13.2:129-133.

5 Melberg JR. Remineralization: a status report for the American Journal of Dentistry, Part 1. Am J Dent 1988; 1.1:39-43.

6 Featherstone JDB. The science and practice of caries prevention. JADA 2000; 131:887-899.

7 Berkowitz RJ. Acquisition and transmission of mutans streptococci. J of CDA 2003; 31.2:135-138.

8 Caulfield PW. The fidelity of initial acquisition of mutans streptococci by infants from their mothers. J Dent Res 1995; 74:681-685.

9 Kohler B, Andreen I, Jonsson B. The earlier the colonization by mutans streptococci, the higher the caries prevalence at 4 years of age. Oral Microbiol Immunol 1988; 3:14-17.

10 Caulfield PW, Cutter GR, Dasanayake AP. Initial acquisition of mutans streptococci by infants: evidence for a discrete window of infectivity. J Dent Res 1994; 72.1:37-45.

11 Brambilla E, et al. Caries prevention during pregnancy: results of a 30-month study. JADA 1998; 129:871-877.

12 Krasse B. Caries risk: a practical guide for assessment and control. Chicago, Quintessence Books 1985:7.

13 Anusavice K. Clinical decision-making for coronal caries management in the permanent dentition. J Dent Edu 2001; 65.10:1143-1146.

14 Tinanoff N, Douglass JM. Clinical decision-making for caries management in primary teeth. J Dent Edu 2001; 65.10:1133-1142.

15 Featherstone JDB, et al. Caries management by risk assessment: consensus statement, April 2002. J of CDA 2003; 31.3:257-269.

16 Den Besten PK, Berkowitz RJ. Early childhood caries: an overview with reference to our experience in California. J of CDA 2003; 31.2:139-143.

17 Slavkin HC. Streptococcus mutans, early childhood caries, and new opportunities. JADA 1999; 130:1787-1792.

18 Stookey GK. Early caries detection — future considerations in Early Caries Detection III Proceedings of the 6th Annual Indiana Conference, May 2003, Stookey, GK, editor, in press.

Stephen H. Abrams, DDS Dr. Abrams is a partner in a group practice in Toronto, Canada. He is collaborating on the development of a laser-based system for caries diagnosis. He founded Four Cell Consulting which provides advice to dental manufacturers. Contact him at dr.abrams [email protected].

Margaret I. Scarlett, DMD Dr. Scarlett is the founding editor of Woman Dentist Journal. An accomplished clinician, scientist, and lecturer, she is retired from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. You may contact Dr. Scarlett by email at [email protected].