Play it SMART: Silver diamine fluoride plus ITR for dental caries management in anxious pediatric patients

Managing dental caries in children requires clinicians to weigh risks and benefits unique to the pediatric population. Drs. Beau Meyer and Jennifer Crisp explain how a new algorithm makes working through the decision-making process to plan treatment easier. They present a case study of an anxious three-year-old male whom they treat successfully using the SMART technique, which combines silver diamine fluoride with nonsurgical restorations.

Editor's note: This article first appeared in Breakthrough Clinical, the clinical specialties newsletter created just for dentists. Browse our newsletter archives to find out more and subscribe here.

DENTAL TREATMENT IN CHILDREN routinely forces the clinician to work through a decision-making process, weighing risks and benefits unique to the pediatric population. An array of factors—including age, medical and dental history, weight, extent of treatment needs, and the child’s anticipated behavior—all determine which treatment directions are most suitable. Recent highly publicized events after the use of sedation and general anesthesia for pediatric dental treatment highlight child safety issues when making these decisions, as well as shed light on caries management at the child level under a chronic disease-management framework. Even at the tooth level, advances in dental materials have pushed the caries-management paradigm from "extension for prevention" to "minimally invasive dentistry," with a renewed focus on nonsurgical techniques and the primary goal to preserve healthy tooth structure. (1)

More recently, a new article proposes an algorithm to aid clinicians when selecting between various behavior- and disease-management strategies for children with early childhood caries. (2) In today’s world of patient safety and minimally invasive dentistry, nonsurgical caries management is an essential component of the treatment repertoire for clinicians who care for children.

Nonsurgical repertoire

Interim therapeutic restorations (ITR) provide a useful approach in children with high levels of dental anxiety and those who are poor candidates for pharmacologic behavioral guidance. This technique uses gentle hand instrumentation, occasional careful slow-speed excavation, and restorations with glass ionomer, but it does not involve the use of local anesthesia. The major advantage of this technique is the avoidance of aspects that commonly solicit anxiety in pediatric patients, such as noise, vibration, and local anesthetic injections. (3)

Silver diamine fluoride (SDF) has been a hot topic in pediatric dentistry since its introduction to the United States in 2015. For years, pediatric dentists have been applying this caries-arresting medicament under the auspices of the shifting paradigm of chronic disease management and caries control before intervening to restore form and function. SDF is 66% effective at arresting caries in children, (4) and it is now being combined with ITR in a technique called the Silver Modified Atraumatic Restorative Technique (SMART). The SMART technique offers highly anxious children an interim alternative to traditional restorative techniques.

Another approach that is gaining traction in pediatric dentistry is the Hall Technique for placing stainless-steel crowns. First developed in the 1980s as a way to provide a temporary therapy for children in rural parts of the United Kingdom with poor access to definitive treatment, this technique involves no caries removal and minimal crown preparation. (5) The biological process by which caries progresses is limited by sealing off the metabolic source. A recent study in the United States found that crowns placed by the Hall Technique had a 97% success rate, comparable to the traditional preparation of stainless-steel crowns placed on primary molars. (5)

Pediatric dentistry treatment planning

In a pediatric population, behavioral guidance may limit the type of definitive treatment dental practitioners can offer their patients. For a poorly cooperative child, moderate sedation and/or general anesthesia are reasonable options for children with moderate to severe treatment needs. Though rare, these behavior guidance techniques can pose potentially life-altering risks. The emergence of patient safety as a critical component of treatment planning dictates that nonsurgical caries-management techniques be considered to circumvent some of these risks. Fortunately, as discussed above, these nonsurgical strategies can be effective in managing dental disease in children.

Pediatric case

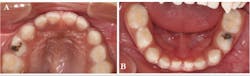

A three-year-old Hispanic male came to the clinic for his first dental visit. He was a well child without significant medical issues, and he regularly saw his pediatrician for well-child checks. The mother and patient denied any history of orofacial or dental symptoms, but mom was “concerned about a cavity in his bottom teeth.” The child was highly reactive to the dental environment and uncooperative for a knee-to-knee clinical exam. We were able to identify two carious lesions on the occlusal surfaces of the child's teeth—Nos. B and L (figure 1), but we were unable to obtain diagnostic radiographs.

Figure 1: Carious lesions noted on tooth No. B (shown in photo A) and tooth No. L (shown in photo B)

Decision-making process

We applied a systematic decision-making process to recommend treatment options to the family for the child's carious lesions. The first step was determining the etiology of the diagnosis. Once we identified the diagnosis and etiology, we created a list of restorative treatment options for the pit and fissure caries, which would include resin-modified glass ionomer, composite resin, amalgam, or full-coverage crowns (stainless steel versus preveneered stainless steel versus zirconia). The suitability of these options depends on caries risk, caregiver preferences, and technique sensitivity. In many cases, this hinges on the dentist’s ability to manage the child’s behavior effectively during treatment.

The behavior guidance plan ranges from basic techniques, such as positive reinforcement and tell-show-do, to more advanced techniques, such as moderate sedation and general anesthesia. The presence of health risk factors—such as obesity, airway abnormalities (e.g., enlarged tonsils, reactive airway, disease, etc.), developmental delay, and moderate or severe systemic disease—may preclude the use of pharmacologic management.

For this patient, key decision-making input was summarized as follows:

- Etiology: The family owns a candy store, and the child was stealing and eating candy when the mother was not looking. The family also used candy as a reward for good behavior.

- High caries risk: The primary etiologic factor was the presence of lesions and poor oral hygiene.

- Uncooperative behavior: The child was highly reactive and uncooperative.

- Health risk assessment: The child had enlarged tonsils, but otherwise no major risk factors for sedation or general anesthesia.

- Dental treatment needs: These were limited to the occlusal surfaces of two teeth.

- Family preferences: They understood the need for intervention but were highly anxious about advanced behavior-management techniques.

Following the systematic, child safety-centered algorithm (figure 2), and in consideration of the family's treatment preferences, we determined that the risks of pharmacologic behavior guidance outweighed its benefits. We knew that the child could not cooperate for conventional restorative treatment, so we offered nonsurgical caries management. The patient and family agreed. In pursuing this approach, it was essential that the family understand the importance of careful monitoring and intervention to limit disease progression.

Figure 2: This algorithm outlines a framework for selecting a behavior- and disease-management plan for young children in nonemergent situations. The algorithm should begin anew: 1. at each clinical encounter when new restorative/surgical needs are noted, and 2. if the disease is progressive or the originally selected management option fails. Note: General anesthesia in children younger than 24 months should be completed in a hospital-based setting. (2) (Reproduced with permission. Copyright © 2018 American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry)

CLICK TO VIEW DIAGRAM LARGER

We applied SDF (Advantage Arrest, Elevate Oral Care LLC) and resin-modified glass ionomer (Fuji II LC, GC America Inc.) temporary restorations to the carious lesions on teeth Nos. B and L, and continued to monitor them at three-month intervals. After one year of follow-up, the restorations were intact, and the family had made dramatic improvements in controlling the primary etiologic factor (figure 3). After two years of follow-up, the temporary restoration on tooth No. L fell out and required replacement (figure 4).

Figure 3: SDF plus resin-modified glass ionomer was placed on teeth Nos. B and L using the SMART technique. Restorations were intact 12 months later (tooth No. B shown in photo A, and tooth No. L shown in photo B).

Figure 4: Radiographs at 24 months showed an intact SMART restoration on the occlusal of tooth No. B (photo A) and minimal, if any, progression of the lesion on tooth No. L (photo B). The temporary SMART restoration was missing from the cavitated lesion on tooth No. L (photo C). A stainless-steel crown was placed over tooth No. L using the Hall Technique (photo D).

The lesion was stable and had not progressed, but the cavity served as a food trap. Rather than replace the failed temporary, we recommended placing a definitive restoration—in this case, a stainless-steel crown based on the child’s caries risk. Since the child was still a highly anxious patient, we used the Hall Technique. We applied topical anesthesia to the gingiva, verified the size of the crown, and cemented the crown with glass ionomer cement (Ketac Cem, 3M ESPE). The occlusion was high upon dismissal from the clinic, but it normalized by the time the patient returned for his follow-up visit one month later. This child’s dental disease has been managed very well under the chronic disease-management framework.

Summary

Conventional restorative dentistry is still an important part of our everyday pediatric dentistry practice. However, the growing importance of patient safety and the shift toward minimally invasive dentistry have tested the traditional treatment-planning paradigms for children. We perform nonsurgical techniques only if the individual situation dictates doing so, which applies to approximately 15% of our practice’s patients who have dental caries. We have found success in applying the systematic algorithm described in this article, and—as shown in this case study—we effectively managed a child's dental disease and mitigated any safety risks.

Author's note: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

1. Frencken JE, Peters MC, Manton DJ, Leal SC, Gordan VV, Eden E. Minimal intervention dentistry for managing dental caries—a review: report of a FDI task group. Int Dent J. 2012;62(5):223-243. doi:10.1111/idj.12007.

2. Meyer BD, Lee JY, Thikkurissy S, Casamassimo PS, Vann WF Jr. An algorithm-based approach for behavior and disease management in children. Pediatr Dent. 2018;40(2):89-92. Also available at http://www.aapd.org/.

3. Duangthip D, Chen KJ, Gao SS, Lo ECM, Chu CH. Managing early childhood caries with atraumatic restorative treatment and topical silver and fluoride agents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(10). doi:10.3390/ijerph14101204.

4. Chibinski AC, Wambier LM, Feltrin J, Loguercio AD, Wambier DS, Reis A. Silver diamine fluoride has efficacy in controlling caries progression in primary teeth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Caries Res. 2017;51(5):527-541. doi:10.1159/000478668.

5. Ludwig KH, Fontana M, Vinson LA, Platt JA, Dean JA. The success of stainless steel crowns placed with the Hall technique: a retrospective study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145(12):1248-1253. doi:10.14219/jada.2014.89.

Editor's note: This article first appeared in Breakthrough Clinical, the clinical specialties newsletter created just for dentists. Browse our newsletter archives to find out more and subscribe here.