How To Steal More Than Half A Million From a Dentist

by David Harris, MBA, CMA, FICB, CD, TEP

Licensed Private Investigator

The man I will refer to as Dr. Smith was sitting in a leather chair in his attractive reception area. He was a well-dressed, distinguished-looking man who appeared every bit like the highly respected dental specialist he is. He is in the prime of his career and very obviously accustomed to being the master of his domain.This day, however, it was evident that things were not well in Dr. Smith’s kingdom. He was agitated and obviously resentful of the intrusion I was making into his life. “You’ve made a mistake,” he told me. “This can’t be true.”There was no mistake — the news I had just given him was accurate. His trusted office manager of nearly 20 years had been stealing from him. On receiving this information, Dr. Smith leaned forward, placed his head in his hands, and fell silent.Allow me to introduce myself. My name is David Harris. I am a licensed private investigator and run a company called prosperident. It is the only company in North America specializing in preventing, detecting, and remediating frauds committed against dentists.I love my job. Sure, sometimes I come face to face with some pretty distraught people, but finding fraud is like trying to complete a big jigsaw puzzle while someone keeps hiding some of the pieces from you. The feeling you get when you outwit them is like the one you get when you sink a 40-foot putt.Although we didn’t know it yet, Bill Hiltz (prosperident’s chief forensic examiner) and I were just beginning to investigate what would become one of the largest dental fraud cases ever. The chain of events that brought me to Dr. Smith’s office began a month earlier, when Dr. Smith and his colleagues hired a practice-management consultant. The consultant, an experienced former dental office manager, was hired by Dr. Smith and his colleagues over intense objections by his office manager, who we will call “Mary." In fact, Mary threatened to quit if the consultant was brought in.This seemed unusual to the consultant, and she called Bill Hiltz of my office to discuss her concerns. Bill reminds me of a bloodhound — he has a “nose” for fraud and it was twitching like the gearshift of an old Ford when the consultant described Mary’s behavior. Bill quickly arranged to visit the office after hours (when it was unlikely that Mary would be there) to do what we call a “fraud probe.” He also brought along his good luck charm, yours truly.It took us less than an hour to find fraudulent activity to validate Bill’s suspicion; although, at that time, we had no inkling that what we were seeing was the tip of the iceberg. We then reported our initial findings to Dr. Smith, the managing partner of the office, which prompted the scene of disbelief that I described at the beginning of this article.I’m a pretty persuasive guy, especially when I know my poker hand has four aces, and it still took a lot of effort to convince Dr. Smith that his office manager was a thief. Dr. Smith’s disbelief was not surprising when you consider that Mary had years to shape his perception of his office finances. For example I showed Dr. Smith that his bank deposits over the last year included virtually no cash, sometimes with weeks between cash deposits. Dr. Smith’s reply was that “most of our patients don’t pay with cash anymore; they use a debit or credit card,” which was exactly what Mary wanted him to believe.In fact, some patients still preferred to pay in cash — to the tune of about $6,000 per month. The problem was that Mary recorded less than $1,000 a month and pocketed the rest!I should tell you a bit about Mary. She had worked in the practice for 20 years, spending the last 10 as the office manager. She certainly didn’t have an extravagant lifestyle — she drove an old car and, from appearances, got her clothing at Walmart. In the eyes of Dr. Smith, she was incredibly efficient, loyal as a puppy dog, and had an enviable work ethic — she routinely stayed late in the office and often came in on Saturdays to “stay on top of things.” She rarely took vacations and hadn’t taken a sick day in anyone’s memory. She enjoyed the complete trust of Dr. Smith and the other dentists, and worked to create an environment where the dentists could focus on their clinical responsibilities, confident that the adminstration of the practice was in capable hands.Mary’s husband had died about five years earlier. She has an adult son, who had a drug problem and was, as they say, “known to police.” Mary’s son lived with her. When we find the “smoking gun” conclusively establishing fraud, we initiate a procedure known as “lock down.” This involves changing passwords and locks, taking steps to preserve the evidence, and of course buying the “perp” a bus ticket to Unemploymentville. Dr. Smith was visibly torn between the convincing evidence we gave him and his loyalty to a respected, long-term employee. He reluctantly agreed to let us implement the lock-down protocols.Once the thief is caught and the evidence is protected, we move from “probe” to “investigation.” This is where we start looking into each corner of the practice’s operations to see if we can find fraudulent activity. With Mary safely out of the way, we began looking at the computer, banking, and accounting records of the practice. And we found a lot!At this point I should tell you about the two types of thieves in dental offices. There is a group of people (we label them the “dishonest”) who are career criminals who happen to target dentists. These folks get hired and typically commence stealing right away. When they get caught or their background catches up with them (and it normally doesn’t take long), they simply move on to another practice and start stealing there. When they get too well known in a city, they either make a career change (i.e. target some other profession) or move to another town where their reputation doesn’t precede them. While these people can make an enormous mess in any practice they work in, the damage is constrained by the short time period they typically manage to last in each office before being caught.The far more dangerous group in my view is the second group. These people (who I call the “desperate”) work in a dental office, typically for quite a few years, when they become desperate for money. This could happen for many reasons: their spouse could lose his or her job, they might have some type of addiction, they could be experiencing matrimonial problems, etc. Once the Desperates have exhausted their other options for money, it dawns on them that stealing from you would be pretty easy. And so it starts.Some time ago (about five years earlier, as best we can figure), Mary became one of those Desperate people. We’re not really sure why — this was about the time her husband died (and possibly the loss of his income and eventual pension might have been a factor). We think Mary’s son needed money to cope with his considerable legal issues (and probably to pay for his habit). What we do know is that when Mary began to steal, she did it cleverly. Her methodologies varied a bit over time, but in most months, she managed to slide about $9,000 unauthorized (and also tax-free) dollars into her pocket.So how did she do it? The office had the usual controls that haven’t changed much in dentistry since the 1950s. This is something that dentists proudly tell me when I bring up the topic of fraud. They explain that their office does its day-end balancing religiously, as if this will somehow protect them from fraud.I then have the job of giving these dentists the bad news — only the most amateurish of criminals will take cash from the bank deposit without adjusting the records to make the day-end procedures balance. Also, this balancing is normally done by the receptionist or office manager (the very person who, if committing fraud, is unlikely to blow the whistle on themselves) without any particular oversight on the part of the dentist. Like most professions, fraud against dentists has gotten better over time; bypassing this day-end process is pretty simple for most thieves, and thefts not involving stealing cash are pretty common.Mary had a duffle bag full of tricks in this area. Some of her favorites were:1. Lapping — This is where one patient pays cash, which is then pocketed by Mary. She then finds an insured patient, “upcodes” the treatment when billing the insurance company, and applies the excess to cover the account of the patient from whom she stole cash.2. Write-offs — During Mary’s last year as office manager, the office wrote off about 10% of its total revenue. While a small portion of this was undoubtedly legitimate, the majority of write-offs were used to cover the records of accounts from which Mary had “borrowed.” Often, this would be combined with lapping — i.e., Mary would steal from Patient A’s account, find Patient B, a patient who was a good candidate for a write-off (e.g., moving away and unlikely to return), take the money paid by Patient B to cover the account of Patient A, and then write off the balance of Patient B’s account.

3. Nonentry — To bypass the computer system, Mary would sometimes issue hand-written receipts to patients, explaining that the computer was down or the printer wasn’t working. This would give her unaccounted-for funds that she could steal or lap to cover other thefts.

4. Payroll — Mary was in charge of payroll, and increased her pay to reflect 12 overtime hours weekly at time and a half. Dr. Smith was vaguely aware that Mary was being paid for some extra hours, but he didn’t realize that it was at a premium rate or that what Mary was doing during these well-paid extra hours was stealing from him and his associates.

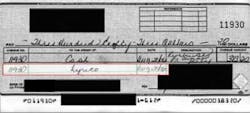

5. Fraudulent disbursements #1 — This is where Mary was particularly creative.There were three dentists practicing together in this group. Each dentist maintained his own revenue account, into which his income was deposited. There was also a “common” account that was used to pay the rent, supplies, staff, etc. Mary had signing authority on the common account. Mary would write checks payable to “cash,” typically on a monthly basis. The office used a one-write system for checks, where a carbon-paper strip on the back of the check was used to record the details of the check on a check ledger. Mary would doctor the check ledger so that the check would appear to be for some other purpose. Figure 1 below is an example of Mary’s tampering.The lighter colored insert is the check ledger corresponding to this check, which has been altered. When the bank statement came in, Mary would destroy these checks.

Figure 1 -- Example of actual check and tampered ledger entry

6. Fraudulent disbursements #2 — Mary would give each dentist a monthly accounting of expenses, and each dentist would make a deposit to the common account for his share. Mary would steal from the account of a patient of one of the dentists, and then cover the theft by drawing a check on the common account. She would then include this amount (appropriately camouflaged, of course) in the monthly accounting that she gave to the dentists, so that they would reimburse it. In effect, the dentists themselves would cover these thefts, routed through the common bank account.

As our investigation continued and these details unfolded, it began to sink in with Dr. Smith and his colleagues that Mary had been coldly, systematically plundering their wallets. Mary used the trust that they had given her — and her knowledge of the items to which the dentists were attentive and inattentive — to steal large amounts of money and avoid detection for an extended period. When Dr. Smith realized this, the initial disbelief that he had felt when we first broke the news to him turned to disgust and anger.

At this point, Dr. Smith had only one question: “How much money?” he asked in a voice barely above a whisper. We told Dr. Smith that we had identified $609,000 in theft, and that there was probably more, but that it would serve no purpose to expend the efforts needed to find the remainder.

Mary has recently been charged with a criminal offense, but it is unlikely that she will do much jail time. I should tell you one other thing about Mary. After she “left” Dr. Smith’s office, she passed her seemingly attractive resume all over Dr. Smith’s city. I still have a copy of it in my office. I particularly like the part where she refers to her honesty, integrity, and familiarity with computers. She did actually manage to get hired at one dental office, but we made the local Dental Board aware of her past and that seemed to shut down her efforts to secure another “high paying” position in a dental office. One thing that this case did confirm for me is that dentists need to be better at doing background-checking and verifying resumes.

So what can we learn from this episode? I can think of several things:

1. Know your employees and their problems — be vigilant for employees desperate enough to become thieves.

2. Watch for patterns of behavior consistent with fraud — a full discussion of these patterns would probably be a great topic for a future article, but an employee refusing to take vacation is a sure sign of trouble, as are employees who are frequently in the office alone at odd hours.

3. Scrutinize resumes forensically:

a. Check references, but don’t use the phone numbers helpfully provided. Look them up yourself so you will know that you are really talking with the reference and not some friend of the prospective employee on a disposable cell phone.

b. Look for inconsistencies — Ask previous employers where the applicant worked before and compare the answer with what's on the resume.

c. Ask former employers to confirm exact dates of employment — applicants sometimes try to cover a checkered past by “stretching” the dates of favorable employment experiences.

4. Investigate your suspicions — that “spidey sense” that tingles about fraud is right more often than not. The number of times we get a phone call from a worried dentist where that suspicion subsequently turns out to be unsubstantiated is quite low.

Well – the phone’s ringing, so I better grab it. Until next time ...

David Harris is the president of prosperident, the only company in North America specializing in fraud prevention, detection and remediation. Bill Hiltz iis prosperident's chief forensic examiner. Harris and Hiltz have spoken at national, international, and regional conferences on fraud.They can be reached by phone at (902) 422-0592 or by e-mail at [email protected].