Does the light enhance your sight?

Debbie Zafiropoulos, RDH, outlines the limitations of the clinical oral examination and explains why and how emerging oral cancer screening technology should be integrated.

Oral cancer is often preventable, yet the number of diagnoses has not changed dramatically over the past three decades. Many of us are still searching for ways to change the statistic so often used in anti–oral cancer campaigns and educational materials: one person dies of oral cancer every hour.

Unfortunately, the numbers of new cancer cases and deaths in the United States in 2016 can only be estimated because the incidence and mortality data still lags at least two to four years behind, due to the time it takes to analyze, qualify, organize, and disseminate the information.

But do you have to know all of the current statistics to do the right thing? We know our patients are dying of underdiagnosed and undertreated oral diseases.

What can we do about it now? With all of our access to technology, training, and informative articles, why are we still reporting that more than 30% of patients are diagnosed with late-stage oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) and oropharyngeal cancer, even though they received oral cancer screenings within three years of being diagnosed? (1)

How is this possible? Is the clinical oral examination (COE) we were taught in school still relevant, effective, and widely implemented to the utmost standards to ensure patient safety and disease prevention? I would submit that the answer is a dismaying "no." Relying on a subjective, unstandardized, antiquated, and underexecuted clinical oral exam is an inadequate way to prevent such a horrendous disease. Lesions—or as I prefer to call them, abnormalities—are still underdiagnosed, and clinicians' subjective impressions of what they are still lead to many late-stage diagnoses.

The clinical oral examination is considered by many to be the standard of care for detecting abnormal oral mucosal changes, including cancer. It requires a thorough head and neck examination, evaluation of oral mucosa by means of visual inspection under incandescent overhead or halogen illumination, and palpation. (2,3)This is absurd! You cannot detect cancer with a clinical oral exam.

Oops! I stand corrected: you can detect cancer with a clinical oral exam—when it’s too late. You detect it when you palpate something the size of a sesame seed, poppy seed, grain of rice, or bigger, or when you see an abnormal growth that has probably invaded the basement membrane and is in stage III or IV.

Lesion detection and COE protocols are extremely important in getting an abnormal finding to a definitive diagnosis from an oral pathologist. So how do you get started?

The first step is to establish a detailed protocol. Define the objectives of your office's COE or oral abnormality screening. Then practice it with the team! This is very important. Having defined objectives will establish a higher standard of care and open communication with the patients about early detection as the first line of prevention for all patients in your care.

For many years, I've offered prevention therapy and biofilm care protocols through my lectures and training programs, and I have learned that everyone does not see the same, examine the same, or articulate care the same. For this reason I have developed a synchronized training system for clinicians called SOSA, which stands for screening for oral and skin abnormalities. The purposes of SOSA are to synchronize screenings to save lives and to educate the community (including the public) about how self-examination of all skin surfaces, including the epithelium behind the lips, is important.

The patient's risk factors, the clinician's expertise, and the patient's willingness to be examined all affect our ability to screen for abnormalities. The likelihood of a visual exam identifying or ruling out dysplasia, OSCC, or human papillomavirus (HPV) is at best questionable, especially for patients who do not have any recognizable or documented risk factors.

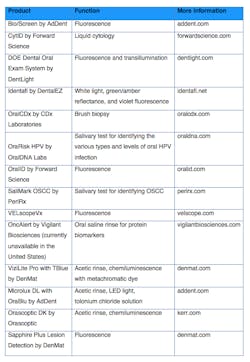

But with the growing number of adjunctive screening tools available, the comprehensive oral exam could become the first line of defense against the mortality and morbidity statistics of oral cancer. I have researched the companies that offer handheld in-office screening tools and those that offer diagnostic kits to help us learn more about what the SOSA examination identifies (table 1).

Please be clear that the light-assisted technologies listed in Table 1 use LED light sources at varying wavelengths. By no means are any of the fluorescence, reflectance, chemiluminescence, or transilluminating systems diagnostic. They are for screening. When used effectively and consistently, they provide more information during SOSA that can assist the clinician in determining what the next step should be.

For example, devices that utilize fluorescence technology emit light in the blue spectrum (400–460 nm), causing fluorophores in the oral tissue to excite and fluoresce. Areas of epithelium that appear to be dark or have reduced autofluorescence should be considered suspicious. Again, this does not mean the patient has cancer; these tools indicate that a more defined and thorough exam is needed. The same is true for the tools that use an acetic rinse to excite the tissues.

Table 1: Adjunctive screening tools, in no particular order

These options also offer more information that qualifies the referral to the specialist for more invasive procedures such as biopsies. Qualifying the referral is our best opportunity to prevent the patient from fearing the worst and falling through the cracks and instead encourage the patient to see the specialist at the referral appointment.

Please, for the lives of those already diagnosed, initiate your protocol for early detection of oral abnormalities. If you do not know where to start, ask me!

References

1. Jemal A, Murray T, Samuels A, Ghafoor A, Ward E, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2003. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53(1):5-26.

2. Epstein JB, Gorsky M, Cabay RJ, Day T, Gonsalves W. Screening for and diagnosis of oral premalignant lesions and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: role of primary care physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(6):870-875.

3. Huber MA, Bsoul SA, Terezhalmy GT. Acetic acid wash and chemiluminescent illumination as an adjunct to conventional oral soft tissue examination for the detection of dysplasia: a pilot study. Quintessence Int. 2004;35(5):378-384.

Debbie Zafiropoulos, RDH, calls Florida home. She is the founder of the OralED Institute, a division of Delta Force Group Consulting. She is also the founder of the National Cancer Network, a 501(c)(3) with a vision of a cancer-free world that aims to raise awareness about prevention, progress, screening, and referrals. With more than 27 years in the health-care industry, she was nominated and selected by her peers at a 2016 recipient of the Sunstar/RDH Award of Distinction. For more information about SOSA training, contact her at (561) 358-7660 or debbiez@debbiezrdh. To join, donate, or support National Cancer Network efforts, visit nationalcancernetwork.org.