Journey of Hope

Some wouldn’t smile. Some couldn’t. But after surgery, the children beamed as if they had been doing so all their lives.

It is said that success is a journey and not a destination. In October 1996, I unknowingly began the journey of my life, and with the help of Rotary, an international service organization, I found success beyond my dreams.

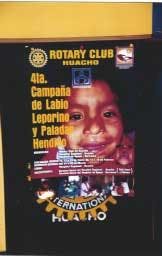

During a presentation at my Rotary Club that told of a group of Rotarians who had traveled to Chile, I learned of the unrepaired congenital facial defects of cleft lips and palates of children in the Andean mountain regions. These children suffer from life-threatening infections, nutritional deficiencies (since eating is difficult), and rejection by their neighbors and families.

I decided immediately that I wanted to volunteer. I had been searching for a way to repay the universe, as it were, for the many blessings in my life, including a gratifying career, and this sounded like the ideal opportunity. The Rotary group turned me away, however. Their quota was full, and I didn’t have enough to offer. They welcomed a financial donation, but that wasn’t what I had in mind.

So, a group of fellow Rotarians and I decided to form our own group. At this point, we had nothing but a vision - no money, no destination, no surgical team. We began raising money with a luau fundraiser I hosted, and it was matched with Rotary grant dollars.

In much of life, we meet with talkers and we meet with doers. I don’t consider myself much of a talker; therefore, I pushed through a series of struggles and with our small group created “Rotocleft.”

I made a discovery trip to Huanuco, Peru, a remote city high in the Andes, during the summer of 1997. I decided that would be the destination for our surgical team to treat the many children I viewed with cleft deformities. Another Rotary group, Operation Condor from Wheaton, Ill., had made two general medical mission trips to Huanuco and formed alliances with local Rotarians, which allowed for communication and arrangements with the local hospital and Ministry of Health.

Coordinating the logistics for our first trip in January 1998 was daunting, but fortunately my four years of Air Force training as a dentist kicked in. There is no better preparation for this kind of fast-paced, complicated project. The medical equipment alone required 63 pieces of luggage for 23 people, about 500 pounds over the airline’s limit for the entire group. We brought our own gowns and masks, medical instruments, antibiotics, sutures, and postoperative analgesics. We even carried an entire MASH (Mobile Army Surgical Hospital) dental unit.

Our team packed most of the supplies into military duffle bags, and we traveled for five-and-a-half hours from Miami to Lima, Peru. Customs can be challenging, but with appropriate documentation, we resumed our journey by bus within a short time. Our bus traveled for 17 hours, delayed by storms and mudslides washing out sections of the mountain road. We arrived in Huanuco close to midnight. The mountain pass at 15,800 feet caused some nausea from altitude sickness, but we were glad to be there despite the delay.

We went to the hospital the next morning, and after absorbing its heartrending condition, we went to work. Nothing can prepare you for your first encounter with a hospital in an impoverished town in the developing world. The Huanuco hospital employees do the best they can, but they face very difficult conditions. There’s no air conditioning, so the windows remain open, making operating conditions less sanitary. Goats live on the hospital grounds. Many of the toilets don’t work. The walls are covered with broken plaster, and hot water is scarce. The medical equipment is outdated or in need of repair. Everything is used and reused until it wears out or breaks down, even the surgical gloves.

Nevertheless, we plunged in, working 14-plus hours per day. Over the course of the trip, we performed 42 operations on 28 patients, from three months to 21 years of age. The surgeons also helped train two Peruvian physicians to perform similar procedures.

The children’s stories were heartbreaking. The local people believe these children are cursed and totally shun them. Sometimes they are even rejected by their families. They suffer from horrible infections. Many have speech impairments and can’t get proper nutrition because of gaping holes in the roofs of their mouths. Most will never marry or have children. All but the most menial of jobs are out of the question.

Primarily, we operated on younger children, because their chances of success are greater. We did, however, perform surgery on a 16-year-old girl, Dalinda, who had a double cleft lip. Normally, this kind of surgery is done in stages, but because we didn’t know if we’d ever see her again, we did it all at once ... in five hours. Dalinda was so ashamed of her appearance that she habitually shielded her face with her hand. We had to convince her to take her arm down long enough to allow us to take a “before” photograph. Dalinda is absolutely beautiful now and is slowly starting to show her face in public. Nobody in her family ever imagined that her condition could be cured.

And then there is my personal hero, Hector. Only 13 years old, Hector walked through the mountains alone for 15 days to reach Huanuco. We’re not even sure how he found out that we would be performing this kind of surgery, since the people in the countryside have no televisions or telephones. Word traveled somehow. Hector arrived the first day of our trip, but we weren’t able to operate on him until the very last day. Still he waited, hopeful and all alone. On our last night, I was in the recovery room with him about 11 p.m. when a woman suddenly showed up at the door and said she was Hector’s tia, or aunt. I brought her inside to see Hector in the recovery room, and we both hugged and cried, overjoyed. I was happy because Hector finally would have family by his side, and she was thankful because her nephew finally would have a future.

Each of the children had his own poignant story. I had never realized before how much power we have to change a life. That’s not to say it is easy. I spend about 400 hours putting together each mission, but this effort on the front end contributes to our success. My past military training has helped me with organizational skills, although team members tell me I am still like a drill sergeant on these journeys.

I credit our teams’ flexibility and great attitude despite adversity for the success of our missions. Also to credit are the Rotarians in Peru who provide great connections. The Peruvians are warm, generous people. They continue to praise us for our detailed organization and high-quality surgical outcomes. We have recently completed our fifth Rotocleft mission with a team of 36 people from four countries.

The team and local people have always worked well together. We try to spend time getting to know the people of Peru, who are gracious and eager to help.

I ask the nurses, doctors, and department heads, “What can we do to work with you?” and “What do you not want us to do?” I try to think of us as guests in their hospital and their country. Even though we are trying to help them, we should never just barge in, but always ask permission first.

I think this cultural sensitivity has also contributed to our success. We have worked well with the hospital staff as a team, and they, in turn, expend so much extra effort. The nurses make just $35 (in U.S. currency) per week, yet they welcome the opportunity to serve us for the welfare of the children.

Our team has been complimented on four of the past five missions with one or more dental teams. This past mission in March 2004 was comprised of three dentists who extracted about 1,000 teeth, did 150 prophies, and provided dental education materials to more than 600 patients in four-and-a-half days.

In January 2005, a team of 31 is scheduled to provide surgical and dental treatment in addition to laying the groundwork for a teaching institute that will serve 200,000 people who currently have no medical or dental care.

Each time I return to the United States, I have a chance to reflect on my purpose for continuing to serve the people of Peru. It is a decision of hard work with no guarantee of reward. However, my teammates and I agree that the experience provides growth for each of us as professionals, as Rotarians, and as human beings.

Ralph Waldo Emerson said, “It is one of the most beautiful compensations of this life that no man can sincerely try to help another without helping himself.”

In the end, I have decided to continue to use my gifts to serve, because it has become a part of me. Dentistry has helped me to grow in more ways than I had ever dreamed.

Sandra J. Lilo, DDS

Dr. Lilo is a long-time member of the ADA, state and local dental associations, and the Rotary Club of Seminole Lake, Fla. Her team leaves for Huacho, Peru, in January 2005. You may contact Dr. Lilo by phone at (727) 398-7473, or by email at [email protected].