Recognizing and treating compromised dental function

Dr. Neeraj Khanna's clinical case began with a frustrated patient, who endured many failed attempts to repair a functional problem, and was solved using the principles of occlusion and function. Learn how he created a predictable treatment plan using mounted models (in centric relation), respecting the patient’s desires, goals, and limited budget.

Editor's note: This article first appeared in DE's Breakthrough Clinical with Stacey Simmons, DDS. Find out more about it and subscribe here.

Many patients have occlusal problems that are related to function. Examples include failing restorations due to wear or fracture; joint, muscle, or tooth pain; and other signs of instability. Recognizing compromised function requires an understanding of the principles of function as they relate to the masticatory system. This system is comprised of three basic parts:

- Temporomandibular joints (TMJ)

- Muscles of mastication

- Dentition including occlusion (the relationship of how the upper and lower teeth relate to each other during functional movements (1)

A lack of complete understanding of the interrelationships of these principles will lead to frustration for both the dentist and the patient. One common scenario occurs after a crown preparation on a second molar is completed and the dentist notices that there is inadequate interocclusal space during fabrication of the provisional restoration. The dentist either makes a provisional restoration that is very thin or removes more tooth structure. As a result, the final restoration requires extensive occlusal adjustments, and—in most cases—the anatomy of the restoration is removed and the final crown is weakened.

This article will review a patient’s case with a very different functional problem that was solved predictably using the principles of occlusion and function. These principles are founded on the understanding that the temporomandibular joints, muscles of mastication, and the position and shape of the dentition are all working in harmony with each other. (2) This approach to treatment allows the clinician to provide the most conservative treatment possible while improving the patient’s occlusion and function. In this specific case, a predictable treatment plan was created using mounted models (in centric relation) and respecting the patient’s desires, goals, and limited budget.

Patient summary

This clinical case began with a frustrated 75-year-old patient, who, after many years of failed attempts to repair the functional problem, came to the realization that a different solution was in order. The existing problem of an upper removable precision attachment partial denture was addressed first. The issue at hand was that the partial denture was perforated at the precision attachments, with the upper left side being more significant compared to the right side (figures 1–5). As a result, retention was adequate on the right side, but limited on the left. The patient was also concerned about esthetics, but needed a solution that kept a restricted budget in mind.

Upon completion of a complete examination, the following was noted:

TMJ: Normal. No clicking or popping, range of motion normal, no deviation of the mandible during opening or closing.

Muscles: Palpation normal, except for mild tenderness noted on both lateral and medial pterygoid muscles.

Joint loading: Both joints could be fully loaded with no tension or tenderness. First point of contact in centric relation was upper right canine/bicuspid with an anterior left slide into maximum intercuspation.

Occlusion: Localized wear noted on the lower anterior teeth, especially on teeth Nos. 22 and 23. Upper and lower planes of occlusion are not compatible for ideal function and esthetics.

Dentition: Upper anterior splinted crowns had open margins and caries. Radiographs confirm decay, along with open margins (figures 6–11). Lower incisal anterior wear noted (figure 2).

Periodontium: Probing depths normal on all teeth, with some bleeding noted around the margins of the upper splinted crowns. Slight to moderate bone loss on lower anterior teeth.

The occlusion needed to be changed to a more desirable one, as well as improve the esthetics. After examining all of the findings, options were presented to the patient for the final restorative outcome. Because of a limited budget, the patient preferred to have the remaining maxillary teeth removed and an immediate maxillary denture placed. As a result, a new plane of occlusion needed to be predictably determined and clearly communicated to the laboratory technician.

The treatment-planning process

The treatment planning process began by using photography to evaluate the current position of the maxillary anterior teeth both vertically and horizontally. Specifically, three photographs were used to verify these two dimensions.

Figure 12 illustrates the horizontal position of the maxillary anterior teeth to the lower lip. The goal of this photo is to see the incisal edge just inside the lower lip line. (3) With this patient, it was clear that the horizontal position was placed too far facially.

Keep in mind that some patients exhibit a skeletal Class II or III, and in such patients a happy medium will need to be established where the horizontal position may be changed.

The vertical position of the incisal edge for this particular patient was verified using two photos: the repose or rest position and the “E” or exaggerated smile photo. Both of these photographs provide valuable information regarding the vertical position of the maxillary incisal edge.

At rest or repose, ideally 1 mm to 3 mm of incisal edge is revealed. Often, aging causes the upper lip to drop, which reveals less than the 1 mm to 3 mm of incisal edge. (4) This patient does show some reveal, as illustrated in Figure 13, but at her age, none is expected to be seen. However, to confirm this, the “E” smile photo was used. This photo illustrates where the incisal edge falls between the upper and lower lips. Figure 14 illustrates how to use this photograph to help determine the vertical position of the incisal edge. Ideally, the incisal edge should be somewhere between 50% and 70% of the distance between the upper and lower lip. (5)

Using Figures 12, 13, and 14, it was concluded that the current incisal edge position was incorrect both vertically and horizontally. The goal of treatment was to shorten the incisal edge vertically and bring it lingually for horizontal correction.

In addition, the correct length of the central incisor was calculated by using the ideal length-to-width ratio tool found in the Dawson Wizard Software (figure 15). As a result, this change could be transferred to the mounted models (figures 16 and 17). This new vertical and horizontal position of the central incisor provided a guide for the upper occlusal plane. Once the upper occlusal plane was established, re-creating the lower plan became more simplified.

Figure 15

These modifications led to the following treatment plan:

- Conservatively reshape teeth Nos. 24 through 27 and composite bond teeth Nos. 22 and 23

- Porcelain-fused-to-metal crown No. 20 (to be used with existing partial denture)

- Replace existing lower partial denture with new posterior teeth

- Extract remaining upper anterior teeth with delivery of immediate denture

- Deliver rebased existing lower partial denture with new denture teeth and equilibrate occlusion

- Reline immediate upper denture in several months

Tips for communicating with technicians and specialists

The best way to communicate with technicians is to give them with as much information as possible. In addition, letting them understand the goals (both the dentist’s and patient’s) and treatment objectives minimizes the risk of miscommunication. The most important element is the end result, and it is up to the dentist to have the confidence to delegate expectations to whomever is involved (lab technicians, specialists, and others) to help achieve the best results for the patients.

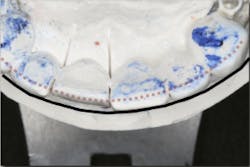

In this case, the diagnostic wax-up of the mounted models gave the technician the new position of the upper incisal edge. The technician then set the maxillary teeth appropriately using models and additional photographs. At the same time, tooth No. 20 was restored, but the lab technician kept the crown and lower partial to predictably create the lower occlusal plane and easily articulate this with the upper immediate denture (figure 18). Note the improved curve of Spee in Figures 19 and 20. Upon completion of the prosthesis, treatment was completed as outlined and the results made the patient feel very comfortable functionally, esthetically, and phonetically.

Figure 18

There was some fine-tuning to the patient's occlusion during the healing period. Nevertheless, the goals of treatment were accomplished very predictably. Figures 21 (horizontal position) and 22 (vertical position) verify both the new vertical and horizontal positions of the upper incisal edge.

Final thoughts

Understanding the patient’s masticatory system requires the dentist to gather the correct data through a comprehensive examination. (6) In addition, diagnostic records (mounted models in centric relation and digital photography) can be used to provide predictable results. The overall esthetic outcome, along with improved function, gave the patient a new outlook on life and increased confidence—all within her budget (figures 23–25). The Dawson Academy is a great resource for learning about the masticatory system, functional esthetics, and a predictable treatment-planning protocol.

References

1. Clark JR, Evans RD. Functional occlusion I. A review. J Orthod. 2001;28(1):76-81.

2. Dawson PE. Functional Occlusion: From TMJ to Smile Design. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Inc.; 2007.

3. Passia N, Blatz M, Strub JR. Is the smile line a valid parameter for esthetic evaluation? A systematic literature review. Eur J Esthet Dent. 2011;6(3):314-327.

4. Vig RG, Brundo GC. The kinetics of anterior tooth display. J Prosthet Dent. 1978;39(5):502-504.

5. Pound E. Utilizing speech to simplify a denture service. J Prosthet Dent. 2006;95(1):1-9.

6. Khanna N. The art of the complete examination—part 1. J Ont Dent Assoc. 2011;95(7):36-39.

Editor's note: This article first appeared in DE's Breakthrough Clinical with Stacey Simmons, DDS. Find out more about it and subscribe here.