Ergonomics ... How does dentistry fit you?

Dentists are at high risk for musculoskeletal disorders due to the nature of their work. The key to preventing work-related musculoskeletal disorders is ergonomics — the science of fitting the work environment to the worker.

Every 10 seconds, a worker is temporarily or permanently disabled. While it is easy to visualize a carpenter falling off a roof or a farmer getting caught in a combine, the reality is that many work-related injuries occur while the worker is simply sitting in an office chair — or on a dental stool. These injuries may take longer to cause, but the results can be just as devastating.

Musculoskeletal disorders (which include repetitive-motion disorders and conditions such as carpal tunnel syndrome and hand-arm vibration syndrome) are among the most common medical problems, affecting at least 7 percent of the population and accounting for 14 percent of all doctor visits. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders make up 34 percent of lost workday injuries. These are the injuries that result from repetitive work, awkward or constrained postures, heavy lifting, pinching grasps, forceful movements, and vibrating tools. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders are the nation's leading job-safety problem, causing more than 600,000 workers to lose work time each year and costing an estimated $15 to $20 billion in worker compensation costs and lost productivity. (For more information, visit www.cdc.gov/niosh/muscu-cd.html.)

Dentists are at high risk for musculoskeletal disorders due to the nature of their work. Musculoskeletal pain is more frequently noted by oral health providers than any other occupational hazard, including communicable diseases and other physical and emotional disorders. A survey published in the Journal of the California Dental Association in February 20021 found that 61 percent of dentists surveyed said they had experienced work-related neck pain during the year; 51 percent reported lower-back problems; 44 percent said they had shoulder pain; 43 percent had upper-back pain; 38 percent reported hand pain; 30 percent mentioned mid-back pain; 14 percent indicated arm pain; and 10 percent reported leg pain.

Dentists lose millions of dollars a year because they have to cancel patient appointments or can't work due to musculoskeletal pain. In 19872 alone, dentists had to cancel 1.3 million patient appointments and lost income amounting to $41 million — more than $65 million in today's dollars. (At press time, more recent statistics could not be located. Obviously there is need for additional study in this area.)

Women suffer higher rates of work-related musculoskeletal disorders, in part because their jobs require the kinds of activities that cause these problems. Women make up only 46 percent of the workforce, yet they account for 62 percent of the work-related cases of tendonitis and 70 percent of carpal tunnel cases. According to OSHA, each year more than 100,000 women experience work-related back injuries that cause them to miss work.

One thing that all experts (including OSHA) seem to agree on is that the key to preventing work-related musculoskeletal disorders is ergonomics — the science of fitting the work environment to the worker. Ergonomics is a critical issue for women because the traditional one-size-fits-all approach to workplace design has been based largely on an average for male workers. This means that women often must function in work environments that have not been adapted to their size and shape. It is exactly this kind of situation that can lead to musculoskeletal injuries.

Most dental equipment, operatory layouts, and procedure techniques were developed with an average male dentist in mind (the average man being about 5'10"). As a result, female dentists have been forced to adapt their (usually) smaller and differently shaped frames to a workplace environment designed for a man (average height for a woman is 5'5 1/2"). This is a tremendous oversight when one considers that in the average four-operatory dental practice there are two hygiene rooms, two operative dentistry rooms, and three practitioners (one dentist and two hygienists).

If we assume that approximately 98 percent of hygienists are female and 21 percent of dentists are female, that means that over 70 percent of the time the clinician rolling up to the dental chair is a woman, not a man. So the "average" practitioner is, in fact, female. Regrettably, the dental industry has been slow to catch on.

"We learn to compromise and put ourselves in positions that feel comfortable," explains Elizabeth B. Lewis, DDS, of the Indy Dental Group, Indianapolis, Ind.

At 5'6", Dr. Lewis is of average size for a woman, which is shorter than the typical male. Like many other women dentists, she finds that sometimes she must adjust her body to fit a work situation. This is the opposite of ergonomics, which has as its goal adapting the worker's environment to fit the worker.

It is difficult to say just how large a problem work-related musculoskeletal disorders are for women dentists. Studies of dentists tend to involve primarily or exclusively male subjects. A study in Australia3 that did include women dentists found that 82 percent of all respondents reported experiencing one or more musculoskeletal symptoms during the previous month. Fewer women than men reported having no symptoms. Female dentists also were more likely to report frequent pain and headaches and to rate the severity of their most severe symptom higher than the male dentists did.

There have been a number of studies done on dental hygienists, a population that is overwhelmingly female. Although the tasks performed by hygienists are different, studies of this group may be a good indication both of the risks involved with the types of motions female dental professionals make and of the effects on women of using dental tools in a work environment designed primarily for men.

A study published in the September 2002 issue of the American Journal of Industrial Medicine4 found that a large percentage of dental hygienists reported work-related musculoskeletal disorders, especially in the wrist, neck, and upper back. In fact, more than 90 percent had experienced at least one musculoskeletal complaint in a 12-month period.

The study's authors concluded that their findings "emphasize the need for ergonomic intervention in the dental hygiene profession, including education, modification of instruments, and flexibility in scheduling patients."

One common problem women dentists face is something a male dentist never even thinks about. "The biggest thing is, as women, we end up working far closer to the patient than makes us feel comfortable," explains Dr. Lewis. "I don't feel comfortable putting my chest in the patient's face, so I tend to sit back."

While the tendency might be to offer an uncomfortable chuckle at this point, the facts are not so funny. If the doctor isn't close enough to the oral cavity, she must lean forward, which results in awkward head posture. When the head is pushed forward, the weight of the head on the neck increases by about 300 percent. This can lead to chronic muscle problems in the upper back.

Dr. Lewis also finds it hard to get the patient chair low enough.

"We have to lift our stool higher to compensate," says Dr. Lewis, "so we lose the 90-degree angle for our knees."

Unfortunately, these are just the kinds of compromises that force the body into positions that can cause problems. "We all have back problems and neck pains," admits Dr. Lewis. "It's so prevalent in our profession."

Dentists also are at risk for carpal tunnel syndrome. This condition occurs when repetitive motions and/or sustained postures damage tissues and cause swelling that puts pressure on the median nerve, which passes through a narrow channel in the wrist called the carpal tunnel. This causes painful tingling, numbness, and loss of grip strength. Women are more likely to develop carpal tunnel syndrome than men, partly because hormonal changes can cause fluid retention, which can be an aggravating factor.

"I know a 38-year-old dentist who had to stop practicing due to carpal tunnel syndrome," says Dr. Lewis. "Even with surgery, she couldn't do it. That's a fear. That's a big fear."

In one study, published in the February 2001 Journal of the American Dental Association5, more than 1,000 dentists were tested at American Dental Association Annual Health Screening Programs in 1997 and 1998. The study's authors, from the School of Public Health at the University of Michigan, diagnosed median mononeuropathy (disease, inflammation, or damage to the median nerve) in 13 percent of the dentists using electrodiagnostic techniques.

However, only 32 percent of those dentists reported symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome. The authors concluded that although dentists had a higher rate of carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms than the general population, when electrodiagnostic measures were used, the prevalence was determined to be nearly the same.

The authors stated that early recognition of carpal tunnel syndrome can lead to more effective manage-ment and that education regarding ergonomic risk factors can be an effective preventative. There is a need for additional study, particularly to determine the carpal tunnel risk for women dentists.

Dr. Lewis speaks for many women dentists when she says: "There is a need for manufacturers to provide a broader range of settings and positions for dental equipment."

Dentists want to provide good patient care and run a productive, profitable practice, but it's difficult to do that when their hands go numb and their backs are seized with pain.

The answer can't be simply to cut back on work, yet that's a path many dentists are being forced to take. Dr. Lewis, for example, has begun to limit some procedures. "I can only do so much hygiene in a day," she says. "I just don't have the strength in my hands anymore."

Other dentists have had to reduce the number of hours they work. Some have even been forced into early retirement.

There are things manufacturers can do to help prevent musculoskeletal injuries and to enable dentists to practice without restricting themselves. Most dental equipment manufacturers are working to develop ergonomically designed products. Some are also changing their specifications to make equipment adaptable to people of smaller (or taller) stature. In some cases, though, the solution may require a whole new approach.

Take the lowly dental stool. The basic design of the doctor's stool has remained virtually unchanged for decades. Although the height is adjustable, the range of adjustment in most cases is designed around the male height range.

For this reason, many women dentists have trouble with them. "I always say I need a seat belt on my stool to hold me in," says Dr. Lewis. "I keep sliding forward on it."

When a dentist is seated properly, her legs should be at a 90∞ angle with her feet square on the floor so that her weight is evenly distributed. Unfortunately, if the stool won't go low enough, the clinician will slide up onto the front third of the stool to get her feet on the floor. This puts pressure on the back of the thighs, which restricts blood flow to the legs, causing numbness and potentially creating varicose veins. This position also makes it impossible for the dentist to use the lumbar support properly.

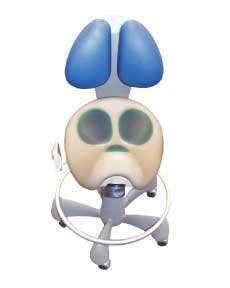

One solution is to find a stool with a shorter lift cylinder so that the stool can be positioned lower. Another is to look at the new generation of ergonomic stools — such as the Dentech Pluto stool (see accompanying photo) — which are designed completely differently. The clinician straddles the stool, which is shaped to cradle the body properly, providing ergonomically correct seating while eliminating many of the pressure points. Like anything new, it takes some adjustment to get used to sitting saddle-style, rather than on a flat stool, but it eliminates the need many women dentists have to brace themselves on the back of the traditional stool for support.

But properly designed equipment isn't enough. Dentists (particularly those outside "average" size ranges) must learn how to adjust the equipment and how to use proper ergonomic techniques to avoid injury. No matter how well-designed a piece of equipment is, if it is not adjusted to the individual who is using it and if that person doesn't use it properly, the ergonomic features may be useless.

At Dentech, we have begun to work with our full-service dealers to provide customers with the knowledge they need to properly use the ergonomic features of our products.

By training our dealers' sales representatives as well as our own, we can build a valuable resource for our customers. The rep then becomes an adviser to the practice, helping dental office professionals reduce the risk of musculoskeletal injuries. The Dentech Inner Circletm Productivity Program (available through Dentech's full-service dealers) offers in-office training in addition to a wide range of resource materials to help dental professionals learn to practice safely and productively. For more information about the program, call (800) 826-5004.

Until dental schools begin to train students in proper ergonomic technique, it will be up to dental manufacturers and dealers to provide the products and the instruction that will help dentists – male and female — deliver good patient care without compromising their own health.

Then, if dentists choose to work shorter hours, it will be because they want to enjoy more time away from the office, not because they are forced to give up practice time due to pain or injury.

References —

- Rucker, et al., "Ergonomic risk factors associated with clinical dentistry," Journal of the California Dental Association, 2002 Feb;30(2): 139-48.

- Shugars, et al., "Musculoskeletal pain among general dentists," General Dentistry, 1987; 535:272-276.

- Marshall, et al., "Musculoskeletal symptoms in New South Wales dentists," Australian Dental Journal 1997; 42:(4):240-6.

- Anton, et al., "Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Symptoms and Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Among Dental Hygienists," American Journal of Industrial Medicine 2002; 42:248-257.

- Hamann, et al., "Prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome and median mononeuropathy among dentists," Journal of the American Dental Association 2001 Feb; 132(2): 163-70.

Steven W. White

Mr. White is president of Dentech Corporation. He has been in the dental industry for 25 years and is a nationally known speaker and author on the subject of ergonomics and productivity in the dental operatory. You may contact Mr. White at (800) 826-5004.

An epidemic of repetitive stress injuries

More than 100 different injuries can result from repetitive motions. The combination of repetitive motions, which cause friction that wear down tissues, and sustained postures that keep the blood supply away from the working tissues, produces damage that builds up until it causes diseases such as carpal tunnel syndrome and tendonitis. The Bureau of Labor Statistics says that cumulative trauma disorder, another name for repetitive strain disorder, is the fastest growing occupational disease, rising from 18 percent in 1981 to 61 percent in 1991.

These kinds of disorders often affect dental professionals, because much of their work involves sustained postures and repetitive motions. In 1990, it was estimated that the annual loss of income to dental practitioners due to cumulative trauma disorder-related pain was more than $41 million.

Repetitive stress disorders have become such a widespread problem that the Healthy People 2010 Objectives for the Nation has as one of its objectives to "reduce the rate of injury and illness cases involving days away from work due to overexertion or repetitive motion." This is a statement of national health objectives designed to identify the most significant preventable threats to health and to establish national goals to reduce these threats during this decade. The Healthy People 2010 Objectives for the Nation, which was developed through a broad consultation process within the Department of Health and Human Services, is built on the best scientific knowledge and designed to measure programs over time. Its target is a 50 percent improvement, which will be achieved when the rate of injuries due to overexertion or repetitive motion is reduced from 675 to 338 per 100,000 full-time workers. The full Healthy People 2010 report can be found on the Internet at www.healthypeople.gov.